The office market transformation and how it will impact cities

As the world moves beyond COVID-19, cities are impacted by the “work from home” transformation and other workplace changes. Many questions remain about how cities will function and adjust to a new workplace “normal.” The rapidly shifting office environment affects some of the most important North American urban areas, where millions live and work. Adversity breeds invention and ultimately, a repositioning of accepted conditions. Potential changes are emerging based on past trends and recent activity, showing how they may alter our overall lifestyle.

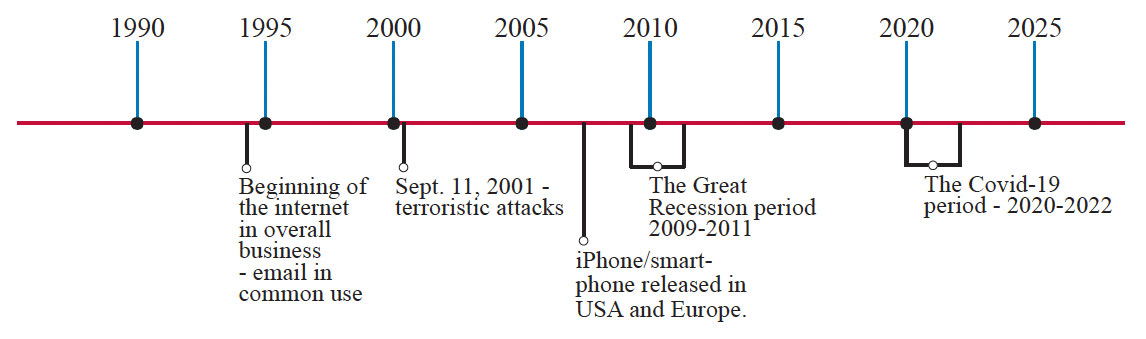

Related to office trends, building typology has been evolving for more than two decades. Many positive and tragic events have converged over a relatively short period of time, altering our world.

The September 11, 2001, attacks affected office users. Two significant sites were dramatically impacted—the New York World Trade Center and the Pentagon building in DC. The aftermath included a push to rethink the location of companies, how offices should be situated, and whether cities were logical places to have offices versus suburbs. Density and the building height concerned many company leaders and employees, as did the potential need to separate departments and modify office and corporate structure. In short, the work environment in place for many decades was challenged.

In the late 2000s, the iPhone was introduced, followed by the widespread adoption of the digital pad, which brought a paradigm shift in technology. Also, more powerful laptops allowed the “office” to become any place with reasonably strong Internet access. (That change also depended on earlier breakthroughs, going back to the 1990s, of broadband access, and electronic communications becoming standard in business.)

As workplace options expanded, the Great Recession of 2009-2011 disrupted the economy and pushed companies to reevaluate long-term revenues, often resulting in cutting overhead costs—specifically, office needs.

This led to reevaluating office layouts and how much space was needed for each worker. This led to a rise in communal workspaces, working in groups, more casual environments, and fewer designated private offices. This moved companies to minimize office footprints, allowing more people to work in smaller spaces. The square footage per worker went down, reversing a long-term trend. By the late 2000s companies had already accepted and encouraged concepts like “hoteling,” whereby workers dynamically schedule their use of communal workspaces. The work-from-home model began to take root, and some companies allowed employees to work out of the office for one or two days a week.

These changes over three decades spurred the evolution of office buildings and work norms. Then came COVID.

Work-from-home and office rethinking

The downtown office market received another setback in COVID. Many governmental bodies and companies increased online and virtual business environments. Questions remain about how these shifts will change workplaces, and for how long. However, signs indicate where this is going. Historically, North American cities had downtown districts that were single-use with a high percentage of office buildings and other uses oriented to support the office market. The service industry, food, and other retail primarily supported the office employees.

The result was a Central Business District (CBD), utilized mainly for 40 hours a week, 9 am to 5 pm, during the 5-day work week. These districts were often dead areas during evenings and throughout the weekends. In recent years, city leaders and planners have advocated for alternative uses to create mixed-use districts that would lead to activity throughout the week—the “24-hour city.” When these mixed-use transformations were implemented, many districts changed dramatically. COVID promoted this concept in CBDs of most cities, driven by a need to convert underutilized office space.

