Riverfront visions transforming the Twin Cities

Both Saint Paul and Minneapolis are river cities, linked historically to mills and barge traffic on the Mississippi, and they are reclaiming a significant portion of the riverfront for public space and economic development.

Most of the public space in both cities is on the Mississippi or waterways that flow into the river. In the Twin Cities. The river was first a transportation/industrial corridor, housing was built close to the river that flooded and had to be removed, much of the industry died, the polluted river was cleanup up, and now public space and housing are appropriately sited on the river.

Both cities have big plans underway to transform sections of the riverfront. These plans were explained at CNU 28.A Virtual Gathering, which was planned originally as an in-person Congress located in the Twin Cities prior to COVID-19.

Saint Paul on the Mississippi

Saint Paul’s plan for 26 miles of riverfront, adopted in 1997, is one of the most ambitious river plans anywhere in the US. It has become an armature for development and public space in the city ever since. The city’s riverfront has become a more appealing place as parkland and trails have taken over obsolete industrial space and scrap yards, notes urban planner Ken Greenberg, who worked with the city, citizens, and private sector on the plan.

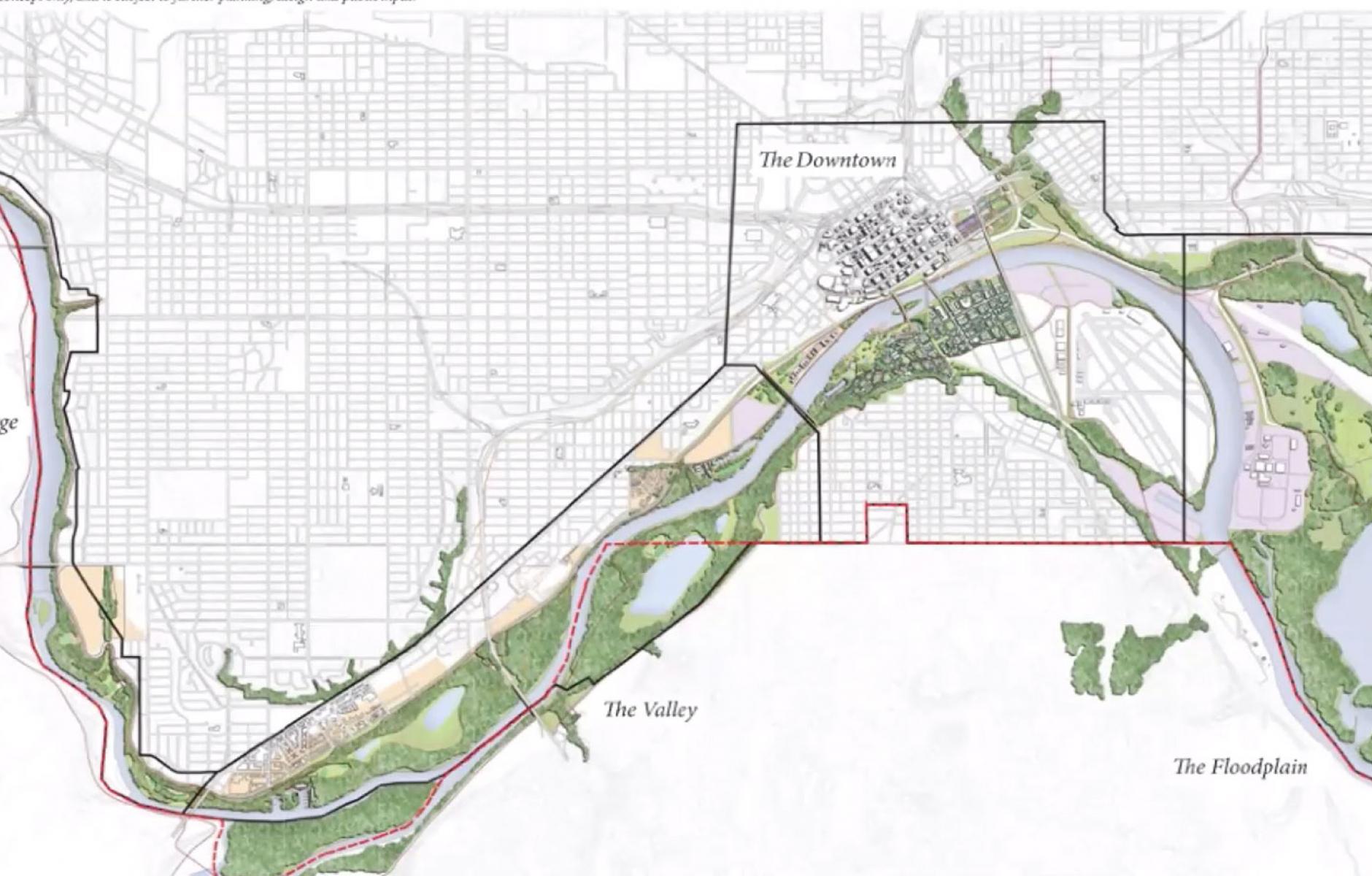

Greenberg noted of 35 public and private initiatives, including developments, that were moving forward in the mid-1990s—and they were linked in the plan via the connective glue of an improved public realm. Next, neighborhoods connected to the river were mapped, each with a community hub, and the collection of neighborhoods would form the city (see image above). The vision offered a powerful image of how the city would develop, and a high-profile rendering appeared on government and private sector letterheads. The plan captured the imagination of many citizens, and that helped to maintain momentum years after it was adopted. After the plan was adopted, city planning staff conducted detailed neighborhood development plans to allow development to take place and the waterfront to be transformed.

A gateway was created for the river, adjacent to downtown and a new science museum that “cascades” down the bluff (see photo above). A park lines the river in front of new development. This kind of connection to the river has been happening on both sides, in the vicinity of the downtown area, Greenberg says.

The vision continues to evolve and be implemented in new ways. The city now has a plan to connect green spaces along all 26 miles of the river and connect the river to the neighborhoods, notes Lucy Thompson, former city planner and long-time CNU contributor. In downtown, where the city is elevated on bluffs (and a freeway and railroad tracks run on the river flats), the city adopted the vision of a 1.5-mile-long “balcony” overhanging the bluff slopes.

