Four steps to affordable housing

Four steps lead to building affordable housing outside of pure subsidy, Fernando Pages Ruiz argues. These are:

- Design for affordability

- Collaborate towards affordability

- Build affordably

- Use new land strategies that are becoming more available to cut land costs

Fernando, who presented to CNU’s On the Park Bench, is critical of what he calls “cheap-washing,” which he defines as claiming affordability based on proximity to transit or other benefits—like improved health from walking. These characteristics are good, but they don’t make a home affordable.

Key aspects of affordable construction

The first three steps deal with construction issues such as efficient framing, massing, foundations, siding, roofs, and the organization of mechanical systems and utilities in a house. They also involve window, garage, paving, and interior finish options, some of which Fernando explained in the webinar.

However, land strategies that employ recent regulatory shifts and new urban designs are important, particularly in metro areas with high land costs. Developers can provide genuine affordability through construction “trade secrets” and land strategies. Fernando, an author and builder, offers a few examples.

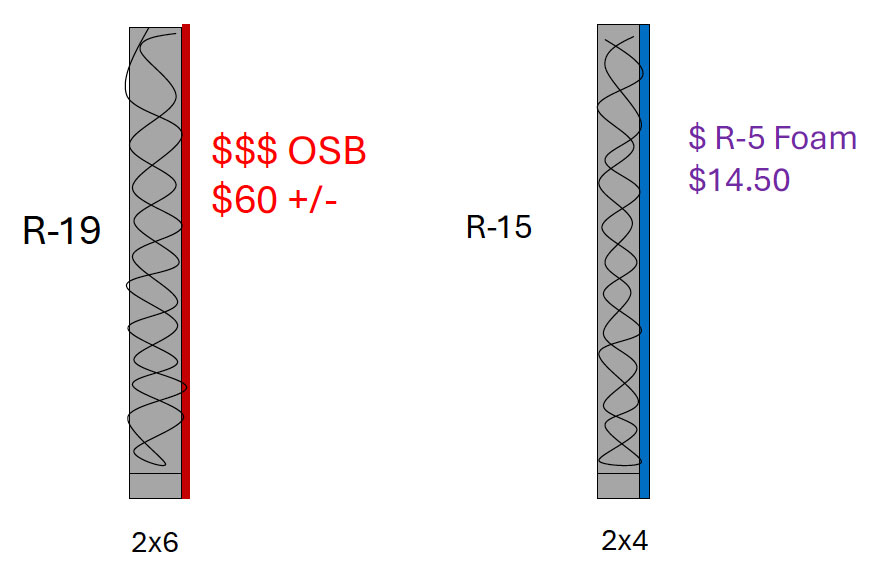

A typical outside wall uses 2-by-6 studs, a layer of oriented strand board (OSB), and R-19 insulation between the studs. The OSB costs $60/linear foot. Fernando uses a 2-by-4 wall, sheathed in an insulating foam board instead of OSB, providing better insulation. The lost strength is provided by half-inch-thick drywall, nailed every 7 inches instead of the usual 16 inches. Replacing OSB with foam board will save $4,000 on a typical house, he explains. Most builders and architects are unaware of this option in the code. The “codes are becoming more complicated, because they have more options. In the options, you find affordability,” he says.

