Savannah adopts two CNU Legacy projects and a downtown plan

A little over a year after CNU 26 in Savannah, Georgia, that city’s council formally supported two CNU “legacy projects” and adopted a new downtown plan. Legacy Projects are launched each year to leave an enduring mark on the host city and region of the annual CNU Congress—and the Savannah projects appear to be on their way to achieving that goal.

One legacy project, in suburban Southside Savannah, envisioned the retrofit of the dead Savannah Mall and surrounding areas to create a new town center and neighborhood to leverage the economic power of a growing campus of the Georgia Southern University Armstrong (GSU-Armstrong). The plan, by David M. Schwarz Architects, has substantial support in the city.

The dead mall is located in a federal Opportunity Zone, which may facilitate financing for redevelopment. The plan calls for mixed-use urban blocks on the scale of Savannah’s historic district, including creating two squares. The big hurdle is the need to transform a large thoroughfare with fast-moving traffic into an urban boulevard. The vote is a first step to take the steps necessary to implement the plan.

The other legacy project, in the neglected and disinvested Eastside neighborhoods near the city’s historic core, proposes catalytic interventions to create public spaces, transform streets, and improve the quality of the public realm. The goal of the Eastside project is to “promote public and private partnership, increase housing, enhance neighborhoods, create safer walkable streets, build parks, and offer incentives to businesses that wish to locate or expand operations in the neighborhood,” says architect and urban designer Dhiru Thadani, who led the consultant team for CNU.

Along with these projects, the city adopted a 2033 Downtown Plan, setting in motion implementation efforts aimed at improved quality of life in many neighborhoods.“The Legacy projects laid a lot of groundwork for what’s in the master plan,” says Eric Brown, an urban designer and architect who helped the Savannah Development and Renewal Authority (SDRA) to generate the visions. “Especially the southside project, which got a lot of people excited about planning and redevelopment in an area that isn’t downtown. Having the [CNU] congress here helped. The [planning and land use] environment is much different than it was three to four years ago, and getting the plan adopted is a result of that.”

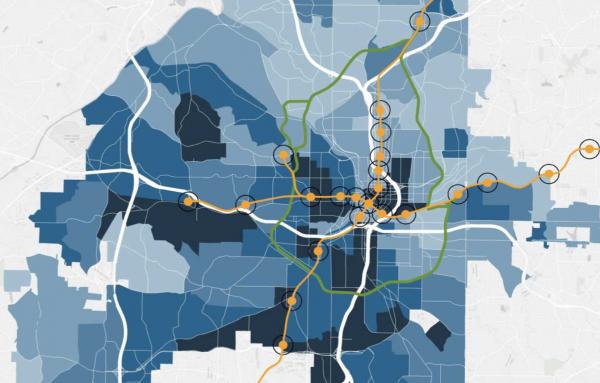

The plan outlines a series of big picture goals and low-hanging fruit for Savannah’s world-famous historic district and surrounding neighborhoods, comprising nearly seven square miles. “If undertaken in whole, it is estimated the Plan could provide a boost of $4 billion in real estate value, generating $41-55 million (in 2017 dollars) to the City’s bottom line,” the report says. SDRA has asked the city to use left over money from the planning process toward implementation, including a citywide transportation plan that would address how to make the city’s streets more walkable—among other issues.

The plan recommends substantial code reform—a position that the city already made progress on with a zoning update just a month before the recent action. The city’s antiquated zoning code made most of the historic downtown buildings illegal to build anew, according to Brown. The setbacks, building coverage, and parking requirements gave developers two choices: Building something suburban in character or get a slew of variances. The recent zoning update addressed many of these issues by reducing parking requirements and making infill development that matches the city’s character easier. Restrictions against accessory dwelling units were eased.

Yet the downtown plan recommends additional zoning changes, including those that would allow more “missing middle” housing. The city has been working with the Project for Lean Urbanism on a “pink zone” that could test additional zoning changes that would allow for missing middle, Brown says.

Suburban zoning standards were identified as a significant problem in Eastside legacy project, and the recent zoning changes will help significantly, Brown says. Many of the other ideas included public spaces that are lacking in the Eastside neighborhoods and taming corridors with speeding traffic. The city has already started with streetscape improvements along the Waters Avenue corridor.

Brown identifies two major next steps. One involves the reuse of the Savannah Civic Center site, where CNU held venues at last year’s Congress. When the Civic Center was built, one of Savannah’s famous squares was eliminated and the street grid was disrupted. Now that the Civic Center is being replaced by another venue, the city has a chance to restore the historic grid along with the square that was demolished.

The other is the citywide transportation plan, which would involve bringing in a consultant who is an expert in street transformation. Such a plan would be key to implementation of both Legacy projects, Brown says. The resolution to support the Legacy projects and downtown plan was approved in late September.