Can American suburbanism be reversed in a generation?

The current conventional wisdom is that the market for housing in urban locations is so robust that demand far outstrips supply. Housing located within a healthy walkable neighborhood, whether new or existing, is expected to carry a significant premium. Walkscore has become seen as a meaningful predictor of value.

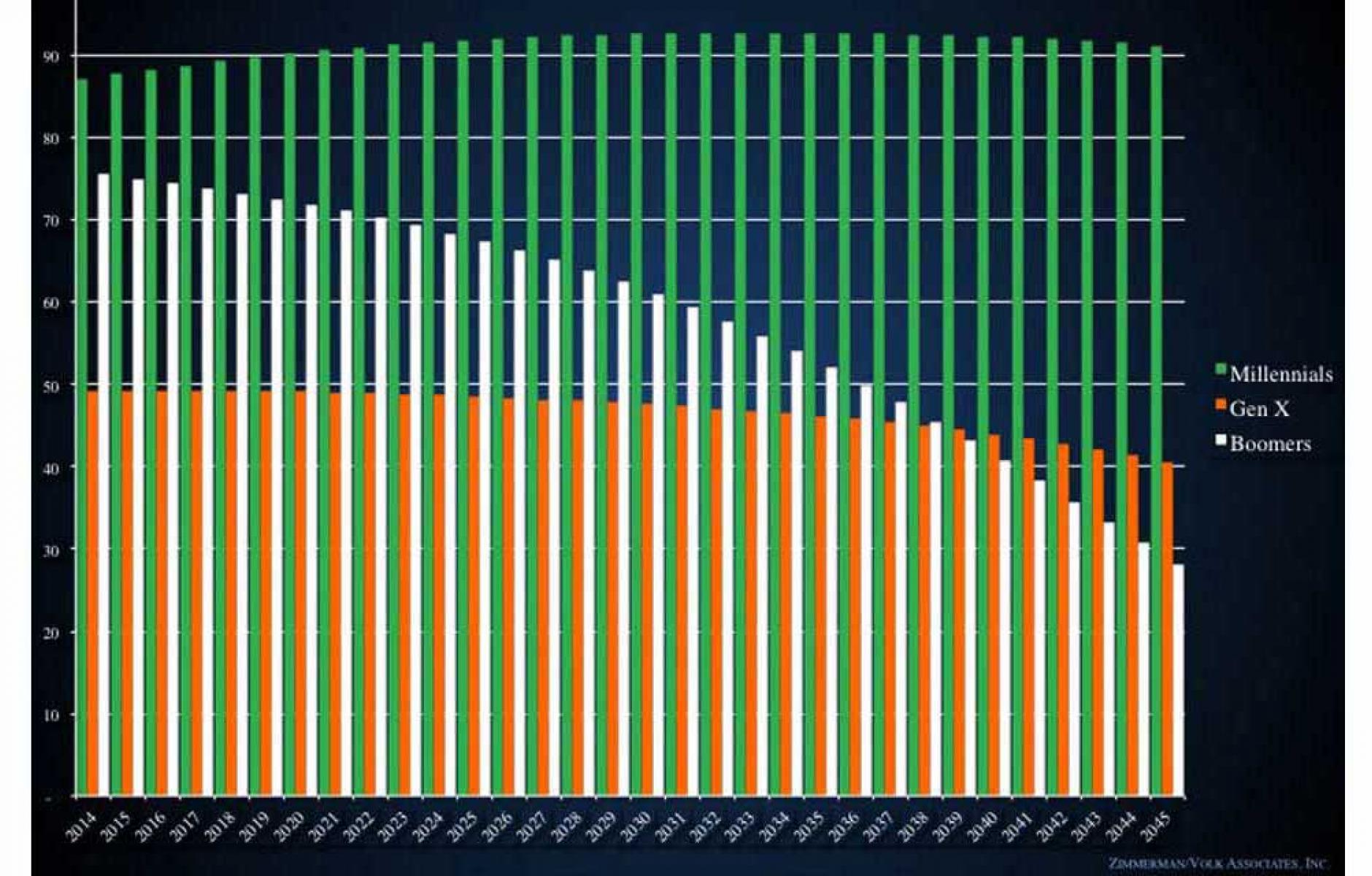

Since the turn of century, the demographic convergence of the two largest generations in the nation’s history, Baby Boomers and Millennials, both at life stages favoring community-oriented neighborhoods has formed the foundation for a nationwide urban resurgence. Only since the housing crash and the Great Recession, however, has it become commonly understood that the re-urbanization of America is now fully underway.

The impact has been felt in neighborhoods at every scale, from the nation’s greatest cities to small, walkable 19th century downtowns that have become the de facto urban centers for surrounding auto-oriented subdivisions.

