Failing golf communities not on par with neighborhoods

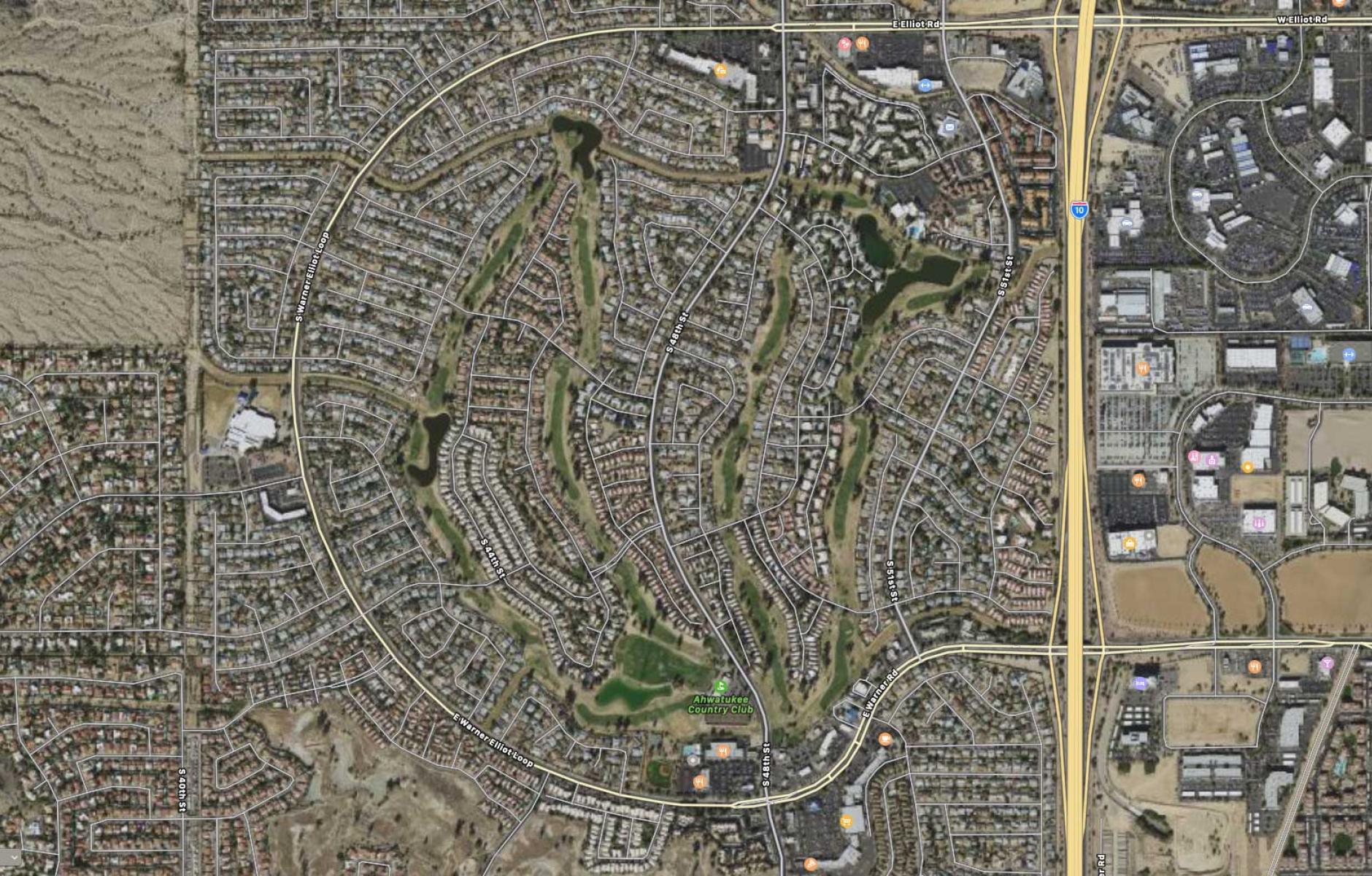

The failure of golf course communities continues to be a massive problem nationwide, according to an article in The Wall Street Journal. With 1,200 golf communities nationwide, and golf declining as a past-time, many homeowners face declining property values and are saddled with heavy membership dues that they no longer can afford.

When a golf course closes, the value of homes in an associated subdivision typically drop 25 percent—but may decline 40-50 percent if a legal battle ensues, the Journal reports. Developments are selling lots, once valued at a quarter million, for a dollar. Often, they can’t sell even at that price, because buyers must pay the course dues. The economic losses are likely in the tens of billions of dollars nationwide.

