Why new urbanists generated great ideas

The late urban planner Hank Dittmar writes that he “perceived a dissonance between what [he] saw and liked in cities and landscape and what was being taught in school.” Everything that Dittmar loved about cities—mixed-use, walkability, fine-grain diversity of buildings, the network of small blocks and streets, the close relationship of building to the public realm—was denied by prevailing theories, practices, and policies. That dissonance led him into a long career contributing theoretically and practically to Great Ideas of the New Urbanism such as Transit-Oriented Development and Lean Urbanism.

The New Urbanism and its ideas respond to that dissonance that many planners, architects, and developers perceived. I authored a book this year, published by CNU, on 25 Great Ideas of the New Urbanism, available for free download. There are more than 25 Great Ideas, but this book covered the most significant ones. And it marks an anniversary—it has been a quarter century since 1993, when the first Congress for the New Urbanism was convened in Alexandria, Virginia.

Why did new urbanists, and no other group, generate and implement these ideas? New urbanists weren’t the only ones to sense that dissonance. Jane Jacobs and Christopher Alexander were the most important theorists to brilliantly analyze and articulate the flaws of modernist planning in the 1960s. More than anyone else, Jacobs put the brakes on urban renewal and in-city highways, two policies that decimated traditional cities. Alexander began to point the way to more human-scale design and architecture.

Despite Jacobs and Alexander, conventional suburban design—also known as sprawl—was just getting started and was instrumental in the decanting of cities in the 1970s and 1980s. The new urbanists learned from theorists like Jacobs and Alexander, but noticed that nobody was offering an alternative to sprawl. Three factors allowed new urbanists to tackle the issue, according to Nathan Norris of the CityBuilding Exchange:

- Existing institutions failed to address the negative impacts of suburban sprawl. The professions most responsible for the built environment (architects, planners and engineers) largely ignored the negative impacts of suburban sprawl in the 1970s through 2000. Most academics also failed to address this issue. In the absence of others addressing this issue, the new urbanist practitioners have been ahead of others for decades.

