How can we accelerate local code reform? Act more like the Tortoise, less like the Hare

Across the country, many small and mid-sized cities and towns are looking for ways to foster greater Main Street and downtown development, redevelopment, and revitalization. One barrier to these efforts is local codes and ordinances, which are the very DNA of what makes—or breaks—a place. Zoning, street standards, and other codes dictate where and how much parking is built, the width and location of sidewalks, where buildings are placed. They also shape other components of the built environment to create a thriving neighborhood or fragment a community.

Most of today’s codes were written to accommodate and guide the post-war housing boom many American cities and towns experienced. Now, nearly 70 years later, many of these codes no longer serve the community’s vision and goals. Yet many jurisdictions have not updated their codes because the process is time consuming and requires considerable political will and resources. Cities short on funds and staff may not be able to effectively overhaul their codes or fully engage with stakeholders, and as a result they could fall further behind wealthier jurisdictions.

In 2016, CNU formally launched the Project for Code Reform to streamline the code reform process by providing local governments greater access to coding tools, and to do it in a way that meets planners, mayors, and planning commissioners where they are: politically, financially, and administratively. Instead of guaranteeing a great place, the Project for Code Reform provides approaches that enable a great place. This is a significant difference: guaranteeing a great place requires a complex code that takes into account a range of issues, while enabling a great place focuses on the critical land use elements required for vibrant, walkable places. Putting these elements in place can involve small but critical changes to codes—often simplifying or removing requirements.

We want to help local leaders who are trying to create vibrant Main Streets, walkable neighborhoods, and an active public realm but have limited planning staff and resources. By mitigating the broader complexities that constrain resource-strapped cities in their efforts to foster equitable development, we seek to advance an incremental coding reform that addresses critical coding barriers to creating great places. In this way, the Project for Code Reform can be used to support decreased regulations (by simplifying the existing code) and reduce the barriers to entry for developers and support small-scale developers (by reducing regulations). It also better responds to local business needs and conditions (by incrementally changing the most problematic provisions). These outcomes can increase equitable development because of how the codes respond to local needs and conditions.

Elements of a code: Incremental change

Our team of code reformers—Susan Henderson, Matt Lambert, Mary Madden, Marcy McInelly, Karen Parolek, Dan Slone, and me—worked with the Michigan Municipal League and Michigan’s Redevelopment Readiness Program to develop a streamlined coding process for the 500+ cities and towns in Michigan.

Channeling Rick Bernhardt, the innovative and persuasive former planning director of Nashville, we kept pivoting our conversations back to the basics: “If you do nothing else, do this.” But what was the “this?” We quickly identified the five most problematic areas to placemaking: parking, form, use, frontages, and public realm.

Understanding where these changes might be applied within the city or town is equally important. Code requirements differ with each context; the requirements needed for a Main Street are different than those needed for a residential neighborhood. Coding is not a “one-size- fits-all” process: understanding the intention of the place is crucial to designing a coding framework that enables good urbanism.

The Michigan Municipal League gave us a virtual tour of hundreds of Michigan places, and four “urban” place types emerged: Downtown District, Main Street Corridor, Downtown Adjacent, and Main Street Adjacent. Specific code changes were identified for each coding element in each place type. The resulting strategies are currently in the form of a Draft Coding Matrix, which identifies incremental steps a city or town could implement in each of the critical coding areas.

The Project for Code Reform is centered on incremental change. Many code reform processes seek to overhaul the entire code. The all-or-nothing approach has significant potential to morph into a contentious and arduous process for all involved, It can daylight simmering community tensions, create strong NIMBY reactions, and can lead to other, unresolved, community issues.

Our approach focuses instead on smaller, achievable changes. This incremental approach lays the foundation for creating great places by addressing the most problematic coding issues. And by allowing local governments to set their pace for code changes, it enables them to prioritize their coding efforts, respond to the community’s vision, needs, and fosters greater community learning and understanding.