Housing market dynamics, of course, vary widely from place to place, from day to day, and from household to household. Relevant dynamics include not only location, but also specific household demographics, economics and personal preferences. While broad implications can be derived from the lifestages of generations, there are other distinctions among households that can be more meaningful than age cohort. They are less often discussed because they are so challenging to define, much less quantify. Chief among these is preference for urban scale; there are those who would be very uncomfortable living in the density and diversity of a great urban center, and conversely others who would settle for nothing less. Then there are issues of taste—for example, contrasting those who prefer the gloss of the new versus those who prefer the patina of age—that can have a significant influence on housing preferences at the level of the individual building and unit.

Examined broadly, it is clear that a transformation of the nation’s settlement patterns is well underway. Both the near-term and long-term prospects for housing and neighborhoods are being influenced by the huge Millennial generation, born between 1977 and 1996, who in 2010 eclipsed the Baby Boomers to become the largest generation in American history. The Boomers and Generation X also contribute, but it is the Millennials who will be driving housing markets for decades to come.

When compared to earlier generations, Millennials are greener, more diverse in race, ethnicity, culture, sexual orientation, more gender fluid and, of course, since the oldest of them are still under 40, they are more unsettled. Millennials are much less likely to own a car, or even have a driver’s license. They are much more likely to be renters, not only because of age and life stage, but also psychologically and economically. Their skepticism about ownership is due to their coming of age at a time when $7 trillion of housing equity evaporated. The chief financial constraints are a combination of slow job growth and massive student debt, making amassing a mortgage down payment challenging. Concern about debt among Millennials is so great that in a recent survey 30 percent said they would sell an organ if it would erase their student debt.

Millennials’ life stage, financial circumstances and attitude toward ownership housing threatens to clog the whole system of ownership housing. For several years, first-time buyers have been well below the historical average of 40 percent share of housing sales. This year first-timers are just 32 percent of buyers. The low percentage of first-time buyers slows the ability of growing Gen X families and other potential move-up buyers to sell their houses, ultimately hampering empty-nest Boomers’ efforts to sell their houses to move to more appropriately-sized and located dwellings.

Millennials are still mainly singles and couples, part of the great demographic convergence with the Boomers who are also now mainly one- and two-person households. The 61.6 percent of American households composed of singles (28 percent in 2015) and couples (33.6 percent) stand in stark contrast to the 62 percent of the nation’s housing stock that is composed of single-family detached houses, many of which were designed to accommodate the traditional American family.

Once Millennials begin to start families in significant numbers, their preferences in aggregate may shift toward houses, attached or detached, with a yard. But whether that shift will be as marked as it has been in predecessor generations, and whether they will choose houses in exurban auto-oriented locations, remains to be seen. It seems likely that many of those Millennials that do chose a house with a yard will seek one in a walkable urban neighborhood. Based on emerging trends in cities across the country, it also seems likely that a much larger percentage will choose to raise their families in higher-density urban neighborhoods.

Millennial families’ continued embrace of walkable urbanism will depend on the success and quality of re-urbanization, particularly in smaller-scale urban centers, and whether a range of housing types can be developed, redeveloped, restored or maintained within these walkable neighborhoods. And, perhaps more importantly, it will depend on whether these dwellings, whether for-rent or for-sale, will be affordable to a wide spectrum of households.

Despite the strides made in re-urbanization, much of the new housing in walkable neighborhoods is of low-quality, poorly designed, poorly detailed and poorly constructed. While this is disappointing to urban advocates, there is no reason to expect that urban housing would be exempt from Sturgeon’s Law that “90 percent of everything is crap” or any different in quality from new housing in exurban subdivisions. Just as the family households at the end of the last century accepted ersatz “colonials” sited among a tangle of culs-de-sac, today’s community-oriented household will forgive much in an individual dwelling when it is located in a walkable neighborhood with meaningful pedestrian destinations.

The importance of walkability may be challenged by the reality of the self-driving car. They could become ubiquitous low- or even no-cost personal transportation options subsidized by the value of the Big Data generated by their use.

The combination of Big Data and the autonomous vehicle will surely have a profound impact on settlement patterns. We just don’t know what it will be. The self-driving car could enhance urban neighborhoods by eliminating the need for parking, even in urban centers that lack meaningful transit; one would simply drive home to a dense walkable neighborhood and send one’s car off to recharge at a remote parking facility on the outskirts. Conversely, and ominously, the self-driving car could revive the appeal of the cheap house in the remote exurbs, resuming the great thinning out of America; that commute, however lengthy, could be a relaxed one spent reading, chatting, texting, snacking or snoozing while being chauffeured by one’s Big Data-sponsored free autonomous vehicle.

Thoughtful decision makers, in both the public and private sectors, are concerned that plans made today—particularly regarding transit and parking—without considering the impact of autonomous vehicles could be obsolete in a decade’s time.