Best practices for ending exclusive single-family zoning

Last year was a groundbreaking one for housing policy and legislation to enable Missing Middle Housing across cities and states. Minneapolis adopted a policy to allow up to three units on any lot, even those zoned for single-family. Oregon passed HB 2001, effectively eliminating exclusive single-family zoning statewide and enabling a range of Missing Middle housing types, allowing up to two housing units on every residential lot within cities (and up to four housing units in cities with 25,000 or more residents). The current version of California’s proposed SB50, although largely focused on development around major transit, would allow up to four units on single-family lots in geographic areas that meet certain criteria.

What these efforts illustrate is that using Missing Middle Housing can go a long way toward meeting housing needs in a variety of places. There are two important parts of this message:

- Incrementally increasing the allowed number of units/densities can substantially increase the number of housing units and address housing costs (see note below regarding using density/number of units carefully);

- Higher densities do not have to equate to larger buildings: House scale buildings/Missing Middle Housing can accommodate more units, more choices, and higher densities.

Here are six tips to effectively guide the evolution of single family neighborhoods into Missing Middle Housing neighborhoods integrating duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes. Many of these seem very basic, but are typically overlooked, and they do make a big difference in delivering high-quality results.

1. Regulate maximum building envelope/form & scale rather than number of units/density

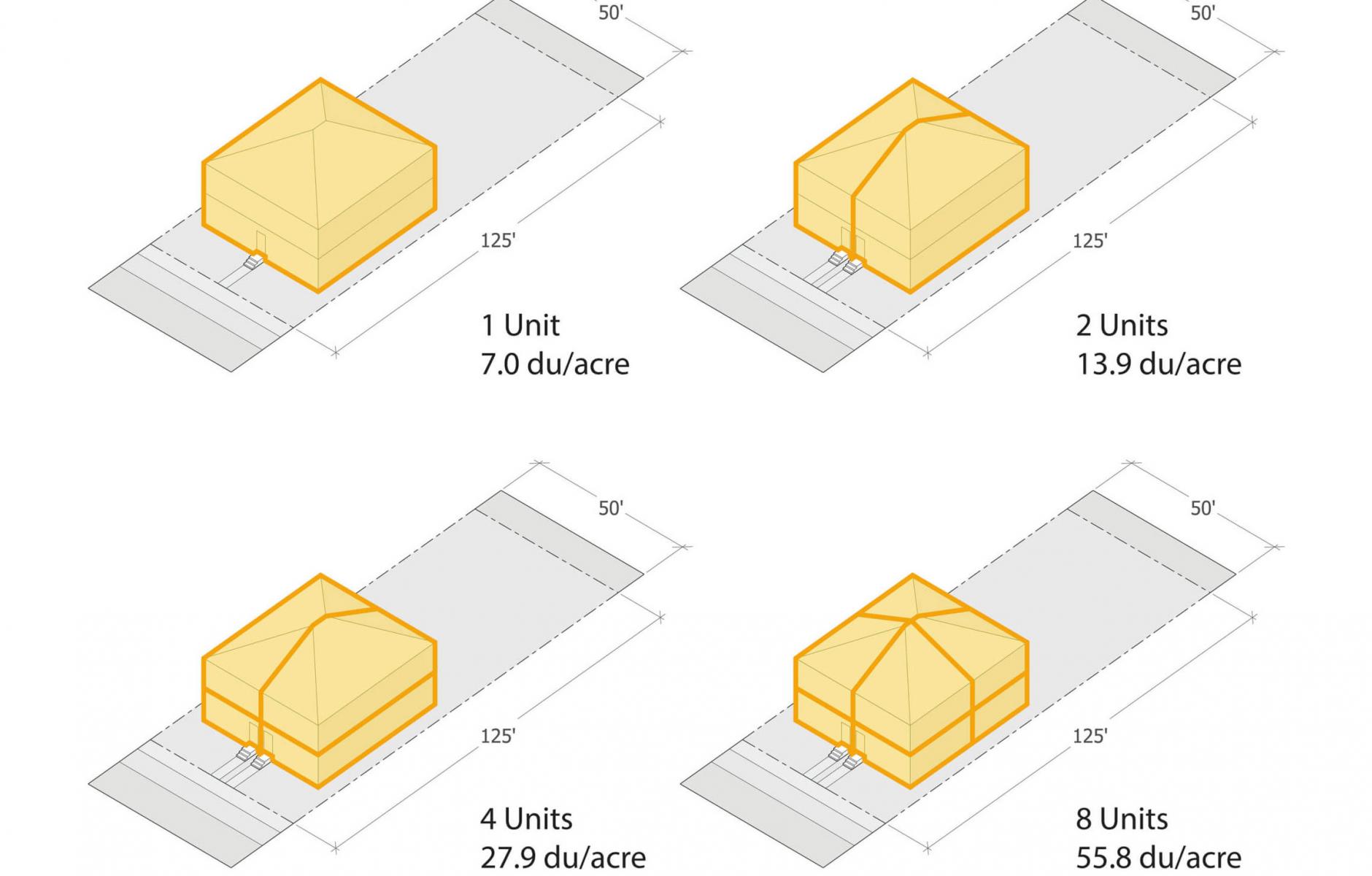

Most cities, policies, and bills focus on the number of units allowed on a lot. The good news about this approach is that after it is adopted it will increase the number of units compared to single family homes, but the bad news is that it will likely result in the delivery of the largest, most expensive/least affordable units that a builder can fit onto the site. How do you prevent this from happening and deliver more attainable options? Instead of defining a maximum number of units in policy, legislation, or zoning, define a maximum width, depth, and height (i.e. an allowed building envelope) that can be publicly supported, and allow any number of units within that defined envelope or form (see image at top).

For example, if you regulate to allow a building that is a maximum of 50 feet wide, 55 feet deep, and two stories tall, you are allowing a 5,500 square foot building. If you define the maximum form and not the number of units, your policy and regulations would allow for a builder to deliver this as two 2,750 square foot units, four 1,375 square foot units, or eight 688 square foot units within that same allowed building envelope. Obviously, the 688 square foot units are going to be more cost-attainable than the larger units. If regulations/policy cap the number of units (as density has done in the past), it discourages smaller, more affordable units.

