Plan to retrofit suburban to mixed-use urban

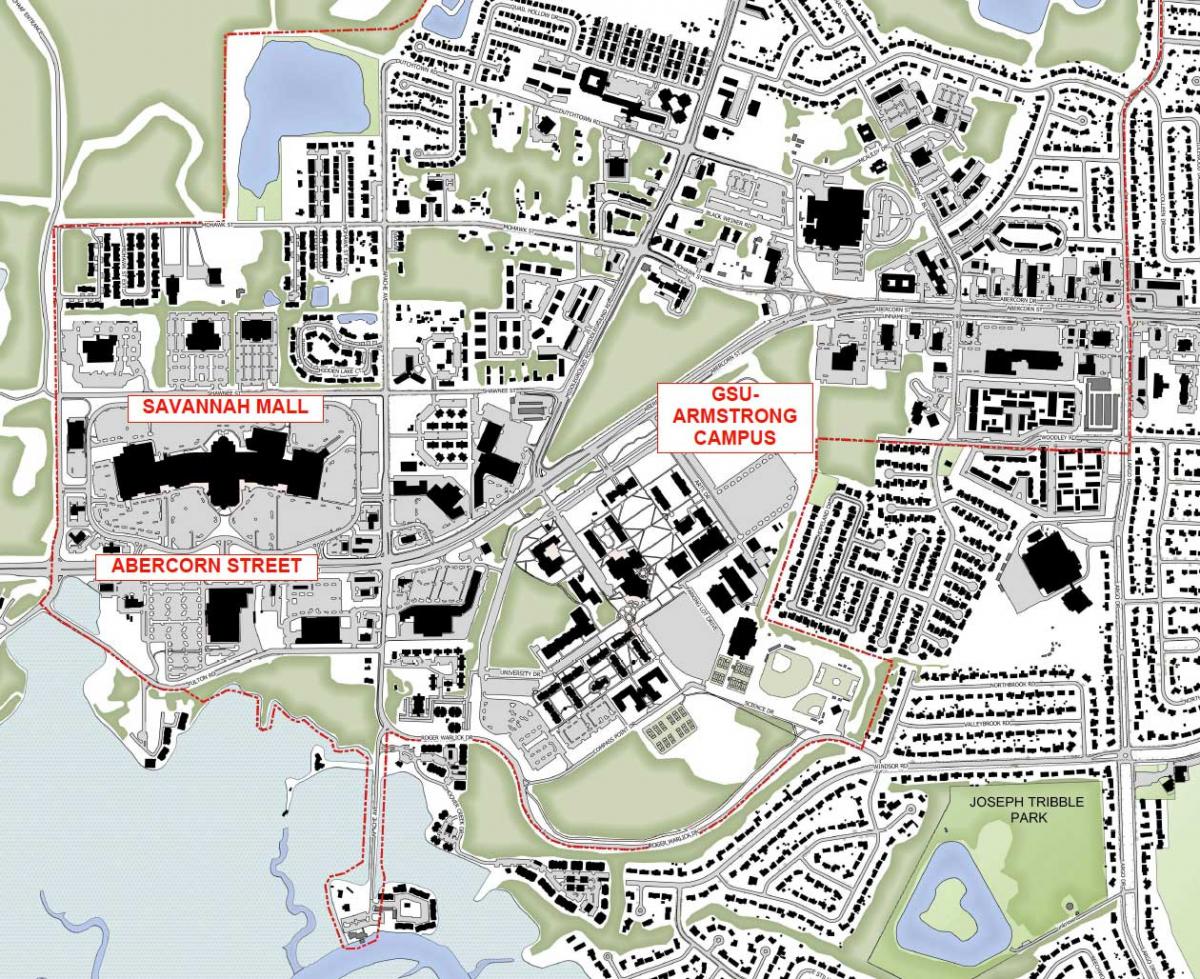

Consultants proposed a new town center for Southside Savannah that connects to the Georgia Southern University Armstrong (GSU-Armstrong) campus and transforms a busy, automobile-oriented thoroughfare into a boulevard. A failing mall could also be redeveloped into mixed-use urban blocks on the scale of Savannah’s historic district.

Over time, the plan would add a layer to Southside that doesn’t currently exist—walkable, bikable urbanism with useful green space, made possible by a growing academic institution.

The suburban retrofit vision was presented at the end of a four-day "Legacy Project" of the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) in advance of its annual Congress, to be held in Savannah May 15-19. Legacy Projects are launched so that the Congress will leave an enduring mark on the host city and region.

A large-scale suburban retrofit requires many moving parts—transformation of thoroughfares, new blocks and streets, mixed-use development, re-imagined green spaces, and revised development regulations. The plan covers all those elements, and city officials reacted positively.

