Creating Temenos: An experiment in suburban retrofit

“The catalog of forms is endless; until every shape has found its city, new cities will continue to be born.” ~ Italo Calvino

In an article early last year, I reported on the process by which Pierre L’Enfant designed the city of Washington, using various principles of what is known as “sacred geometry.” These mathematical and geometric concepts, including the Golden Mean (the ratio of 1 to 1.618) were fundamental tools for artists, designers, and architects going back thousands of years to the builders of the Egyptian pyramids, the Temple of Solomon, and the iconic buildings of ancient Greece. In fact, it was standard practice to use these ideas of proportion and ratio for any grand public building throughout most of western civilization, until the coming of 20th century Modernism. Rarely if ever to my knowledge however, were they applied to the urban layout and street pattern of entire cities, other than L’Enfant’s Washington DC.

What is this “sacred geometry” that L’Enfant knew of and employed? How might his approach be put to use today? L’Enfant’s intent was to design a city as an immersive environment filled with meaning and memory, reflective of political, cultural, and spiritual values. Our varied challenges today, including environmental degradation, societal and political fragmentation, and the various disasters stemming from suburban sprawl, are quite different from those L’Enfant faced. Yet his method of design holds great merit for us.

Sacred geometry

Though I was a mere C student in 10th grade geometry class, I have always had a fascination with shape and form. In my recent explorations of geometry, I have come to understand that, to the ancient world, geometry was not just a mathematics of engineering; profound spiritual meaning was ascribed to various geometric shapes, numbers, and mathematical principles. The term geometry simply means “measurement of the earth.” What moves it toward the “sacred” is its ability to make visible that which is invisible, to reveal the repeating patterns and forms found throughout the natural world and the universe. Geometry thus is the blueprint which god used in the creation of the physical universe.

To the ancient world, the number five for instance, as found in a five-sided pentagram, was representative of the earth and its people. The number six, in the form of a hexagon, of the gods and heavenly realms. In fact, it is said that the entrance to Plato’s academy of philosophy was inscribed with the words, “Let no one enter here who does not first understand geometry.” The medieval and Renaissance worlds continued the use as standard practice, as did the Victorian era.

The Flower of Life, a pattern which grows out of the Golden Mean (the ratio of 1 to 1.618), has been considered to be a sort of “DNA structure,” containing all the patterns and shapes of the universe. It is symbolic of the connection of all sentient beings to each other. It has been found in locations around the world, going back several thousand years, including the Egyptian Temple of Osiris and the Forbidden City in Beijing. Leonardo DaVinci studied it deeply and included it in his creations. Sacred geometry is thus both a practical tool of engineering and a contemplative process of spiritual understanding. Only with the coming of our current modernist values in the mid-20th Century did sacred geometry fall out of general knowledge and use.

L’Enfant’s design of Washington DC

When he was offered the task of designing the new nation’s capital city, Pierre L’Enfant took on the opportunity with the intent for the city pattern to act as the physical embodiment of the ideals found in the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the heavens above. He wanted to create an immersive environment in which one could be reminded of our highest political and spiritual aspirations, simply by walking down the street. As would any land planner, L’Enfant began work by surveying the land and analyzing the topography, making note of the high points and wetlands in the area. He spent an enormous amount of time getting to know every corner of the land he was given to work with. Following this he began a nine–step process of overlaying simple geometric forms onto the land, which determined the pattern of streets and location of significant public buildings such as the Capital Building, White House, and Supreme Court. Using the location of the Capital Building as a starting point, a series of circles and stars emerged out of his use of the Golden Mean; the sides of the stars formed the angles of grand avenues, while the underlying grid pattern grew out of the intersections of the angles and points of the stars. More on this process can be found here.

Sprawl repair and redevelopment

Finding the lessons and take-aways for today from L’Enfant’s achievement can seem a bit of an obscure effort. Our needs now are dramatically different from those of the newly minted United States. While our human goals and aspirations, political and spiritual, remain the same, the largest immediate challenges we face today revolve around environmental devastation, the wounds inflicted by suburban sprawl, and urban abandonment. Healing the physical damage we have inflicted on the natural world and the built environment, as well as the psychic hurts we trade with each other and our society, is our calling today. Within the professional world of urban planning known as New Urbanism, a central vision known as sprawl repair is responding to some of these needs.