“In some cases, this balcony connects to adjacent development, and serves as an amenity to private development, in other cases it is just an elevated pathway,” Thompson says. The pathway includes gathering spots and venues for music performances. The vision captured the enthusiastic attention of Saint Paul, she adds.

On the West Side, across the downtown. New development is opening up adjacent to a levee. The levee was built with an esplanade that has been widened. There is outdoor seating, outdoor events, and different ways to get down to river. In Saint Paul, the river is conceived as a place to add real value to the city in terms of health and the economy.

RiverFirst

The RiverFirst Initiative builds on landscape architect Horace Cleveland’s vision for the “Grand Rounds” as an interconnected park system for Minneapolis, linked by a parkway, notes Tom Evers of the nonprofit Minneapolis Parks Foundation. The northern riverfront—the site of pre-existing industrial and railroad infrastructure—was left out of this vision. “When complete, RiverFirst will link North and Northeast Minneapolis to the river through parks and trails for the first time in the city’s history,” Evers says. North Minneapolis is home to much of the city’s black population, and those neighborhoods are cut off from the river by industry and a highway, he adds.

The downtown waterfront was largely industrial, then blighted, and now has new residential, museums, and commercial uses. A new riverfront park is now being built to open this fall. A restaurant, Sioux Chef, will provide an amenity and generate activity in the park, honoring the city’s Native American heritage and focusing on indigenous culture.

Twenty Sixth Avenue stretches across North Minneapolis, but it lacked a good connection to the river. Now there is a dedicated bikeway and the city is looking at ways to bring people in North Minneapolis to the river in ways that represent African American history, Evers says. One idea is to create an overlook and connect to a river trail.

People in North Minneapolis are hungry for parks, says Kate Lamers of the Minneapolis Parks and Recreation Board. Green space and parks will help to address health disparities, she says, but the city is mindful of what she calls “green gentrification.”

While better parks are very much needed, “we understand the concerns that residents have that if they get a better park, and the land prices rise to the point that residents are pushed out, we have not, necessarily, served the equity goal,” she says.

The Parks and Recreation Board is looking at a “Just Green Enough Scenario,” she says. The idea is to provide amenities while making sure there is a larger strategy to protect community members. “We want to be part of that larger strategy,” she says. “If we need to, we are willing to modify and slow down the park design until people feel comfortable.”