Every traffic projection is wrong

Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from Chapter Six of Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: Transportation for a Strong Town, the latest book in the Strong Towns series. It has been slightly modified for this space.

The goal of traffic modeling is not to be right; it is to create a plausible narrative as to why more construction is both needed and helpful.

This sounds deeply cynical, and I hate writing it because there are good, decent, and honest people who do traffic modeling. There are also good, decent, and honest people who consult astrological signs to predict how a marriage will work out. Conviction in one’s predictions does not make them any more accurate.

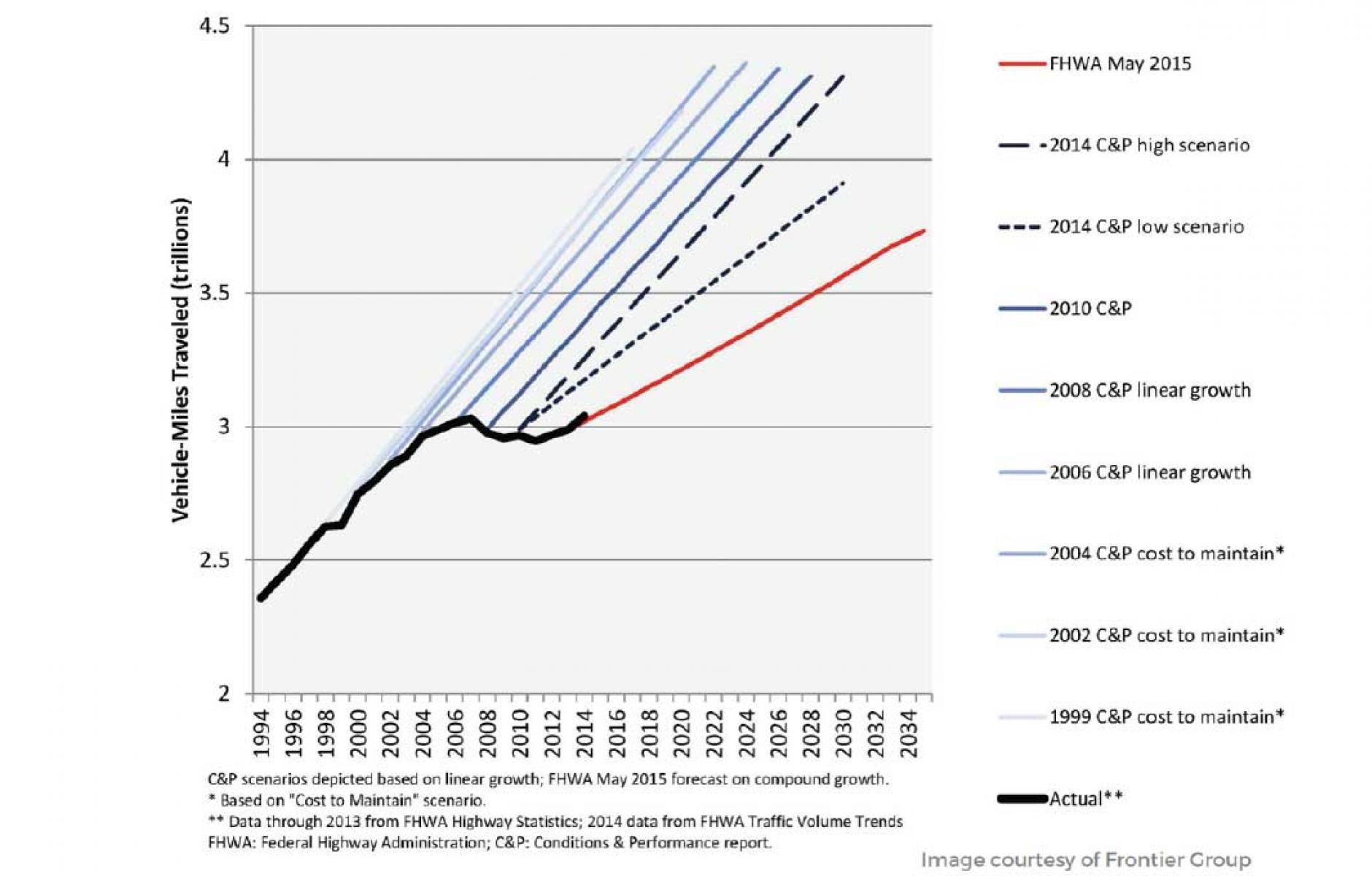

To be proactive in heading off congestion, or at least to create the appearance of being proactive, traffic engineers monitor the amount of traffic that currently travels on a road or street and use that data to project how much traffic there will be in the future. They routinely use projections of future traffic to make recommendations and decisions on transportation investments, spending that amounts to hundreds of billions of dollars each year.

Most projection models rely on linear, straight-line projections of past traffic counts. While the engineer doing the work may use a spreadsheet or modeling software that gives the result a veneer of sophistication, it is really no more complicated, and no more precise, than taking a ruler and drawing a best fit line through past data out into the future. There is no attempt to capture any emergent reaction from a dynamic system.