Essential to this approach is progress toward an ultimate vision or aspirational goal of a code reform effort. The Coding Matrix provides coding language in critical areas to address what most cities have found to be the most pressing coding problems. But fixing these issues will not guarantee vibrant, diverse places. For many cities and towns, a comprehensive coding reform will be beneficial. We contend that engaging in such a process will be easier and more equitable because of the progress (and engagement) of the incremental code changes that have occurred in the year(s) prior, building political will.

Fear of change often makes complete overhauls difficult. Most folks like their community, and few are ready for a wholesale facelift. This is why Tactical Urbanism can be so powerful: it enables a community to see firsthand and experience specific land use or street design changes before committing to the change, e.g., how a bike lane might work, what the street would be like with buildings built up to the sidewalk. In a similar way, the Coding Matrix allows a community to test smaller code changes, prove the coding changes work, and build political will.

Fostering equitable development

The Project for Code Reform can also be used to create more equitable and accessible places. The incremental approach levels the playing field between those cities and towns with limited staff capacity and resources and those with robust planning departments because it empowers municipalities of any size to easily modify some of the most problematic portions of their codes.

These coding changes seek an active public realm, which includes a commitment to a diverse community. As Jane Jacobs said, “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” Because the incremental approach is responsive to local conditions, a place is more likely to embrace the existing and changing culture. When places are designed for all people, the same opportunity to experience quality spaces, dignified settings, and accompanying human enjoyment is provided. Equity of experience can be in the public realm or in the ability to engage in public discourse about the future of your community. And that’s what this coding reform seeks to achieve: equity in process, equity in place, equity in experience, and equity in beauty.

All places deserve to be great places. By developing a Coding Matrix with language designed to be dropped into existing documents, the Project for Code Reform reduces the effort, expense, and complication of code reform. We heard directly from a number of small, resource-constrained Michigan cities and towns that they would be able to implement some aspect of the matrix the very next week.

Simultaneously, the incremental approach enables a community to adapt and digest change in a singular neighborhood or district before moving to the next update, building political will and community support throughout the process. Additionally, incremental changes could reduce costs for development and local government. For example, reduced parking requirements lower the market barriers to entry and support small-scale developers, which can enable a small-scale, more responsive approach to revitalization.

