New eco-city combines ancient practice and modern technology

A new city rising on the edge of the Arabian desert may become one of the most sustainable cities in the world. Perhaps ironically, this attempt at creating a low-carbon city is occurring in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, which has grown wealthy exporting hydrocarbons to the world. Yet it’s not pouring money into the making of a sudden utopia. Planners are gradually assembling the elements of Masdar City, putting it together patiently and learning a lot along the way. Their “greenprint” for sustainable city making is becoming a model for the Middle East and possibly the world.

Masdar City is a project of the Masdar company, founded in 2006, a wholly owned company of Mubadala Development Company PJSC, an investment vehicle of the Government of Abu Dhabi. Masdar works on the development, commercialization and deployment of clean energy.

"The leadership of the UAE had the vision to harness the country’s oil wealth to diversify the economy based on knowledge and innovative technology," says Anthony Mallows, executive director of Masdar City. "That is why they established the Masdar Institute in partnership with MIT, with a new city to be built around it–to accelerate knowledge development."

Mallows speaks of the city’s three main purposes: to show bold leadership; to help diversify the UAE’s economy; and to demonstrate – to create a useful “greenprint” of sustainability.

“It’s about doing more with less,” he adds. “And it’s something being realized over time, not as a single project by a single entity. We’re creating joint ventures and welcoming other developers, raising local and global capital.”

It is a work in progress with ongoing adaptations and openness to opportunities as they arise. A large scale model, on the floor of the Cityscape exhibition in Abu Dhabi last month, shows powerful elements of the original design by Norman Foster. The city forms a great square on the flat desert floor. It is mostly low-rise, set out in four large residential quadrants that surround an institutional and office core.

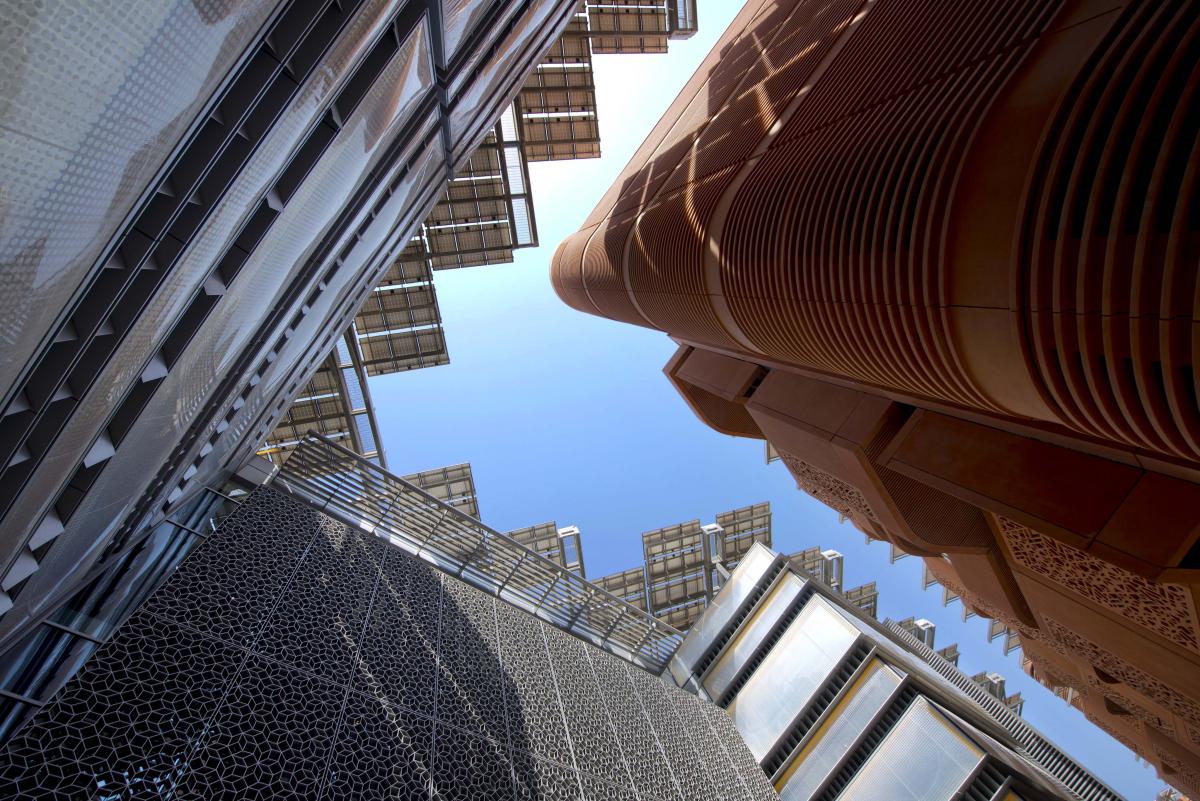

As laid out by Foster, the city is oriented to prevailing winds, with relatively narrow streets shaded by buildings closely set along them. This creates natural breeze and shade to cool the streets, in a region that reaches 50 degrees Celsius in summer. In this it follows the vernacular pattern of old cities of the region, of Cairo and Muscat. Indeed, it’s been demonstrated that in the small part of the city already built, the streets are comfortable for people longer into the warm season, compared to the wide sun-drenched streets of the rest of Abu Dhabi.

Looking at the model, senior design manager Chris Wan points out the hierarchy of space from very public to very private. Within the extensive grid of public streets are the sikkak, the narrow passages, as they’re called in Arabic. “These lead off from the public streets into quiet spaces amidst the building groups,” he explains. “It makes a rich grain.”

Overall it’s a fusion of traditional elements in a modular grid that will accommodate mass transit. And the streets will be given form by novel building forms and materials, as attempts to create net-zero energy structures proceed. Its central core is complete, anchored by the Masdar Institute that is dedicated to developing and commercializing clean energy technology from non-carbon sources. The Institute has approximately 500 students and 100 faculty members. There are also regional headquarters for Siemens and several other companies. Nearby is the new headquarters of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

The central core with the Institute and corporate buildings rests on a slightly raised square platform, a legacy of Foster’s initial design. The rest has yet to be built out. A soft S-curve flows through the middle of the model, showing the path of a planned light rail with four stops on its way to central Abu Dhabi. The heavier metro, an ambitious project of the Abu Dhabi municipality, will have one stop next to IRENA. And another system, a “group rapid transit,” will follow the boulevard that holds the central portion of the city in an enclosing square, serving as an internal circulator connecting communities in the four quadrants.

There’s even a PRT – a personal rapid transit – the first ever put into operation in 2010. The cute little pod-like cars run on one route from a parking garage to a station beneath the Institute at the center of the city. The system was intended to have a web of routes running below the city, which would be built upon raised platforms. This would eliminate all conventional cars, with internal transportation served by the battery-powered PRT cars recharged from solar sources. As planning went forward, this feature was considered to be of less importance for achieving overall sustainability goals, although one PRT route was retained as a functioning system and useful demonstration.

As a city built on a grid that gathers natural breeze, linked internally and externally by transit, and with an educational institute at its center, Masdar will strive to be what planners call a complete community. “It will be a place where lifelong learning is possible,” says Chris Wan, “and where ongoing innovation will occur.” Wan, a Hong Kong native who studied architecture in Britain, is contributing to that now, with his participation in the development of an “Eco-Villa”. The prototype house, requiring 42% less energy than a typical new house in Abu Dhabi, will be a model for residential builders in the city. When equipped with solar panels it can achieve “net zero” energy consumption.

Lifelong learning and ongoing innovation are the more subtle aspects of sustainability, what might be called the cultural aspects. The Masdar Institute, at the center of the community, should help to build this culture. It’s on the leading edge of thinking about an alternative clean energy future, which, necessarily, will be quite different from the UAE’s recent past.

In five years, Mr. Mallows affirms, the city will be 35% complete. The planners anticipate 40,000 residents and 50,000 workers at build-out. But it will not exist in a self-contained vacuum. Some residents will work elsewhere in Abu Dhabi, while some non-residents will come into Masdar City to work.