There are other approaches that attempt to consider dynamic factors when projecting traffic. While millions, perhaps billions, are spent nationwide each year, creating the illusion of sophistication around these various models, they are no better at predicting the future than the straight-line projection with a ruler. In 2015, Congress commissioned a report through the National Academy of Sciences that reached the same conclusion. From the report:

The committee concluded that existing [Travel Demand Forecasting] models do not offer the national- or regional-level prediction capabilities needed to assess system level impacts from Interstate investments.

That is a long way of saying that the models do not work. Of course they don’t. There is no way a model could capture all of the dynamic changes happening with individual decisions, choices that change and adapt in real time based on an infinite number of factors. Later in the same paragraph, the report states:

Because there are no existing tools with which to analyze these demand responses at the transportation network level for the entire country or regionally, the only alternative was to consult the recent history of travel behavior as indicated by past [Vehicle Miles Traveled] growth rates to develop a reasonable range of future [Vehicle Miles Traveled] growth rates to apply to the…models.

“Consult the recent history of travel behavior” is engineering-speak for plotting past traffic data on a chart. “Develop a reasonable range of future VMT growth rates” is a sophisticated way to describe the simple process of projecting the future traffic by applying a ruler to past data. Cities and states spend enormous sums of money doing this work, yet a competent third grader with a straightedge could predict just as well.

Sometimes, the historic data is supplemented with what are called trip generation models, an estimation of how much traffic should be anticipated based on what is proposed or expected to be built in a specific location. For example, if someone is building a restaurant, a traffic engineer or transportation planner may examine a chart or table suggesting, based on past observation, how much traffic a restaurant of different sizes can be expected to generate.

Of course, even though it has more effect on traffic than any aggregate study of restaurants, the transportation professionals have no way of taking into account whether the head chef will be amazing or terrible, whether the restaurant will become known for its great breakfasts or exquisite dinners, or whether it will fail in six months or have people lined up around the corner.

Even more importantly, the engineer confidently predicting future traffic flows has no clue as to whether this restaurant will be just the thing the neighborhood needed to become the next hot place, creating a feedback loop that draws all kinds of people in their vehicles to the area, or whether the restaurant will become the kind of obnoxious establishment near which others do not want to locate, depressing traffic throughout the neighborhood. Again, factors far beyond any spreadsheet or chart of expected values will determine the actual amount of traffic.

There is no way for the transportation engineer to know these and other dynamic reactions because they are not knowable. Instead of accepting that fact and developing an approach to traffic management that does not rely on false projections to provide an illusion of certainty, people who do traffic modeling tend to respond to the unknowable by making their models more complicated. This has the effect of creating even more separation between those who would challenge the model’s conclusions and those who can understand the methods used to reach them.

The opacity of the models reinforces a power dynamic that is central to the purpose of modeling. It is not the goal of a traffic model to predict the future flow of traffic accurately. That is impossible. Even though the person doing the modeling likely believes their own results, at least enough to bet other people’s money on them, the goal is nearly always simply to justify more investment in transportation.

The reality is that it is widely known within the engineering profession that all traffic models are wrong. The conscience is soothed because the profession always seeks better models, and a partially informed guess is perceived to be better than a completely ignorant guess. This known error is accepted because, for the traffic engineer, there is no viable alternative.

That is wrong — there is an alternative — but follow the reasoning because it points to a deeper insight. If the traffic engineer is forced to use a projection of future traffic that they know is wrong, and if congestion is an intolerable condition that is also a ubiquitous foe, then the conservative thing to do when considering a transportation investment is to oversize everything.

It is vastly more expensive to fix congested arterials than it is simply to oversize them to begin with. For an engineer, a conservative approach is not one that reduces the size and budget of the project, opting for a more incremental solution. No, a conservative approach means massively overbuilding everything under the guise of penny-wise, pound-foolish.

For the driver, who pays but a tiny fraction of the cost of any roadway they travel — and even that is paid indirectly — the gain from overengineering is obvious: open roads, free-flowing travel, and a high degree of satisfaction with the transportation system, at least until dynamic responses make claims on that excess capacity.

If the engineer were to err in the opposite way, if they were to under-design even a tiny amount, the hierarchical network would create intolerable levels of congestion. With this asymmetry, most transportation professionals find it better to have double the needed capacity and not use it than to suffer the consequences of being 5 percent short.

This propensity has generated some noted absurdities, including many examples of engineers projecting increasing levels of traffic on roadways where traffic volumes have been decreasing for many years. One of the most egregious is the SR-520 bridge across Lake Washington where the Washington State Department of Transportation three times over 17 years projected massive increases in traffic. Traffic volumes decreased during that entire period. As Clark Williams-Derry wrote for the Sightline Institute:

It would be funny — if the state weren’t planning billions in new highway investments in greater Seattle, based largely on the perceived “need” to accommodate all the new traffic that the models are predicting will show up, any day now.

It causes few sleepless nights among my colleagues that this approach bloats engineering projects and budgets, increasing the size of contracts, fees, and compensation. It also creates few incentives to question the value of traffic modeling deeply or seek alternatives to an approach that relies on projections of traffic known to be false.

Approaches that rely on traffic projections trade the insecurity of not knowing the future for the false confidence that comes from modeling. But if we want to build fiscal resilience in our communities, It is better to acknowledge the dynamic nature of traffic. Once we do that, we will stop overbuilding our transportation systems at terrible costs, and begin investing in systems that are adaptable, safe, and wealth-generating.