A small Michigan city embraces walkable urbanism

When CNU meets at its annual Congress in Detroit this coming June, participants will also examine places like Birmingham, located four miles to the north of the primary city.

After three decades of 20th century population loss and commercial decline, Birmingham, Michigan, committed to building a new identity: “The Walkable Community.” Now, thanks to forward-thinking planning across multiple sectors, the city has grown steadily since the turn of the millennium—even in the midst of economic decline across its region.

Birmingham, a city of 20,000, had been the victim of decades of bad planning and economic decline. A 1960s "ring road" highway diverted traffic from downtown, while construction of high-rises led to a backlash against density that stopped new development in the core. By the 1990s, the city’s historic Old Woodward Avenue had become an over-wide highway.

After losing two department stores and two cinemas, and facing competition from a mall a few miles away, Birmingham citizens and leaders were ready for change. In 1996 the city resolved to pursue a new strategy of calming traffic, building parks, improving streetscapes, and reforming regulations.

To guide their efforts, Birmingham leaders adopted a new motto for the city: "The Walkable Community." Since the city's change of direction, more than 3 million square feet of commercial development has been built in 30 major mixed-use projects.

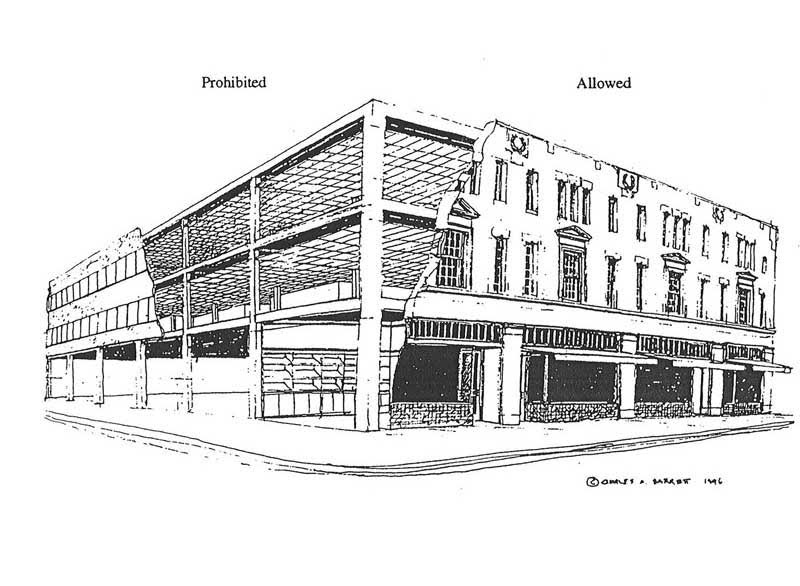

“In Birmingham, single-story zoning was changed to a multistory option contingent upon a higher-grade architectural façade,” says urban designer Michael Campbell. “The city benefited also from numerous existing parking garages that have enjoyed greater utilization at night since the plan went into effect.” A form-based code followed--one of the first adopted by any city--and Birmingham has become more urban in the last two decades.

The city’s main street, Old Woodward Avenue, was narrowed to two lanes with a center median and diagonal parking—one of many traffic-calming projects.

The plan resulted in the creation of a prototype Kroger supermarket that has been influential in other municipalities. The store features parking in the rear and liner stores on the street. A 12-screen downtown movie theater shows similar creativity. With no dedicated parking, the cinema is built to the sidewalk on all four sides and features liner buildings.

Duany Plater-Zyberk (DPZ), Gibbs Planning Group, and McKenna Associates created the mid-1990s plan that is still having an impact. City leaders applied similar techniques and principles to the Rail District (1999) and the Triangle District (2007).

Today, Birmingham's downtown now has a Walk Score of 92: “walker's paradise” The city’s downtown boom has continued even through the Great Recession, when the city continued to see mixed-use development. "Birmingham now has the highest commercial rents and land values in Michigan and is considered one of the most walkable downtowns in America," according to a report by the Michigan CNU chapter.

Today, Birmingham attracts shoppers from all over the Detroit region. “Birmingham's downtown district has many coffee houses, ice cream parlors, upscale apparel and home furnishing shops, restaurants and theatres,” notes Wikipedia. Even Google operates its Detroit-area offices there.

In many downtowns, the older buildings look better. In Birmingham, the reverse is often true, Campbell says. Many recent visitors are probably not aware of a large number of structures were built in the last 15 years—because they fit in so well with their surroundings as part of a carefully-planned, human-oriented strong Michigan community.