“My colleagues and I from City Council were thoroughly impressed with the Southside Suburban Retrofit presentation by the team from David M. Schwarz Architects from CNU,” noted Mayor Eddie DeLoach. “Their approach to the area was dynamic and provides the City new ideas to spur redevelopment opportunities in a traditional suburban setting which would complement our National Landmark Historic District and pristine waterways. This could not have been possible without CNU’s Legacy Project Program.”

Developed in late 20th Century, Southside is located about 10 miles from the city’s famous historic core planned by James Oglethorpe in the 1700s. The GSU-Armstrong campus was established in 1965 in what was then an undeveloped area outside of the city.

“The plan grew out of what we heard from residents, who said in various ways that ‘we want our own downtown,’ ” says Michael Swartz, who led the design session. “Southside residents are proud of the historic core, but it’s not a place where they go to meet daily needs. It’s not center of their community.” A new town center could be shared between residents, faculty and students of GSU-Armstrong, and military personnel from nearby Hunter Army Airfield.

The CNU plan was based on the following principles:

• Encourage new development stemming from the anticipated growth of Georgia Southern’ s Armstrong Campus to have a mix of uses that form complete neighborhoods

• Focus population growth within major activity centers

• Promote safe walking and biking as primary means of transportation

• Increase opportunities for public transit in Savannah’s Southside

• Write or revise development rules to achieve the desired outcomes

• Apply lessons learned from the Southside study throughout the City of Savannah

The 268-acre Armstrong State University campus recently merged with GSU, which creates substantial opportunities for GSU-Armstrong growth. GSU, which has a main campus at Statesboro, Georgia, plans to expand its public health, nursing, education, and engineering programs in Savannah. This expansion could be the linchpin of a new town center for Southside located across Abercorn Street, a busy, car-oriented, six-lane state thoroughfare, the planning team said.

A good way to create that town center would be to realign Middleground Road, a city-owned thoroughfare, to create a civic green across the university (see rendering at the top). The town center could grow incrementally from that green—to the west, the site of a failing mall, and to the east, in land owned by the university.

The university has never used that land because Abercorn is so difficult for students and faculty to cross. Swartz and his team, which included smart growth transportation engineer Rick Hall, re-imagined Abercorn as a multiway boulevard to solve the problem. Without reducing capacity, the proposed design allows pedestrians to cross two lanes at a time compared to the current six or more (there are turn lanes at intersections). The proposal would calm traffic for about a mile, making the area safer for pedestrians and allowing the university to expand across the road. Although the through lanes would be reduced, the boulevard includes lanes on both sides to carry local traffic. To the east, Abercorn (Route 204) becomes Truman Parkway, which has two lanes in each direction in places. “We are just continuing the same number of lanes that already exist to the east and the north, plus adding lanes for local traffic,” Swartz says.

The Savannah Mall, located about a quarter mile from the GSU-Armstrong campus, is another driver of the plan. Many tenants have left the mall, and broken escalators are signs of poor maintenance, Swartz says. “There’s a reason why the mall is failing,” Swartz says. “This part of Savannah is over-retailed.” A more recent Outlet Mall in the same market area is drawing customers from the Savannah Mall, and an older mall a few miles away on Abercorn is also doing better—not to mention nearby Walmart and other big box stores.

If the mall fails, the site could begin to redevelop incrementally. The mall site is rectangular, and so the design team applied the scale of blocks and a square that are similar to Savannah’s Oglethorpe grid plan. The redeveloped mall site would connect to the new town center and allow more urban residential development of townhouses and other “missing middle” housing types. If mixed-use development is to take place here, residential and university-related uses will likely prevail, with civic uses and limited retail and restaurants, Swartz says. The university expansion makes that vision feasible.

“Local residents feel a lack of a third place,” he says. There’s no place for students to go either. They have to drive 10 miles to downtown for entertainment. It would be nice to have a place of their own and could be a shared place with community.”

The design team also examined the underutilized natural assets of Southside, which borders on a marsh. New public spaces could provide sites for fishing, water access, and passive recreation—all connected to residents by bicycle and multiuse paths.

Much of the plan hinges on whether Abercorn can be transformed into something that is designed for more than automobiles. Technically, this can be done—but the change would need the support of the Georgia Department of Transportation. To get the DOT on board would probably require backing from the city, public sector, and university. The latter, a state institution, may have some leverage with the state DOT.

In the meantime, Southside has a plan, and that’s a start. As the city entertains redevelopment proposals for the area—whether from institutions, the mall owners, or others, the Southside plan provides a point of comparison.