2. Carefully regulate building width and depth

This sounds very basic, but very few zoning codes directly regulate the size of a building envelope (form) with a maximum width and depth in addition to maximum height. This is important to deliver predictable built results. Setbacks and FAR only deliver predictable scale and form when lot sizes stay consistent, which is rarely the case in most neighborhoods. Height is typically regulated, but if a maximum width and maximum depth are not regulated and one lot is bigger than the one next to it, or if a builder has aggregated lots, the built result on the larger lot will be out of scale with its neighbors.

Maximum building width and maximum building depth need to be regulated in addition to height for predictable results. Image by Opticos Design.

Committing to this maximum scale of allowed “container/building envelope” is a great way to build support from community members for Missing Middle housing, because delivering more units does not have to mean larger buildings. Missing Middle types achieve more units, with higher densities (sorry, I had to use the D word!) within house scale buildings.

3. Be careful about allowed height

Ideally, Missing Middle Housing is no more than 2.5 stories in height to keep it “house scale.” Remember that Upper Missing Middle Housing, which is 3-plus stories, is still very relevant and necessary, but it should be considered a separate classification—and applied to different geographic locations—so as not to confuse the conversation or compromise support.

How is height measured in your zoning code? A maximum height measured at an eave will produce very different building forms than a maximum height measured from the highest point or even as an average height. If your heights are measured to the highest point, rather than to the top of the eave or parapet, your zoning may be encouraging/incentivizing flat-roofed buildings which likely will not be in character with existing structures.

4. Do not allow townhouses or single-family detached homes in which the ground floor is mostly parking

In most markets, if regulations allow, developers will deliver multiple “tall, skinny” single-family detached homes, or “tuck-under” townhouses (in which the ground floor is mostly parking with two-stories of living space above). You need to carefully consider and decide if the delivery of these housing types will meet policy intents, such as affordability goals, and the desired form and scale outcome. In some contexts it may, and in others it may not.