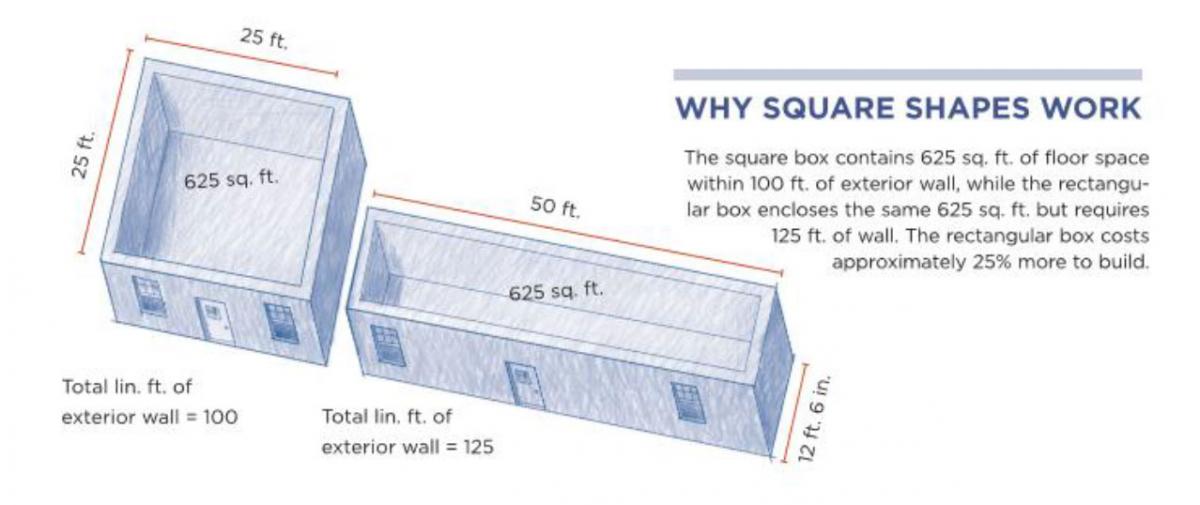

Another trick is calculating the ratio of floor space to exterior wall, which is determined by the massing. This number should be as close to the ideal of 1:1 as possible, often achieved by a shape such as 34 feet by 24 feet, a favorite dimension (and also one commonly used in the postwar period, the heyday of affordable housing). A good ratio reduces materials substantially. “I am assured just by getting a good floor-to-wall ratio that I am designing and building an affordable house,” he explains.