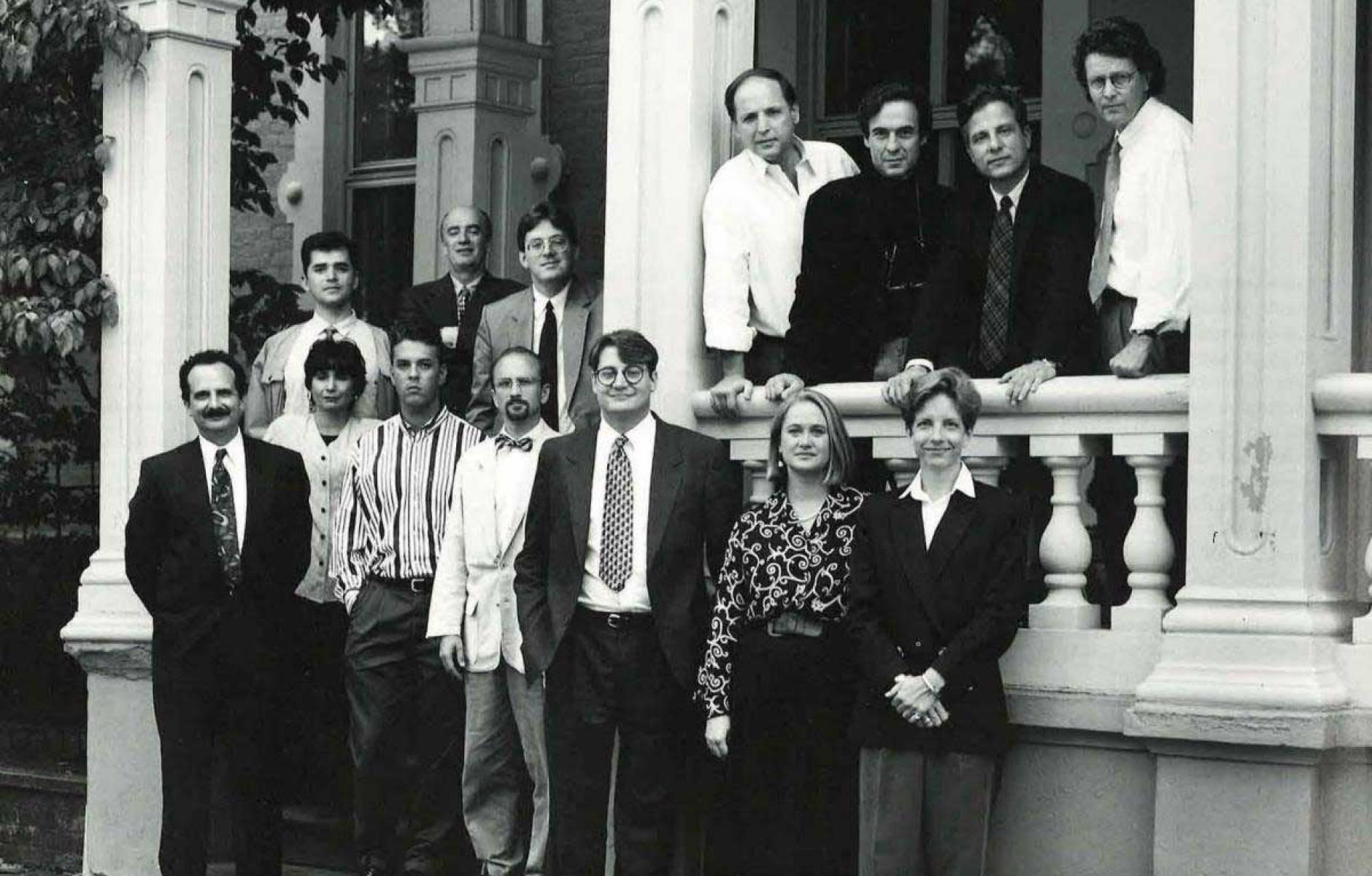

- Good leadership. It was especially hard to combat the entrenched status quo in the 1980s, and that fight brought together a few folks who helped each other through collaboration. We now call those people the Founders of the CNU. They were not only smart, but also tenacious, persistent, and willing to share ideas. Without those people, the 25 ideas would have developed much more slowly by others.

- A shared ethos. The most important reason for the generation of the 25 ideas has been an ethos that searches for solutions to problems while celebrating:

A. A holistic approach;

B. Pragmatism (e.g., precedent is highly valued);

C. The power of great design;

D. Constant improvement through incremental experimentation/innovation; and

E. Collaborative sharing (e-mail listservs, conferences, books, workshops, councils, etc.).

Nathan is right, but why did the institutions fail to address sprawl? I think the answer lies in complex changes to the operating systems of land use planning and development, each of which required multiple responses. The problem had to be addressed from many angles, hence the need for a multitude of ideas. The complex changes that led to sprawl included:

- Zoning. This became universally adopted all across the US and in many parts of the world. It made the way we had built for thousands of years illegal.

- ‘Dentritic’ street organization. We stopped building connected street networks in the late 1940s. Transportation engineers and planners were trained to design streets in a new way, and these professions were backed by the full power and resources of government at the federal, state, and local levels.

- Real estate finance. A new system was put in place to support mass production of single family housing and single-use building types. Mixed-use and middle density housing fit like a square peg in a round hole. You couldn’t get these financed, and form follows finance.

- Retail types. The new thoroughfare systems concentrated rather than dispersed traffic. This opened up business opportunities for malls and big box stores.

- Building design. Architecture changed—favoring context-free sculptural forms suited for the isolated sites of suburbia.

- Development. The building industry changed radically, jettisoning and forgetting the forms and building types that were essential for walkable neighborhoods.

- Lifestyles. Americans began driving more and more in response to changes in the built environment.

- Hidden systems. Many of the changes were hidden in policies and codes that ordinary people could not see. Even the administrators of the policies and codes were only expert in particular areas, and they could not see the entire picture.

These multiple, hidden systems created cognitive walls that most people could not get their minds around. New urbanists not only had to address each of these problems, but also had to get people to see that other ways to build communities were possible and to act on that understanding.

In response, the 25 Great Ideas of the New Urbanism are both ambitious and practical, as the last quarter century has proven. Somebody had to take on sprawl. A multidisciplinary group with potential influence and understanding of the built environment, new urbanists were uniquely positioned to push back effectively against the status quo.