Physical characteristics of office buildings

While converting office space to residential and other uses has become a big trend in recent years, this redevelopment has been underway for many decades. Many excellent examples can be studied.

The overall footprint of the floor plan—the perimeter and size of each floor—is a primary consideration. Deep floor plates and limited perimeter walls can make or break the potential for an office conversion. Other important issues include exterior materials, window types, mechanical, electrical, plumbing systems, and life safety details. Also, construction types, floors, and load capacity may impact conversion potential. Not all office buildings lend themselves to residential conversion. Alternatively, a variety of other use conversions are possible. Demolition and site reuse is another option. This allows for reuse flexibility if site clearance can be incorporated into the redevelopment budget.

Office buildings vary dramatically. They include vertically oriented older towers with smaller floor plates and horizontal buildings that spread out over the landscape with larger floor plates. Locations, context, and adjacencies are critical; a structure that is part of a walkable, mixed-use district differs dramatically from an office building surrounded by parking and disconnected from other buildings. A thorough analysis is needed to identify conversion potential, using a set of criteria to make a “go or no go” decision.

Here is how one team approached the office conversion process in 2021. Gensler created criteria and a checklist for the adaptive reuse of a 12-story, 1968 office tower in the Midtown district of Toronto. The team analyzed physical conditions to determine the feasibility of demolition and the site's value as a redevelopment. They developed a “conversion calculator” and applied it to a point scale. Weighted issues included site context, building form, floor plate, envelope, and servicing. These points, and a few others, are being used by architects and development teams to assist in identifying the true possibility of converting office structures. Many cities have studied their office building stock in recent years and announced repurposed structure projects likely to dramatically alter cityscapes.

“Move to Quality” and other site adjacencies

“Move to Quality” is an increasingly popular strategy. The demand for higher-quality office space is rising as users reevaluate their needs—specifically, the business space needed given the incorporation of “work from home” and virtual offices. An office user can reevaluate space needs and look for a new, smaller location. With smaller space needs, higher-quality office space is economically feasible.

The office user reconsiders both the quality of the building and the value of the location, including adjacent amenities. “Move to Quality” often means relocating to a downtown or mixed-use district with restaurants, parks, and other amenities within walking distance. These walkable places are the opposite of suburban office parks that experience higher vacancies and less demand.

Detroit was at the forefront of converting office buildings to alternative uses. Over the past three decades, dozens of office-to-residential conversions have occurred in the city’s downtown. These projects are varied—small to large, old and newer, as large as 600-foot-high skyscrapers. Currently, some are under construction, and more are planned.

Over the years, my firm, Archive DS, has worked on several adaptive reuse projects, including the century-old, 12-story Vinton Building, the multi-structure Merchants Row redevelopment, the 8-story 1 John R Street building, and the Baltimore Station redevelopment. Archive DS has had various roles, from initial analysis of existing conditions, capacity studies of the structures, identifying fundamental building systems, branding the projects for the proposed residential use, architectural construction drawing, and implementation. These buildings are nearly a century old, making them a challenge on many levels. However, they were ultimately successfully completed, and are now contributing to the urban context and enhancing the overall city.

Detroit has benefited in many ways. For example, iconic architecture has been repositioned for future generations. Additionally, the downtown has gained from increased residential activity. The buildings have strong adjacencies and efficient floor-plan configurations, among other characteristics. In Detroit, these factors have generally led to former office structures being appropriate for adaptive reuse. However, challenges to office conversions include the need for physical improvements such as masonry work, window restoration, and vertical circulation upgrades. Additionally, internal floor plans and the utility conditions often needed reworking. Other fundamental difficulties arose, like the lack of on-site parking and limits to creating certain amenities that are tough to integrate into older historic buildings.

Many cities have embraced office conversions

Many cities have promoted office building conversion. The historic Manhattan downtown district is a notable example. The Wall Street financial district had been essentially office use only, with primarily weekday-only activity, since the 1920s. However, in the mid-1990s, New York City created an incentive program to alter the after-hours ghost town of Lower Manhattan into a 24-hour multi-use neighborhood. The Lower Manhattan Conversion Program 91995-2006, a.k.a 421-g Tax Incentive, offered tax abatements and additional incentives to promote office building to residential use conversions. This had a significant impact, as tall historic skyscrapers with small plates, primarily built in the 1920s, were converted into residential.