Like an angry Old Testament prophet, the author James Howard Kunstler has declared that the sprawling pattern of American suburbia has created places not worth caring about. The general response these days is a call for “sustainability.” But what is it we are trying to sustain? The architect Steve Mouzon replies that true sustainability comes not from better technology nor even from a more fundamental change in values and lifestyle, but from “lovability.” Just as in our relationships with other people, if we do not infuse an effort with love, we will not care enough to maintain it and tend to it. Christopher Alexander, in his book The Battle for the Life and Beauty of Earth, echoes these sentiments. America is full to bursting with ugly, unloved places. Their repair, healing, and transformation must include an infusion of love, meaning, and memory. This is the role that sacred geometry can play here as a design tool; to show us the patterns of connection in the larger universe, by grounding us more firmly to the here-and-now, and remind us of our highest aspirations of common culture and personal psycho-spiritual journeys.

The transformation of suburban patterns of development into more traditional forms emphasizing mixed-use walkability remains controversial; many see the effort as overwhelming and unnecessary. Certainly, layering such vague ideas as “lovability” and shared cultural aspirations into the mix creates uncertainty and complexity. The commercial real estate market seems to be anxious for solutions, however. Shopping malls across the nation are closing as their anchor tenants, such as Sears and JC Penney, go bankrupt. Estimates are that hundreds of such regional and strip malls will close in the next few years. What is to be done with these failing and abandoned places?

An Experiment

While I was chair of the Lancaster City Planning Commission in central Pennsylvania during the early 2000s, representatives of the local shopping mall, Park City Center, asked for and were granted approval for various changes to the property. In the course of conversation, I offhandedly asked if they would ever consider converting the property to a mixed-use town center. A discussion never developed, but I held the desire for years to experiment with that idea. After completing the article on L’Enfant, the idea struck me to use his process and methods and apply them to the Park City mall property. The process by which L’Enfant designed Washington DC was dramatic and inspiring, and holds great vision, but these days we rarely get the opportunity to design from scratch on bare land without constraint. Rather, we must focus on the repair of suburban sprawl, environmental degradation and climate change, and the neglect of older cities. Park City Center represented an opportunity for me to consider how sacred geometry and L’Enfant’s design process can be put in service of sprawl repair and the healing of environmental and urban wounds.

To begin, the appropriate geometric pattern needs to be discovered and drawn upon for inspiration. Various aspects of sacred geometry present themselves for this purpose: the Golden Mean, Mandorla, Pi, the Flower of Life, and the attendant hexagonal honeycombs. Additionally, development work should always take into account local precedent and tradition. The local precedents appropriate to this locality include the Amish “hex” signs one often sees in the area. These have no real history other than decorative art. Although they occasionally include patterns reflective of sacred geometry, no meaning is ascribed to them by the Amish themselves. However, Lancaster County is known as the “Garden Spot” famed for its agriculture; so, while several approaches are possible, it seems appropriate to focus on the geometry of the Flower of Life and thus the hexagonal pattern of the beehive honeycomb.

Once this decision was made, I created a series of steps similar to those L’Enfant took, as outlined in The Sacred Geometry of Washington DC, by Nicholas Mann. (Note: The project as I undertook it encompasses land beyond the Park City Mall property, including commercial land across Plaza Boulevard, both within Lancaster City and Manheim Township.)

Step 1: Determine a central point of beginning. The obvious choice was the crossing point of the two existing axes of the shopping mall. The four existing “big box” stores are shown here; they will remain for re-use, while all other built elements on the site may (or may not) be demolished.

Step 2: Draw a circle, 618 feet in diameter. This represents the Golden Ratio of 1: 1.618. This circle roughly arcs through the center of each of the four big box stores.

Step 3: Draw a second circle of equal size, so that the edge of each touches the center of the other. This creates an oval, football-shaped overlap, known as the vesica piscis, or a Mandorla. This can be considered as the western equivalent of the eastern Yin Yang symbol. It is symbolic of the celebration and reconciliation of opposites. Early Christian iconography used it as a frame for Christ, and it is found in the architecture of Gothic churches and catholic imagery; it is also reminiscent of the “fish” symbol often used today by evangelical Christians. Psychologically and spiritually, the crossing of two entities, between their centers and edges, speaks to our universal connection with each other and all of creation. Where the two meet and cross over into one another, transformation occurs.

