How in-city highways impact social lives and health

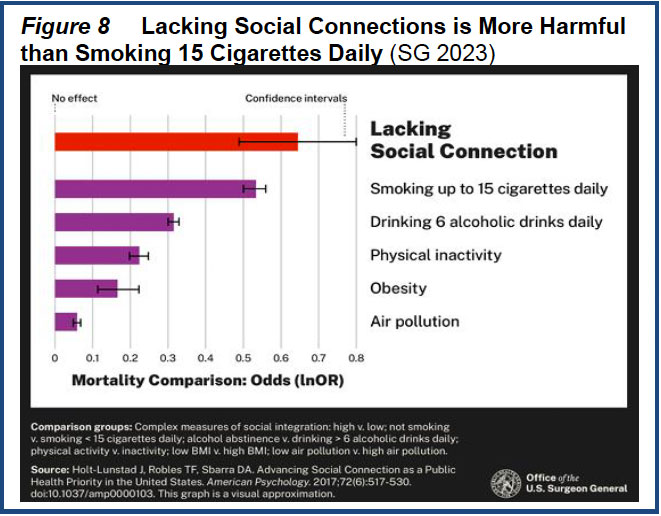

What is the greatest threat to your health? Smoking cigarettes? Becoming an alcoholic? Physical inactivity? Becoming overweight? According to the CDC, it’s lacking social connections (see graph below).

If you don’t have friends, family around you, or regular contact with other humans who can check on you or check in with you, that turns out to be very bad for your health. Many factors affect your social connections, and one of them is the built environment. As Granovetter reports in The Strength of Weak Ties (1973), casual social relationships, like the person behind the counter at a local coffee shop who says hello and asks how you are doing, are especially important for mental health.

I am in downtown Providence for a couple of days, and I witnessed that this morning when I was getting my coffee, and an elderly guy in a wheelchair came in, and they treated him as special. He comes in every morning. When you make a trip by active transportation—walking or biking—you are much likelier to have a friendly encounter than if you drive (Vancouver, 2016).

Now we find out, according to a study that came out this month, reported in Science Daily, that “Urban highways cut opportunities for social relationships.”

According to the summary, “Urban highways promise to get people to their destinations faster -- and bring them together. But at the same time, they reduce social connections between people within the city, especially at distances of less than 5 km, according to a new study.”

The findings should not be surprising to anyone who has walked around a downtown or urban neighborhood, who encounters a freeway. Even if there is some way across, the crossing is typically hostile to pedestrians—or at the least, not inviting. Freeways, particularly Interstates, create huge barriers in the urban fabric, and often disrupt the street grid. They cut off business connections to anybody who lives on the other side of the highway. And they also cut social ties.

"In this study, we use the spatial social connections of people within the 50 largest cities in the US to test whether the built environment—in this case, urban highways—is indeed a barrier to social ties, as has long been assumed in urban studies. For the first time, we are also finding quantitatively that this is the case," explains co-author Sándor Juhász. During his postdoctoral fellowship at the Complexity Science Hub (CSH), Juhász participated in the study.

When most of our urban highways were built, we didn’t think much about how car-oriented changes to the built environment might affect our social lives or health in general. But now we have learned a great deal about this topic, and it should influence highway construction policy. Traffic engineers and transportation planners need to think much more about health and not just the carrying capacity of travel lanes.