Around that same time, in the early 1990s, Toronto started to push for change within the downtown financial district and adjacent office areas. Mayor Barbara Hall and city planning leaders explored rezoning to encourage residential uses. One result was the redevelopment of the 1961 National Trust building. This project, named the Metropole, was one of the first in Toronto, completed in 1997. It included ground floor retail uses and residential above. Its intact and sound concrete structure made the building a good candidate for conversion. Among the assets were an efficient floor plate for the layout of residential units, interior parking with three underground and two above-ground levels, and an exceptional location between the financial hub of Canada and the historic St. Lawrence market district. A streetcar and subway stop were located within steps of the entrance. The building’s key elements could guide what is needed for the adaptive reuse of such a structure. The Metropole is a good precedent for this project type, and its impact on the adjacent district was significant.

Even though office conversions have tended toward residential uses, many other alternative uses have worked well. These precedents prove that office buildings can be successfully converted into numerous uses that enhance cities. Increasingly, cities and developers are exploring out-of-the-box ways to use vacant or underproducing office buildings. These uses include breweries, spas, vertical growing farms, storage centers, schools, and daycares, with more uses continuing to be considered. Many office buildings targeted for conversion benefit from assets like a good location, intact and functioning building systems, efficient configurations, quality of materials, and more. With these fundamental elements in place, the possibility of conversion is high.

The impact of office conversions

Office conversions have had a positive impact on many cities. Manhattan's financial district has become a true, mixed-use neighborhood. After decades of mostly single use, the tip of Manhattan has become a 24-hour, 7-day-a-week neighborhood. With an emphasis on office-to-residential building conversions, implemented over several decades, the population, services, and amenities have grown. Additionally, the incredible architecture of century-old skyscrapers that have graced this iconic skyline since the 1920s has been repurposed. The program, initiated by the city and embraced by the developers to save many struggling and antiquated office structures, has become a precedent strategy for other cities regarding adaptive reuse.

Downtown Detroit was formerly a commerce center focused on retail, shopping, services, and offices. Downtown has had dozens of office-to-residential conversions, often including ground-floor retail, mostly of historic structures. These buildings generally range from 10 to 40 stories. This has created a neighborhood where pedestrians are active daily and well into the evening. People walk dogs, eat at outdoor cafes, sit in parks, and support retail. New retailers accommodate these residents as pet shops, markets, and support businesses grace the ground floor of historic structures.

The Metropole building has catalyzed office-to-residential conversions in Toronto. Until this project was completed, the district was a CBD. The 24-story Metropole added over 300 residential units to the district. That equates to approximately 500 new residents. The influence of this building was immediately evident in the street activity nearby—from the retail spaces to a small public park a block away. New restaurants and cafes opened in nearby buildings. Within a short time of the opening of the Metropole, additional office-to-residential conversions in the financial district zones were launched.

Currently, many cities are experiencing the conversion of office structures to alternative uses. Whether individual projects or municipal programs promoting adaptive reuse, a transformation is underway in many cities. From Chicago to Denver, New Orleans to Cincinnati, the “monoculture of offices” is changing. How are these conversions making cities better?

Office transformations make cities dynamic

Can our cities become better places for people even after the removal of office space downtown? One example is the strengthening of mixed-use over single-use districts. Historically, supporting commercial spaces were typically open during standard office hours. Conversion to residential increases the need for retail users, restaurants, markets, and services while establishing an elongated period of activity.

Great cities, neighborhoods, downtowns, and urban districts are more successful and sought after if they are active, mixed-use environments. With the decline in office space demand, single-use buildings quickly become candidates for adaptive reuse. The transformational potential of these structures into civic assets is significant.

Many city leaders and property owners are reasonably concerned that the decline of office use in cities may become a real estate burden. There are many unknowns regarding where the office transition circumstance will end up. However, as office buildings are transformed, repositioned, reworked, or reestablished, more creative, prosperous, and effective structures in our cities will likely result, and our cities will greatly benefit.