The housing shortage and structural costs of sprawl

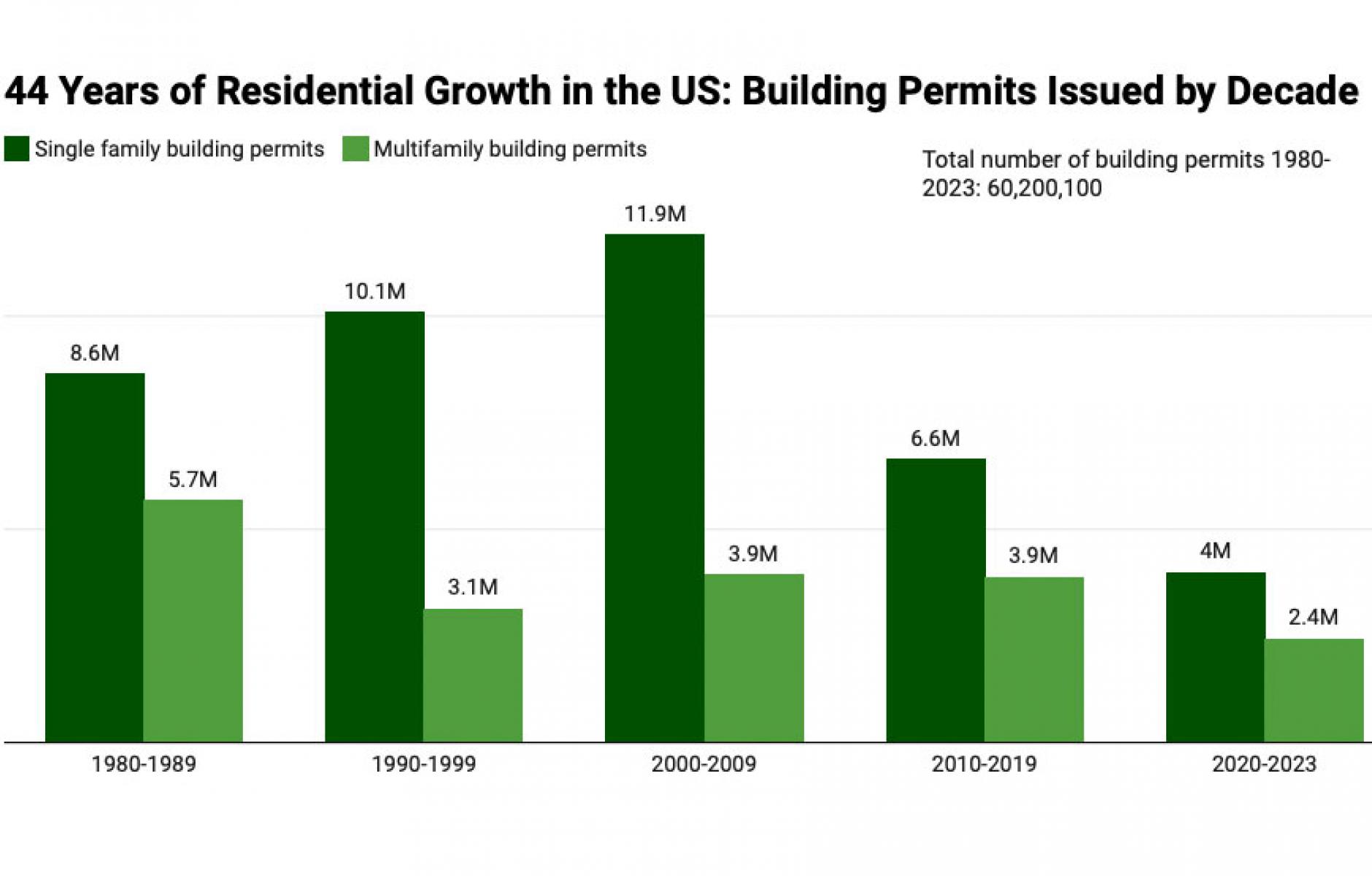

This graph shows why housing is getting so expensive. Annual housing production in the US plummeted in the 2010s, with annual single-family construction just over half of what it was in the 2000s, according to a report Top Cities for Real Estate Development. Although multifamily held its ground in the 2010s, it didn’t make up the difference.

That has left the US with a deficit of millions of homes. This report puts the deficit at 3.2 million homes, although Zillow estimates 4.5 million. The good news is that total housing construction this decade is back up to 2000s levels—but that’s not enough to close the deficit anytime soon (the graph for the 2020s shows four years at 1.6 million housing units annually).

However, solving the housing affordability crisis is not just about numbers but also location and housing type. We are now in the eighth decade of sprawl in America, and that has vastly changed the housing cost equation.

Despite some success of urbanists over the last three decades, we are still largely building housing in single-family subdivisions and large multifamily buildings. After nearly 75 years of sprawl, every city has an extensive ring of automobile-oriented suburbia. New single houses are mostly built in far-flung locations—imposing a high transportation cost on families. Plus, this development gobbles up a lot of land, and infrastructure and utility costs are high. The multifamily is often built in urban locations with lower transportation costs, but the construction costs are high, including elevators and structured parking.

Missing middle housing is hard to build at the scale needed to bring down prices. Regulatory barriers compound that situation—zoning was mostly designed to create sprawl. We can get better at missing middle development. Yet, after three or four generations of sprawl, the land-use system is costly—both economically and environmentally.

Contrast our current system with how the nation built housing up to 1950. Up to that point, walkable urbanism grew in two ways. One was infill development, which is similar to today. The other way was to extend the street grid outward. This resulted in new walkable neighborhoods—often streetcar suburbs, connected to the old urbanism.

Those neighborhoods were built on grids that were—and remain—efficient and flexible. They accommodated single-family houses and a wide range of missing middle and mixed-use properties in a mix that could shift with market demand. Extended street grids didn’t impose high transportation, land, or infrastructure costs. Lots were relatively small, and varied housing types allowed for more affordable housing.

To make housing affordable again in the long run, we must return to building new housing on efficient, simple street grids. This will not be easy, but it can be done. It will require the cooperation of traffic engineers, who have so far resisted change. However, I am encouraged by plans such as California Forever, Utah City, Daybreak, and Bastrop.

Getting back to the real estate report, the leading cities in single-family construction include Fort Worth, Houston, Jacksonville, San Antonio, Phoenix, Oklahoma City, Nashville, Austin, and Cape Coral (Florida). These are all Sunbelt cities with a ton of sprawl. Houston, San Antonio, Austin, Nashville, and Phoenix also make the top 10 in multifamily construction.

Another prominent finding is that retail and office construction has fallen off a cliff in the last four decades. Retail construction is down 89 percent, and office construction has dropped 69 percent since the 1980s. Those illustrate structural changes in our economy and lives. Everyone used to leave home to go to work and get stuff. Now, many of us can do these things from home.

All of the retail we built in the 1980s and 1990s presents an opportunity for redevelopment into multifamily and townhouses, which could be connected to transit. Peter Calthorpe argues that this is the solution to the housing crisis. In this decade, he may be right. In the long term, when most of the current traffic engineers retire, I expect we will increasingly return to building new, simple street grids—because they offer so many advantages.