Study shows widespread new urbanist zoning reform

At the beginning of this century, just a handful of form-based codes (FBC) had been adopted nationwide. Conventional zoning, separating uses and housing types, was standard in US cities and towns.

A new analysis of more than 2,000 zoning codes across the US using artificial intelligence (AI) reveals “widespread adoption” of FBC principles and language—beyond what new urbanists may have suspected.

“An AI-based Analysis of Zoning Reforms in US Cities,” by Emily Talen of the University of Chicago and Arianna Salazar-Miranda of Yale University, shows that 89 percent of codes have any form-coding, 72 percent have a moderate FBC adoption, and 33 percent—about a third—have strong adoption.

The authors conducted a study by obtaining zoning codes from Municode, one the largest repositories of municipal zoning codes in the US. Municode is a codifier of legal documents for local governments. Talen says that the database is representative of US zoning codes, although the municipalities may skew larger, with more fiscal resources, than the average US town nationwide.

“Municode is a pay-to-use service and thus might exclude smaller and less affluent jurisdictions,” she says. Within the jurisdictions studied, form coding has been equally adopted regardless of wealth and demographics. “Our data shows that … places with high and low FBC similarity are comparable in terms of race, income, and other demographics.” The Municode database probably represents places where more development occurs, relative to all US jurisdictions.

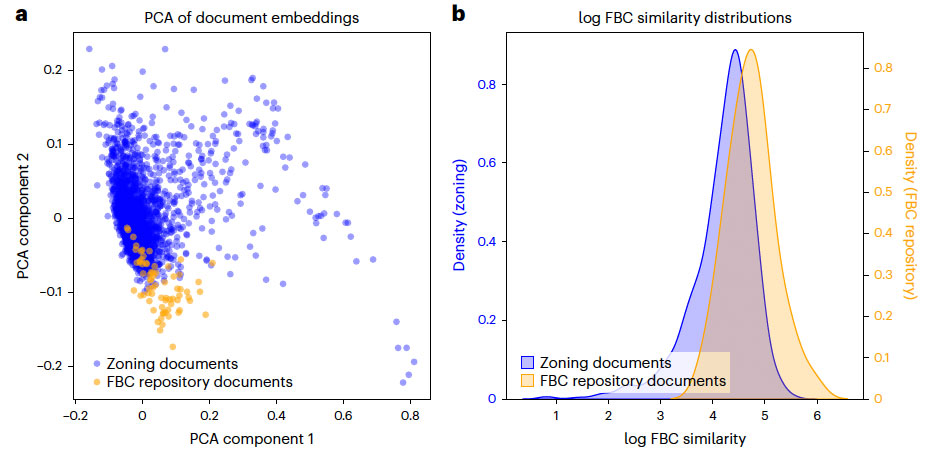

The authors compared the codes to the language in a repository of known form-based codes for similarities. A human expert also examined selected codes to ensure that the AI analysis jibed with the expert assessment—it did.

FBCs were created by new urbanists to address the difficulty in getting approvals for neighborhood development that follows principles of New Urbanism. “FBCs are associated with higher floor-to-area ratios, narrower and more consistent street setbacks, and smaller plots. We also find that places with FBCs have improved walkability, shorter commutes, and a higher share of multifamily housing,” the authors report. “These results show that planners have real opportunities to reshape urban environments toward more human-centered outcomes through thoughtful zoning reforms,” says Salazar-Miranda.

Many municipalities are adopting the concepts of FBCs without using the term, and FBC ideas are often being adopted incrementally.

Talen has been studying the extent of new urbanist zoning code adoption for 25 years—she coauthored a study of Illinois municipalities in 2000 that showed almost no towns—1 in 204—had regulations allowing for compact, mixed-use development. Asked what the two studies, taken together, revealed, she responded: “My thought is that progress on FBCs is really significant—what an achievement! One of the main points of our study is that FBC-like elements are filtering in (reduced setbacks, mixed use, etc.) without adopting the name ‘form-based.’ ” The use of AI “natural language processing” allowed the researchers to track these incremental growth of this land-use regulation concept.

“Using natural language processing techniques, we analyzed zoning documents from over 2,000 United States census-designated places to identify linguistic patterns indicative of FBC principles. Our findings reveal widespread adoption of FBCs across the country, with notable variations within regions.” While these zoning changes show up in many municipalities nationwide, they are slightly more prevalent in the South—which is not surprising, because many of the oldest “traditional neighborhood developments” are located in that region.

One caveat is that many municipalities have adopted FBCs for only a portion of the jurisdiction—often areas designated for higher-density growth. The researchers could not distinguish between city-wide FBCs and those that apply to specific areas within a jurisdiction.

Talen and Salazar-Miranda did not determine precisely when these form-based coding elements were adopted, but the vast majority certainly came in the last 25 years. Based on other sources, such as the periodically updated Codes Study, a large number of FBCs were adopted in the last 10-15 years. A 2022 study showed that new urbanist-type codes (codes supporting physical activity in the form of active transportation like walking and cycling) have been adopted by 26 percent of jurisdictions in 2020, up from 17 percent in 2010.

The researchers found no correlation between the level of regulatory restrictiveness and the degree of form-coding. “In other words, zoning codes can be highly restrictive and form based, or they can be highly restrictive and not form based,” the authors explain. This is not surprising, since some aspects of form-based codes loosen regulations, while others increase them. It depends on how they are applied.

Talen and Salazar-Miranda focus a lot on how coding impacts how buildings shape streetscapes, such as how setbacks impact street to height proportions and retail frontage. “These dimensions are crucial because they can enhance walkability, decrease car dependency and support local businesses by creating a more engaging and pedestrian-oriented public realm,” the authors note. However, aspects of streets like lane width, connectivity (gridded or dendritic network), curb return radii, and design speed are primarily determined by traffic engineers and transportation planners, not zoning codes. The extent to which walkable neighborhoods are created due to these zoning changes may depend on how well they are aligned with walkable street design.

Be that as it may, Talen and Salazar-Miranda show that new urbanist coding ideas are incrementally filtering into zoning codes—72 percent “moderate adoption” is particularly noteworthy. That’s good news for advocates of walkable communities. “Traditional zoning codes, which often segregate land uses, have been linked to increased vehicular dependence, urban sprawl and social disconnection, undermining broader social and environmental sustainability objectives,” the authors note. “Because these ideas are filtering in gradually, often without explicit labels, it's especially important to track zoning language changes over time. Natural language processing tools provide a powerful means to do just that,” says Salazar-Miranda.