Step 4: Continue drawing such circles until a pattern known as the Seed of Life emerges. This is a pattern of seven circles, which forms the basis of the Flower of Life. Some consider the seven circles to represent the seven days of Creation.

Step 5: Continue the pattern until a field of flowers appears. This larger pattern is known as the Flower of Life, described earlier as a foundational pattern of universal geometry.

Step 6: Within each flower, a hexagon can be drawn, using the tips of each petal as an angle for the hexagon. Significantly for this project, the initial central hexagon fits amazingly well within the area formed by the four “big box” stores. Two sides of the hexagon align almost precisely with two building facades, while two angles of the hexagon are located at the approximate center of the other two buildings. This result, an unexpected synchronicity, confirmed to me the appropriateness of this pattern for the redesign of the site, in much the same way L’Enfant must have felt when seeing his circles spanning precisely from Capitol Hill to the Anacostia River.

Step 7: Continue drawing hexagons. A beehive pattern emerges. Bees use a hexagonal arrangement in building hives, as this shape is both strong and efficient. As mentioned earlier, Lancaster County, with its strong agricultural heritage, is known as “The Garden Spot,” making the beehive an appropriate symbol and pattern for this project. Moreover, each hexagonal cell can be considered as the basis for individual neighborhoods within the town center as a whole.

Step 8: The points and intersections of the hexagons, and the centers of the flowers, shown here as red dots, are then overlaid on the site. They designate potential locations of significant elements of the design or “points of memory and inspiration,” such as squares, fountains, sculptures, monuments and significant buildings, the alignment of streets and pathways, terminated vistas, and prominent sites for civic structures and activities.

A skeleton of sacred geometry is now prepared, around which the body of a town center can be laid out. At this point, I transition to fleshing out this skeleton with a set of New Urbanist design and policy tools. These include an emphasis on compact pedestrian life, street design, and fine–grained mixed uses.