There are two issues with allowing these types:

- They do not deliver a good level of affordability, even compared to the single-family home they are replacing. A recent study by the Brookings Institute demonstrates that tearing down a single family home and replacing it with townhouses delivers more housing, but does not deliver more affordable prices in the same way that delivering a multiplex does. The study was done on a 4,500 square foot lot in the Washington D.C. metro, and compared prices of an existing single-family home purchased for $1,000,000 to redevelopment of the site with either three townhouses or a six-plex condo building. While each of the townhouses would need to be sold for $999,000 to support redevelopment, each of the six condos in the sixplex would need to sell for only $579,000, a substantially lower and more attainable price point.

- The tall, skinny single-family homes and tuck-under townhouses do not typically deliver good urban form. Issues include ground floors occupied almost entirely by parking, low quality/minimal shared or private spaces, and excessive development of rear yards—causing privacy-related issues and eliminating the “green middle block” that even very urban neighborhoods in Brooklyn, San Francisco, and London have. Many downtown-adjacent neighborhoods in Houston are suffering from low-quality infill of these types that decreases the walkable urban quality of the neighborhoods.

5. Some single-family contexts are better than others for Missing Middle housing

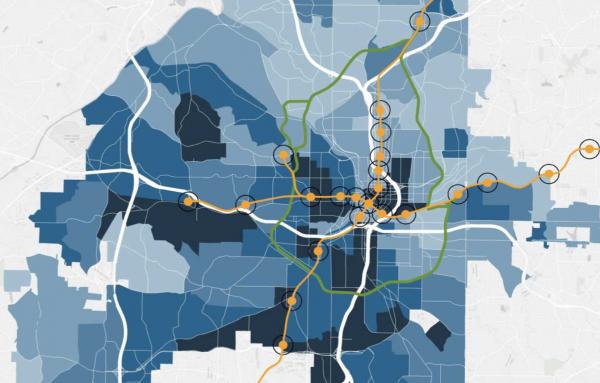

Not all single-family contexts are as equally well-suited for Missing Middle Housing application. One of the main reasons that it made sense for Minneapolis to allow triplexes citywide is that a large majority of the city was laid out in a pattern of walkable streets and blocks with a mix of housing types prior to World War II. It does not hurt to enable Missing Middle Housing in more suburban/auto-dependent locations, but outside of creating complete new walkable neighborhoods in these contexts, it is less likely that builders will start building Missing Middle Housing or converting single family homes. This is because the market segments looking for Missing Middle Housing are not typically looking to live in auto-dependent places, and the economics are not likely in place to encourage this.

6. Communication and framing tips

Here are a few tips to frame the conversation for a broader range of housing choices in your community:

- Avoid conversations about increasing density. Instead, focus on increasing housing choice and attainability. I often recommend that we stop using the scary “D” word altogether because you will never convince any neighborhood that increasing density in and of itself is a good thing for their neighborhood. Consider terms such as Missing Middle Housing, house scale, housing diversity, and housing choices rather than density.

- Document and photograph local examples and make this information easily available. This seems simple, but very few cities have done this. Having a series of photo boards and/or an easily-accessible online collection of examples makes it easier for people without technical knowledge to relate to the planning, policy, and zoning decisions needed in order to permit these types. Simply photographing and documenting other physical characteristics of Missing Middle types (see example here on missingmiddlehousing.com) is a great first step for any community. This is often the first step of a Missing Middle Scan.

- Personalize the conversation and tell stories: Who has lived in one of these types? Who is currently living in these types? Whose kids or other relatives are living in one of these types? How are Missing Middle types beneficial for downsizing Baby Boomers? How are these types important for improving viability of neighborhood main streets and the coffee shops, restaurants, retail shops, etc. that are such a desired amenity in these neighborhoods? In order to take away some of the perceived stigma and help build support, form stories about who this housing will be for and who it has been for in the past.

There are many other barriers to Missing Middle Housing. One big barrier: onerous construction defect liability laws. These disincentivize and often prevent for-sale Missing Middle buildings from being built at all, because the inherent risk is not justifiable for small-scale builders. Another barrier: development fees that are charged per unit, regardless of whether the unit is 500 square feet or 5,000 square feet. This decreases the feasibility of small units.

Note: Dan Parolek’s book, “Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to the Housing Crisis,” is now available for pre-order from Island Press and will be available in late spring of 2020.