Indeed, the city’s development is closely related to the ongoing growth of the city of Abu Dhabi, capital of the Emirates. And its planning is closely linked to planning for the larger city and region. Masdar City is strategically located on Abu Dhabi’s southern edge, adjacent to the international airport and a 45-minute drive from Dubai. Its development guidelines, which apply to all developers’ proposals, are integrated with the development standards and sustainability requirements of Abu Dhabi’s Urban Planning Council (UPC).

Abu Dhabi has taken comprehensive planning quite seriously and made remarkable progress. The city lays over a group of low islands that extend into the Gulf. In 2005, the Emirate was in the midst of a building boom and faced with stark choices about its development. It was considering the placement of an expressway through the city to reach the growing downtown area and the Corniche Road along the sea. At that point, the government hired Canadian planner Larry Beasley, of Vancouver, who guided a strategic planning process that led to Plan Abu Dhabi 2030, which was adopted in 2007. The UPC was founded the same year to implement the plan.

Guiding a national capital of 1.2 million, and forecast to rise to 3 million in just fifteen years, the strategic plan for 2030 has tried to focus development and stitch the city together. The UPC has been able to guide the development of a more coherent city, and the fruits of master planning are now apparent, with much more controlled growth onto the mainland and adjacent islands. The expressway was channeled below ground to preserve the urban fabric, while isolated areas of development were largely avoided. The emphasis of the plan has been to connect and pull the city through to the undeveloped islands, with new bridges built as extensions of the city’s grid.

The UPC has been empowered to create master plans for all development areas. It has laid out beautiful urban expansions on Saadiyat and Al Reem Islands. New cultural and educational precincts are planned, with branches of New York University and the Louvre Museum already built. Its master plan for Zayed City, just about to start construction, is an outcome of the ’07 strategic plan, which foresaw a new seat of the national government in a concentric array where seven main boulevards converge. It has worked closely with the transportation authority on plans to connect the city’s far-flung parts together with a metro system.

The UPC is now working at all scales. Its successful proactive, strategic planning has been complemented with good reactive planning – regulation. A series of manuals authored by the planners provide specific development standards. There is a city design manual, a utility corridor design manual, a public realm design manual, and a well-regarded street design manual that follows a “complete streets” method and has won an award of the Institute of Transportation Engineers. The street design and utility standards are now integrated in a new on-line tool that allows road planners and utility engineers to work from the same file, virtually evaluating new development applications.

Masdar City’s development is moving forward under these standards. The UPC has created its mandatory Estidama standards, comparable to the LEED standards of the US Green Building Council (which are voluntary). It recently approved master plans for new phases of development, and Masdar planners have voiced their intention of being the first community to achieve a “4 Pearl” rating for community development in the UAE. This high rating would indicate that Masdar City has created a high quality of life for its residents while achieving key environmental standards, such as reducing energy and water demand, waste and carbon emissions. More than this, it would indicate the high level of interdisciplinary planning for the city, encompassing innovation and knowledge exchange.

Learning and innovation are at the heart of the idea for Masdar City. The Masdar Institute is pursuing numerous projects in green building and urban sustainability, seeking collaborative relationships with the companies located there and others worldwide. Numerous projects are underway in energy management and storage, geothermal energy, solar energy and photovoltaics. There are now 12 experimental projects in the works, including an algae-to-biogas project, and a large solar panel assembly in the desert.

Mallows sees Masdar City as a model for the way to build cities of the future, and he’s clear about its potential to realize the world’s most sustainable urban development. Still, he sees its development as an ongoing process, not something that can be achieved quickly. Even communicating what they’re trying to do can be difficult. “We’re looking for a good platform to explain what we’re trying to explain,” he says.

Looking at the great scale model of the future city, Chris Wan was considering the many questions of sustainability. He pointed to the small 10 MW solar panel array on the edge of the site, which lowers the city’s carbon emissions. “Someday that will be replaced with urban development,” he predicted, “because its closeness will compel development there.” Meanwhile, he thought, more energy would be gained from building solar plants further out in the desert. But he acknowledged it’s one of many questions about Masdar City, at this point.

“Sustainability is more about the questions we’re asking than about the answers,” he said.