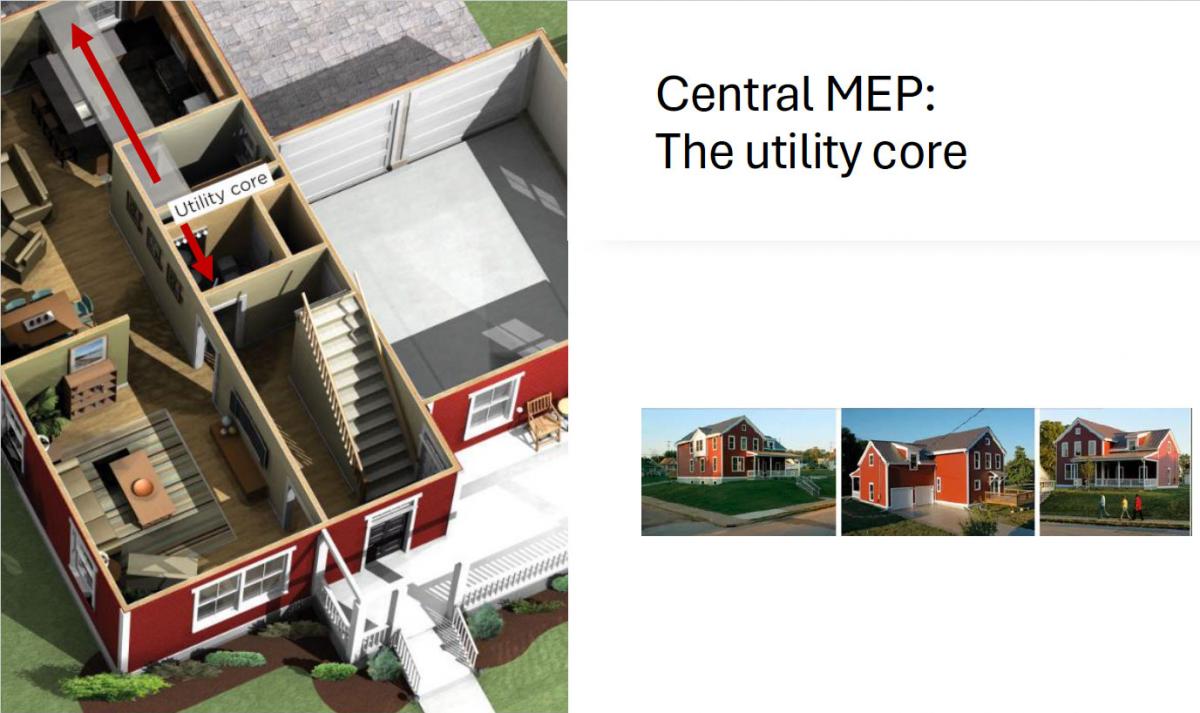

Utility and mechanical systems must be centralized. Fernando aims for a “wet-room rectangle, a distinct area of the house where the plumbing is contained.” Minimizing utilities is green, because it reduces the resources used to build the house. “This is the kind of discipline you have to have to build an affordable house. ‘Green houses’ start at half a million. You can actually build a house for under $100,000 if you focus on all of the things I am talking about.”

To minimize labor and materials, good collaboration with sub-contractors is a must, Fernando says—starting with the most expensive trades like plumbers, electricians, and HVAC. “They think in terms of rules of thumb. You have to convince them to think in terms of minimizing the materials and labor. So you have to find people to collaborate with and get them on board,” he says.

An all-electric home, which is inexpensive, can also offer low utility bills with good insulation and caulking, both of which are cheap and green. “I do cheap things, so I can do other cheap things,” he explains succinctly.

Builders can also use advanced framing, a lumber-sparing approach. This involves spacing studs further out and not using the same header throughout the house (use only the lumber that is required over doors and windows). Foundations are another potential gold mine of savings. But cutting costs requires good quality control. “If you are going to use minumum lumber and minimum concrete, you better make sure that lumber is in the right place, and the concrete is poured in the right conditions,” he says. Otherwise, warranty costs will eat your lunch.

New land strategies

Laws across the US are changing, enabling strategies to reduce land costs in infill development. He says eighteen current legislative bills incentivize ADUs and multiple residences on single-family lots. This is where new urban design comes in.

The Tealight Series, designed by Pel-Ona in Denver, consists of houses on 32-by-55-foot lots, three of which fit side-by-side on a city lot (see photo at top of article). The houses run perpendicular to the sidewalk, with small shared courts in front. Each gets a small private space in the 10-foot area between the houses. Each house has an exclusive use easement with the house next door. Homeowners can build a deck for a private patio.

“It used to be that the land costs (in a place like Denver) make it impossible to do affordable housing, but with all of the new development codes, it is easier to get a really inexpensive lot. If the lot is $200,000 and you divide it in three, you get a pretty reasonable land value.”

Fernando says the garages face a common driveway in the back of the Tealight houses, which saves 40 percent on the per-unit concrete.

The Charter-Award-winning Finley Street Cottages in Atlanta by Kronberg Urbanists + Architects is another good example. The cute cottages use cost-saving construction like low rooflines and simple, inexpensive trim, siding, and foundations. Kronberg fits 14 living spaces on two lots (including renovating the original houses into duplexes). Despite the cost-saving construction, the project is very pretty.

Fernando covered the idea of pre-fab houses, which generally don’t save money—because they are so expensive to ship. But he is working on one promising application with DPZ CoDesign—just build the kitchen and bathrooms in a pre-fab module. Equipment and ductwork that serves the other living areas are spaced over the kitchen.

The most expensive house parts—the tiling, cabinets, countertops, the heart of the mechanical systems—are built in an efficient factory setting. “Then you just build the house around it. You ship only that part which makes sense to build in a factory,” Fernando explains.

Fernando recently wrote the Second Edition of Building an Affordable House: Trade Secrets to High-Value, Low-Cost Construction, published by Taunton Press. This book is a remarkable resource on building affordably—whether you are a private or public sector builder. Housing costs have risen by 40 percent in recent years at the same time that interest rates have soared, Fernando says.

Fernando explains that Frank Lloyd Wright put all of his considerable genius into affordability while maintaining high aesthetic values in his Usonian houses. He employed innovative techniques, such as shallow, frost-protected foundations that saved money. (That technique, which has worked for nine decades in Wisconsin, can still be employed today.) The great architect focused on both visible and invisible aspects of the house.

Like Frank Lloyd Wright, urbanists must pay attention to the details of construction to deliver affordability. It’s a moral imperative. See the whole video: