Sustainable urbanism at a glance

Nico Larco, professor of architecture and urban design at the University of Oregon and director of the Urbanism Next Center, presented the Sustainable Urban Design Handbook on On the Park Bench this week. Ten years in the making, the Handbook published by Routledge this year is organized around the Sustainable Urban Design Framework, a table shown above.

The Handbook, co-authored by Larco and Kaarin Knudson, offers a comprehensive approach to what makes a place sustainable, and how communities can pursue place-based sustainability. Larco explains: “There is a lot of fantastic work in different disciplines that addresses these questions. The problem has been that that work is often siloed—and does not address the impacts one element of urban design has on another element.”

In Larco’s framework, new urbanists will recognize the scales of the Charter of the New Urbanism. The table is organized into actions and policies on the regional, neighborhood, and block/street scale. Larco adds the project/parcel scale, which he explains is the private sector component of the public sector block and street (the Charter combines public and private sector in the block/street/building scale). In other words, the framework is nearly exactly analogous to the Charter in how it treats scale. As Larco explains:

“There has been a lot of great work coming out of the CNU movement that directly impacted the thinking behind the Sustainable Urban Design Framework and the book. You will see direct and indirect references in the book to the Sprawl Repair Manual, the Smart Growth Manual, Smart Code, and Retrofitting Suburbia, among others. If you are trying to comprehensively understand sustainability in urban design, you have to understand that there are fundamentally different structures and criteria that exist at different scales—and that these scales are all reliant on each other.”

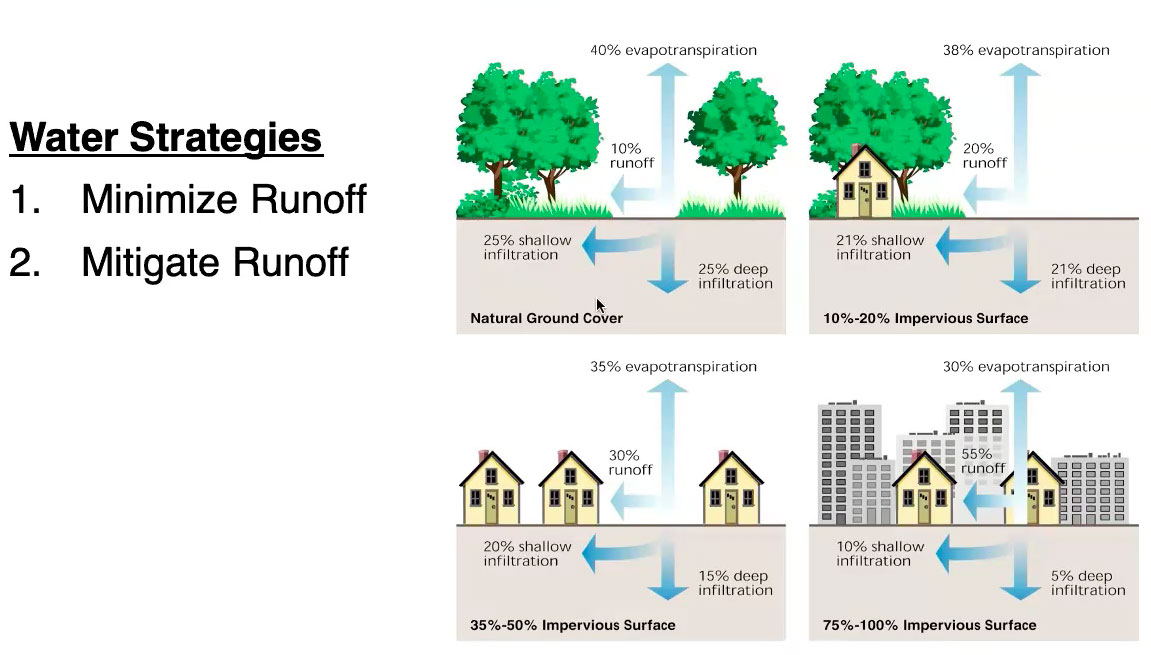

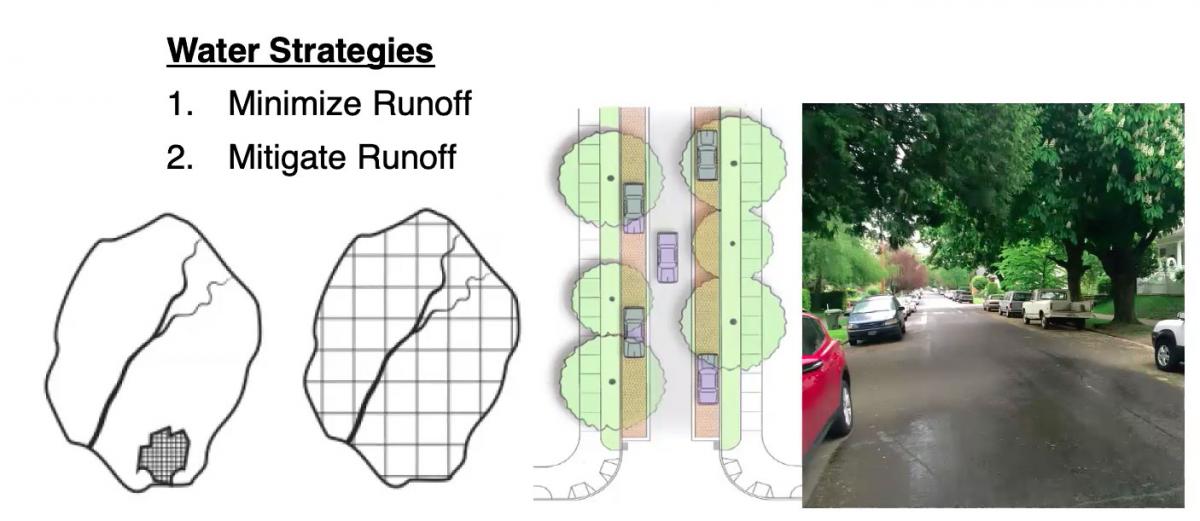

Most of the resources Larco mentions apply the Rural-to-Urban Transect, and that idea seems to be embedded in parts of the Handbook. For example, stormwater behaves much differently in rural versus urban places, so how it is treated must vary. Here’s one of the slides from his presentation showing stormwater in different Transect locations.

The highly urban locations demonstrate many benefits, particularly if you look at the framework rows for energy use & greenhouse gas, and equity & health. So how can planners compensate for the water disadvantages in the more urban locations? Two answers are compact urban development and trees—a robust urban canopy.

In addition to columns representing scales of urbanism, the framework has five rows, which include water, ecology & habitat, and energy use & production, in addition to the rows already mentioned. The framework is clever in that it allows, at a glance, connections to be made among complex urban policies and physical forms while showing how they relate to one another.

“A walkable, complete street is good, but it really becomes great when it is tied into a robust multimodal network at the regional scale,” he explains. “Transit cannot exist without density at the neighborhood scale. Ecological buffers are most effective when they are tied into a larger ecological network. These things are all related and we need to understand that so that we can be most effective in pushing for more sustainable solutions at the scale we are working in, while advocating for changes, helping create regulations, and/or developing partnerships with other entities that are working at scales we may not control.”

To gather all of these ideas and information on a single table that reveals urbanism relationships is quite an achievement. Larco sees uses for this in coding, comprehensive planning, specific projects, education, and public process.

“My hope is that this work is helpful as a design tool (helping designers and planners understand what they should be paying attention to and the relationship between different urban design elements), as an evaluation tool (to help understand the existing context, what is working, what is low-hanging fruit, and what is going to require more work and partnerships), and as a stakeholder engagement tool (to help communities prioritize their outcome goals, and understand how those goals translate into actual physical urban design elements). As was asked in the webinar – I LOVE the idea of this framework helping organize regulation and helping point to gaps or discrepancies in regulation that impede specific urban design elements that are needed to get to desired outcomes. I am also hopeful that this will help orient students and professionals about the breadth of topics we should be thinking about in sustainable urban design.”

See the whole webinar here.