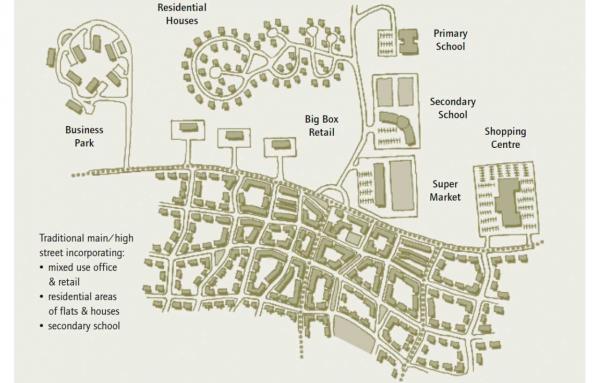

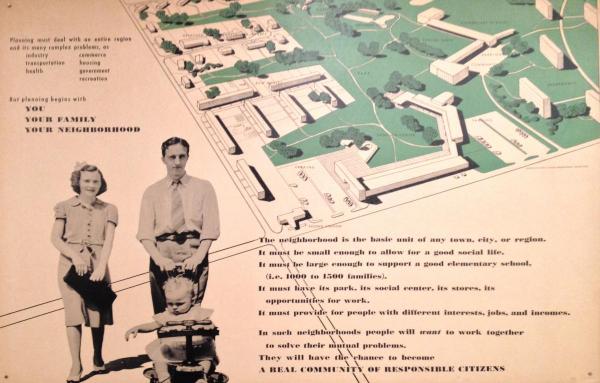

The problem is not just golf, but selling “amenities” without the density to support them. The new urbanist way is to build a mixed-use neighborhood—and that is the amenity. The neighborhood model has two advantages. First, a walkable neighborhood is probably about triple the density—which means that more homeowners can support common amenities like a park or a pool. Second, many of the amenities are self-supporting, such as main street businesses or a school.

This problem reported by the Journal was predicted two decades ago by new urban developer Bob Turner of Beaufort, South Carolina. In a paper, Sustainability Through Design, Turner pointed out that low-density developments spread too many amenities over too few homeowners, creating an unsustainable burden. New Urbanism’s higher density and more efficient infrastructure makes it more financially sustainable in the long run, Turner said. Instead of a clubhouse with restaurants, New Urbanism offers a main street with private businesses. Instead of an expensive golf course, New Urbanism provides parks, playgrounds, and schools that serve people of all ages.

The problems of golf course communities will be even more pronounced in age-restricted developments, predicts Turner, the developer of several traditional neighborhood developments, including Habersham in Beaufort County. “History has proven that for a society to be sustainable there must be a diverse population within that society,” he wrote in 1998, and that rings true today.

For “golf course communities,” the problem is likely to get worse before it gets better. The Journal writes:

Forty years after developers started blanketing the Sunbelt with housing developments built around golf, many courses are closing amid a decline in golf participation, leaving homeowners to grapple with the consequences. People often believe a course will bolster their property values. But many are discovering the opposite can now be true—and legal disputes are erupting as communities fight over how to handle the struggling courses.

“There are hundreds of other communities in this situation, and they’re trapped and they don’t know what to do,” says Peter Nanula, chief executive of Concert Golf Partners, a golf club owner-operator that owns about 20 private clubs across the U.S. One of his current projects is the rehabilitation of a recently acquired club in Florida that had shut one of its three golf courses and sued residents who had stopped paying membership fees.

More than 200 golf courses closed in 2017 across the country, while only about 15 new ones opened, according to the National Golf Foundation, a golf market-research provider.

Many golf course closures present opportunities for retrofit. Georgia Tech professor Ellen Dunham-Jones—co-author of Retrofitting Suburbia—maintains a nationwide suburban retrofit database, which includes 130 golf course retrofits. “A few have gone from 18 holes to 9 to build senior housing for the folks who want to ‘age in place,’ she said in an email. “Quite a lot have simply been filled in with more single-family homes. Some have been redeveloped with mixed-use—but more often due to deed restrictions as open space, they’ve been turned into parks, preserves, farms, even a cemetery. Even then, remediating the pesticide-ridden soils is quite a job. Houston and Louisville have incorporated them into regional park systems, in Houston’s case as flood control.”