Tukwilla, Washington

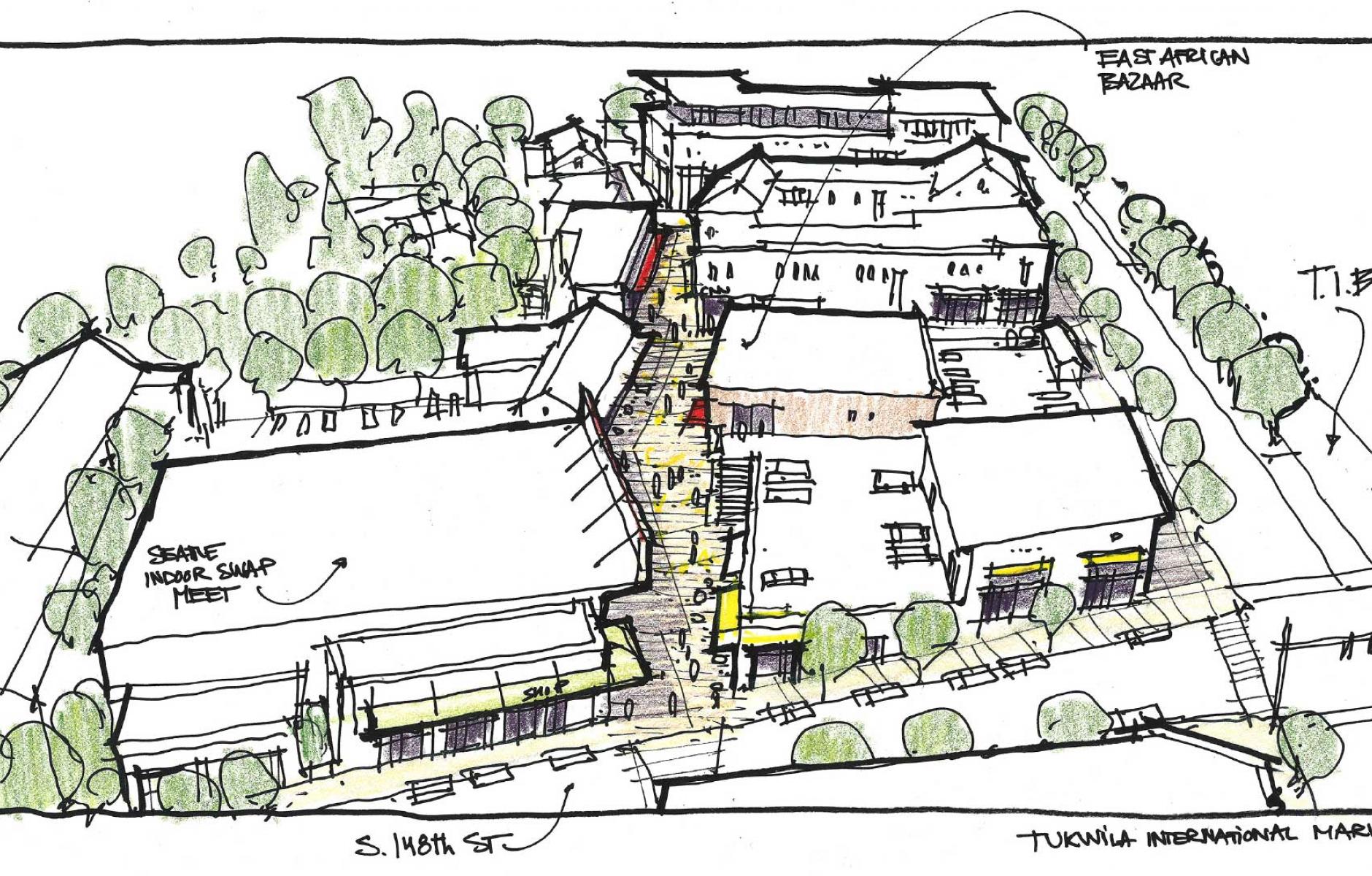

This incremental coding approach was recently applied in Tukwilla, Washington, a low-income community with a 38 percent refugee and immigrant population. The community wants to transform their arterial into a walkable Main Street to leverage a new light rail stop. Given the demographics of the community, cultural sensitivities and inexpensive development approaches are required.

To respect these conditions, the city is not primarily seeking a large-scale developer to propose a new mixed-use town center. Instead, the proposed incremental changes enable the local government to slowly and incrementally modify the existing arterial in a way that keeps local business, respects the mixing bowl of cultures, and provides very small-scale retail spaces that act like incubators for immigrant businesses. By focusing on small coding changes rather than a complete overhaul, the arterial becomes more attractive to developers, particularly those focusing on affordable housing options in combination with commercial, thereby responding to local business needs and conditions.

This is not to say, of course, that larger-scale developers would not be invited or sought. Indeed, one idea is to design and build a mixed-use multi-modal transit hub immediately adjacent to the light rail station, which is a project best completed by a more experienced and larger developer. Implementing scalable modifications to the city’s coding framework creates space for both small-scale and large developers.

The Project for Code Reform is an effort to provide solutions to cities' most pressing coding issues. Returning continuously to the idea of “if you do nothing else, do this,” limited coding changes were developed in parking, use, form, public realm, and frontages areas. These changes must be applied within the context and scale of specific districts, corridors, or neighborhoods. Finally, these incremental changes are designed to build the political will and community experience toward more comprehensive reform. Vital to this effort is keeping the very real struggles of the local government front and center: they want to do more, yet they have less, so let's give them the tools they need.