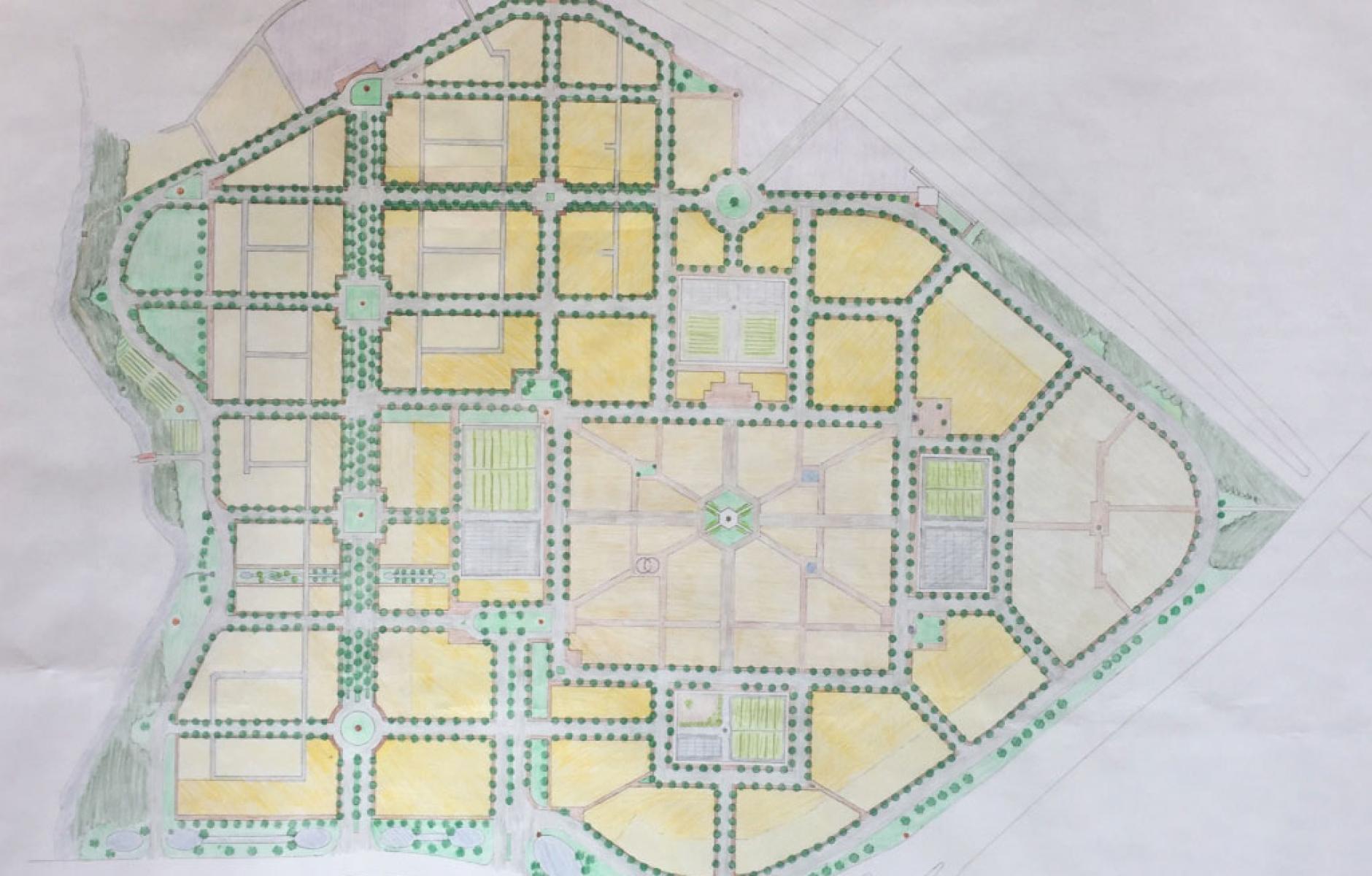

Step 9: The site plan emerges. Seen here overlaid with the honeycomb pattern, the street pattern and arrangement of blocks are based upon the location of the geometric points. Some pre-existing elements in addition to the four “big box” structures are preserved, including the approximate locations of entrances onto the site, and the alignment of the loop road. To the greatest extent possible, visual lines of sight are to be maintained between the points, both for ease of orientation and so that a sense of an immersive environment can be created; that is, one feels a sense of being in a central place of special significance, surrounded by memory and meaning.

Mixed-use projects such as this have long included residential, shopping, and office space. Today, there is a societal shift away from shopping to “acquire things” toward a desire for “experience,” adding a new element to the mix, that of entertainment. Yet the inclusion of meaningful cultural and civic life is still almost nonexistent other than parks and open space. Providing a civic heart, places that can evoke meaning and memory, remains the missing amenity. The “points” that the geometry provides are meant to fill that gap; not to promote any particular approach to religion or spirituality, but to express those elements of civilization that find their source there. This comes in the form of celebrating local history, writers, poets, artists, musicians, inventors, and so forth. These are designated in a number of ways; parks, small fountains, trees, sculpture, monuments, outdoor stages, cultural institutions, and so forth; places where we can share our personal and collective stories, and create new ones.

The final site plan shown at the top and end of this article reveals a full community. This includes a variety of residential types, large and small retail space, offices, artisan workshops, parks and open space, and provision for civic uses. The four remaining “Big Box” outlets are imagined to be reused in the historic mixed-use pattern of classic multi-story arcade buildings such as Westminster Arcade in Providence RI or The Arcade in Cleveland OH. Each is topped with green roof gardens, solar electric and hot water generation, and other elements of sustainable technology. Two of the points of meaning and memory are located with these mixed-use arcade buildings.

The central area surrounded by the big boxes—what currently constitutes the indoor mall—is envisioned as a mixed area of small buildings fronting onto intimate pedestrian streets. Examples of such spaces are seen in the images shown here. On the east side of the site, currently a parking field, is envisioned a small senior living community, patterned after what is known as a “Begijnhof,” a semi-cloistered medieval urban form.

The estimated uses for the entire project include:

- Residential: 1,500 units (townhouses, condominiums, apartments, retirement “Begijnhof”)

- Commercial: 1,400,000 square feet (retail, office, dining, artisan)

- Open Space: 20 acres (parks, gardens, playgrounds, plazas)

- Parking: 7,400 spaces (on-street, structured, underground)

Civic life, as expressed in the various points of memory and meaning, can be found in a number of ways in this plan. They are included both as larger places of public gathering and more quiet spots of private reflection. There are twenty-three such points on the plan. What might they look like? A few examples include:

1) A central tower and plaza placed at the center of the first circle. It constitutes the heart of the community, and functions as the central gathering place and main focal point.

