How a brutalist building is reviving a mid-sized city

Note: CNU cosponsored a Public Design Charrette in the Seneca One tower, under renovation in Buffalo, in late February.

In 2007, Harvard economist Edward Glaeser wrote an article with an blunt headline that answered its own question: “Can Buffalo Ever Come Back? Probably not—and government should stop bribing people to stay there.”

The article explains long-term changes in transportation and industry leading to Buffalo’s decline—the Erie Canal made the city the largest grain port in the world, but those days are long gone. The author criticized government-subsidized investments like the 40-story Marine Midland Center (now called Seneca One Tower), the tallest and largest building in Western New York, which failed to slow the city’s descent.

The 1970s fortress-like brutalist building is an example of poorly planned urban renewal, creating pedestrian-unfriendly frontages and literally windswept plazas (Seneca One spans Main Street and creates a tunnel that amplifies prevailing winds from the lake) on two full city blocks. In Glaeser’s view, the design didn’t matter—he even described the building as a “splendid waterfront edifice”—it has beautiful views of the lake, although located several blocks away. Investing in Buffalo as a place, Glaeser argued, is just throwing good money after bad.

The article was published just prior to the Great Recession, which dealt a savage blow to the nation’s economy, and weaker cities like Buffalo were especially vulnerable. Seneca One tower was nearly vacant by 2014, 40 years after opening. In 2017, prominent urban theorist Richard Florida named what he called “winner take all urbanism,” in which wealthy cities like New York, Boston, DC, and San Francisco attract all of the talent that is key to 21st Century prosperity, and lower-tier cities like Buffalo languish.

The blunt 2007 assessment would appear to be on target—with the small exception that Buffalo is now clearly coming back economically and culturally as a place to live, work, and visit. New businesses are locating downtown, historic buildings are being renovated, new buildings are under construction, and amenities are making the city core attractive once again. Downtown is reinventing itself as an entertainment, lifestyle, and 21st Century business center. The change is apparent to anyone who has visited the Buffalo recently compared to, say, a decade ago. Against all expectations, Seneca One tower is poised to become the most dramatic story of that revival.

New life for Buffalo's tallest building

DC-based developer Douglas Jemal purchased Seneca One for $12.6 million in 2016, a decision that raised questions about how such a huge, vacant building could be leased in a place like Buffalo, with no shortage of vacant properties. Surprisingly, Jemal then proposed to add to the building’s 1.2 million square feet by filling in empty spaces around the tower with new buildings to create active frontages on surrounding streets. The vision turns a massive liability to an asset for urban life.

To raise the degree of difficulty, Jemal proposed significant new retail development. Nobody has tried that since Buffalo’s retail began a “death spiral” in the mid-1980s—losing a slew of department stores and the smaller shops that depend on those anchors.

The project also includes modern, large-floor-plate Class A office development. Jemal proceeded to land the largest office deal that the city has seen in recent memory. M&T Bank, Buffalo’s biggest private employer, is establishing a technology center in Seneca One that will bring 1,500 new jobs downtown—some of which are being imported from the suburbs. The building also hosts 43North, a tech incubator with a half dozen startups. Each new tech job will create an average of five ancillary jobs, according to Brendan Mehaffy, the city’s executive director of strategic planning. Three of those ancillary jobs will be available to people without a high school education, he says.