2) The entrance to a community garden, located within the linear park along the Little Conestoga Creek, is visible as a terminated vista at the T– intersection of a street.

3) Two of the points are located within the interior of the reconfigured big box arcades. These might take the form of a sculpture or fountain

4) A children’s outdoor stage, which might be located in the riverfront linear park

5) The series of squares along the main boulevard, are reminiscent of the various squares of Savannah

6) The northernmost Point terminates a street and lies adjacent to the railroad tracks. It might be configured as a water park similar to that found in downtown Lancaster’s Steinman Park

A "point" may consist of something as simple as a small sculpture along the sidewalk, perhaps dedicated to a local artist or musician; Charles Demuth is an appropriate example for Lancaster.

Although many projects include such features, they are often afterthoughts. While perhaps quite well done, they may not add up to something greater. This experiment seeks to make these civic elements the primary “skeleton” around which the community is structured. Using Sacred Geometry to form the urban pattern, as well as to experience the place as a pedestrian, is similar to the way in which the drawing of a mandala, or walking a labyrinth, acts as a form of reflection and meditation. This not only grounds the place as significant and meaningful in people’s everyday lives, but can add value to properties nearby or fronting onto them, and also creates places in which people—residents, workers, and shoppers—want to linger. The practical and the aspirational are both enhanced.

Creating lovable places of “meaning and memory” is the goal, but such a huge undertaking has to be financially viable to the developer. How does this effort fare financially to the property owners, and to the city fiscally? A full-blown financial pro-forma is beyond the scope of this little experiment, but a quick comparison of appraised value with the properties in the Downtown Investment District (DID), which is approximately of equal size, can give some indication. Park City Center is assessed at $1,602,062 per acre. Properties within the Lancaster DID are assessed at $2,826,373 per acre. The fine-grained, mixed-use pedestrian pattern seen in the DID holds 76 percent more assessed value than the suburban model of Park City Center on a per-acre basis. Thus, while the costs associated with demolition and redevelopment are enormous, when done incrementally over time the effort appears very worthwhile. More information on the fiscal and financial impact of such a comparison can be found here.

This plan and its process was presented to the mall owners, Brookfield Properties, this past summer. While the response was generally positive, this design would involve such an enormous and costly effort that Brookfield was clear that the only way forward is a phased renovation over the course of several years, rather than an all-at-once effort. Even with the increasing number of anchor tenant bankruptcies and vacant storefronts, the mall still creates enough cash flow to warrant continued use for the time being. Lancaster City leadership was informed of the effort as well. At this writing, Brookfield has approached the City with a request for demolition of one of the empty “big box” stores, with the intent of developing a series of stand-alone structures. The transition to an unknown future is underway.

The term Temenos, the title of this article, is an ancient Greek word designating the sacred ground or plaza in front of a temple. Given our needs today, we must begin to think of the entire city in this manner. In his book City and Soul, the Jungian psychologist James Hillman reminds us that Spirit is not only embodied in us and the natural world but in human artifacts as well. This is why art moves us so deeply. Urban settings, whether grand City or small town, are the greatest artifacts we create. Our understanding of them, and the role we ask them to play, must be dramatically expanded. Given what we face now, psychically, politically, and environmentally, this is essential.

Think of cities and towns as schools or classrooms. As spiritual beings, temporarily here on earth as humans, we are essentially students in boarding school. The natural world of planet Earth is our home and foundation; our urbanism expands and builds upon this, both physically and metaphorically. The physical places in which we locate ourselves therefor have a significant impact on our opportunities for psychological and spiritual growth. If this physical world is the “schoolhouse” to which we are all sent, we have a large responsibility to provide the most advantageous, well-organized and supplied classrooms possible. This means creating places of grace, beauty, memory, connection and interaction.

The places we build reflect the values we hold. We must finally move beyond thinking only of the practical to envision lovable places of meaning and memory. Sacred Geometry provides a crucial tool, both physically and psychically, for us to expand the sacredness of Temenos to include the entire City.

This article was published on the blog The Urban Evolutionary.