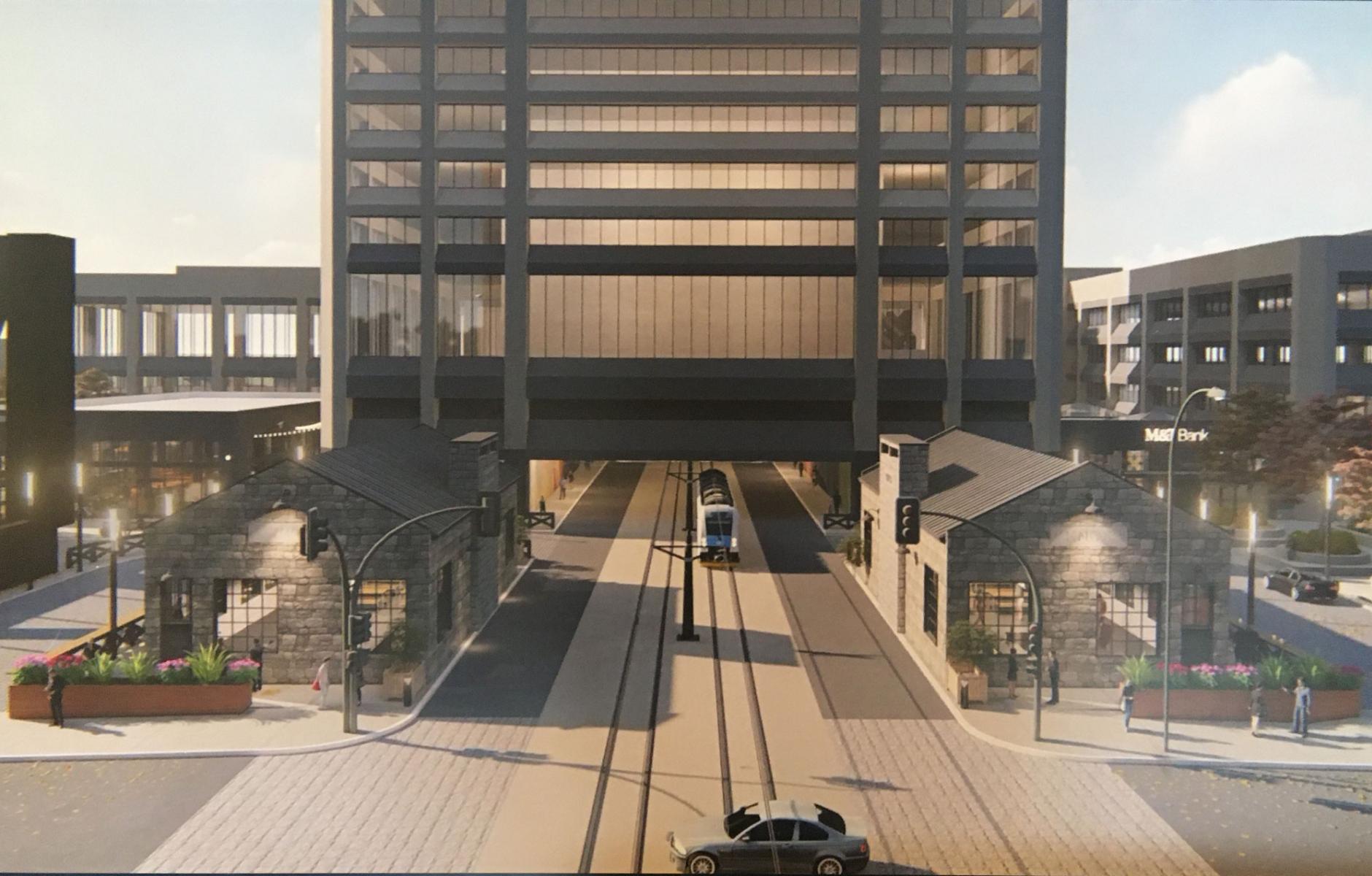

Overall, Jemal is turning Seneca One into a mixed-use development featuring more than 200 residential apartments and office space in the tower. The 3.5-acre concrete plaza area and east annex will be redeveloped into a 75,000-square-foot, multi-level retail center, with a variety of outdoor seating (see rendering above). Two buildings have been constructed on the plaza to support street-oriented retail—and in other parts of the complex the basement level will be renovated to activate the street, Two more small “clubhouses” are under construction for bars and entertainment at the corner of Main and Seneca streets. Built of stone blocks, the clubhouses have a historic look even before they are completed (see rendering at top of article). The tower’s west annex wing will consist of 100 apartments, with a mixture of market-rate studio and one-bedroom rental units, as well as two-bedroom apartments. In February, Jemal reported that he is negotiating with a brewery as a lead retail tenant.

The project was eligible for $15 million in tax breaks—and the developer is foregoing that benefit to help the city fund a better public realm. “He was the first developer in modern Buffalo history to give up tax credits to the extent that he has,” says Mayor Byron Brown. Jemal has negotiated an innovative payment-in-lieu-of-taxes (PILOT) agreement to support an “Infrastructure Accelerator District” for improvements in the downtown area, including restoring automobile traffic on Main Street to share the space with light rail, and, in the process, update the design as a pedestrian-friendly, slow-speed street. When the rail line was built in the 1980s, Main Street was made car-free downtown (car-free may work in San Francisco, but it killed retail in Buffalo). Buffalo has been restoring Main Street car traffic on a block-by-block basis, but the city failed to secure a key federal grant to continue the work. Jemal stepped in.

The location of 1,500 new tech jobs in Buffalo calls into question the narrative presented by Glaeser and Florida on the future of second- and third-tier cities. In 2020, walkable urbanism and culture attract talent, and talent is a primary driver of economic development. While I was in Buffalo recently, the founder of one of the Seneca One tech startups—Numaan Akrom of a bus rideshare firm called Rally—said that he can’t afford to hire programmers in New York City. The talent in Buffalo is more affordable, he says. So maybe cities like Buffalo have the right combination of assets and affordability to drive economic development in the 2020s—and it takes visionary developers like Jemal to kickstart the process.