How 'border vacuums' prevent revitalization

Many of Jane Jacobs' ideas – particularly the need for cities to have mixed-use districts and “eyes on the street” – are well known by now. But the sheer density of ideas (no pun intended) in The Death and Life of Great American Cities is such that many of her poignant concepts are still overlooked. One such concept that I think deserves more attention, particularly in Baltimore, is the danger of creating what Jacobs called “border vacuums.”

The Highway to Nowhere is Baltimore's most notorious border vacuum

What is a border?

In Chapter 14 (“The Curse of Border Vacuums”) Jacobs defined a border as the perimeter of a large single-use territory or corridor (often a transportation corridor). Some common transportation borders are railroads, highways, and arterial roads. Some common territorial (institutional) borders are university and hospital campuses, office parks, housing projects, superblocks, strip malls, and sports and convention facilities.

How do borders create vacuums?

As Jacobs goes on to discuss, despite the usefulness of the transportation corridors and institutions in question, their peripheries pose some very real problems:

• Transportation corridors like railroads, highways, and arterial roads tend to form “Chinese walls” because there are limited opportunities for crossing them to get from one district to another. Even if there are passages underneath elevated sections or bridges over sunken sections, the crossings are often so unpleasant (or perceived to be dangerous) that they discourage casual crossing. Many corridors thus tend to disrupt the continuity of the urban fabric, and the resulting fragmented/isolated neighborhoods can lose their economic and social connections with the rest of the city.

• Large single-use institutional areas also tend to dampen our desire to cross them to get to another urban district: “Housing projects are examples of this. Project people cross [the border] back and forth [but] the adjoining people stay strictly over on their side of the border and treat the line as a dead end (261).”

• Some borders eventually behave like gangrene, gradually deadening the streets and blocks around them: “The root trouble with borders is that they are apt to form dead ends for most users of city streets. Consequently, the streets that [go to] a border are bound to be deadened places. They fail to get a by-the-way circulation of people going beyond them in the direction of the border because few are going to that Beyond. A kind of running-down process is set in motion (259).”

• A city may be able to overcome a few scattered borders (a parking lot, a vacant lot, a vacant building, a blank-walled building, or a 9-to-5 office tower here and there), but even these, if they aggregate into larger groups, can become formidable border vacuums: “Wherever a significant “dead place” appears on a downtown street, it causes a drop in the intensity of foot circulation there. Sometimes the drop is so serious economically that business declines to one side or the other of the dead place. The role of the dead place as a geographic obstacle has overcome its role as a contributor of users (263).”

The Inner Harbor narrowly avoided becoming another border vacuum.

However, some borders can become very desirable. The Inner Harbor had devolved into a border vacuum by the early 1970s, but by “activating the edge” with recreational attractions, the city turned the waterfront into a vibrant area. But it was actually the adjacent context of urban fabric that made this possible: Baltimore ultimately left the waterfront's adjoining commercial and residential districts intact rather than separating them with highways.

Had the highways been built – as was the case in so many other cities now trying to revive their isolated waterfront scraps – the waterfront border vacuum would likely have become worse because the city would not have been able to activate the edge with the fabrics of Federal Hill, Otterbein, Downtown, Fell's Point, and Canton.

I should point out – and Jacobs does this herself – that this is not an issue of “borders = bad and unnecessary.” That would be an extremely simplistic argument. After all, if institutional and transportation borders didn't fulfill a purpose, they wouldn't be there in the first place: “Many of them are most important to cities. A big city needs universities and large medical centers. A city needs railroads and expressways. The point is hardly to disdain such facilities or to minimize their value. Rather, the point is to recognize that they are mixed blessings. If we can counter their destructive effects, these facilities will themselves be better served (265).”

Likewise, when I discuss specific Baltimore transportation and institutional border vacuums below, my intention is not to criticize the institutions or transportation amenities themselves, but merely to acknowledge their (often unintentional) vacuum side effects and to explore strategies for fixing them.

How have border vacuums affected Baltimore?

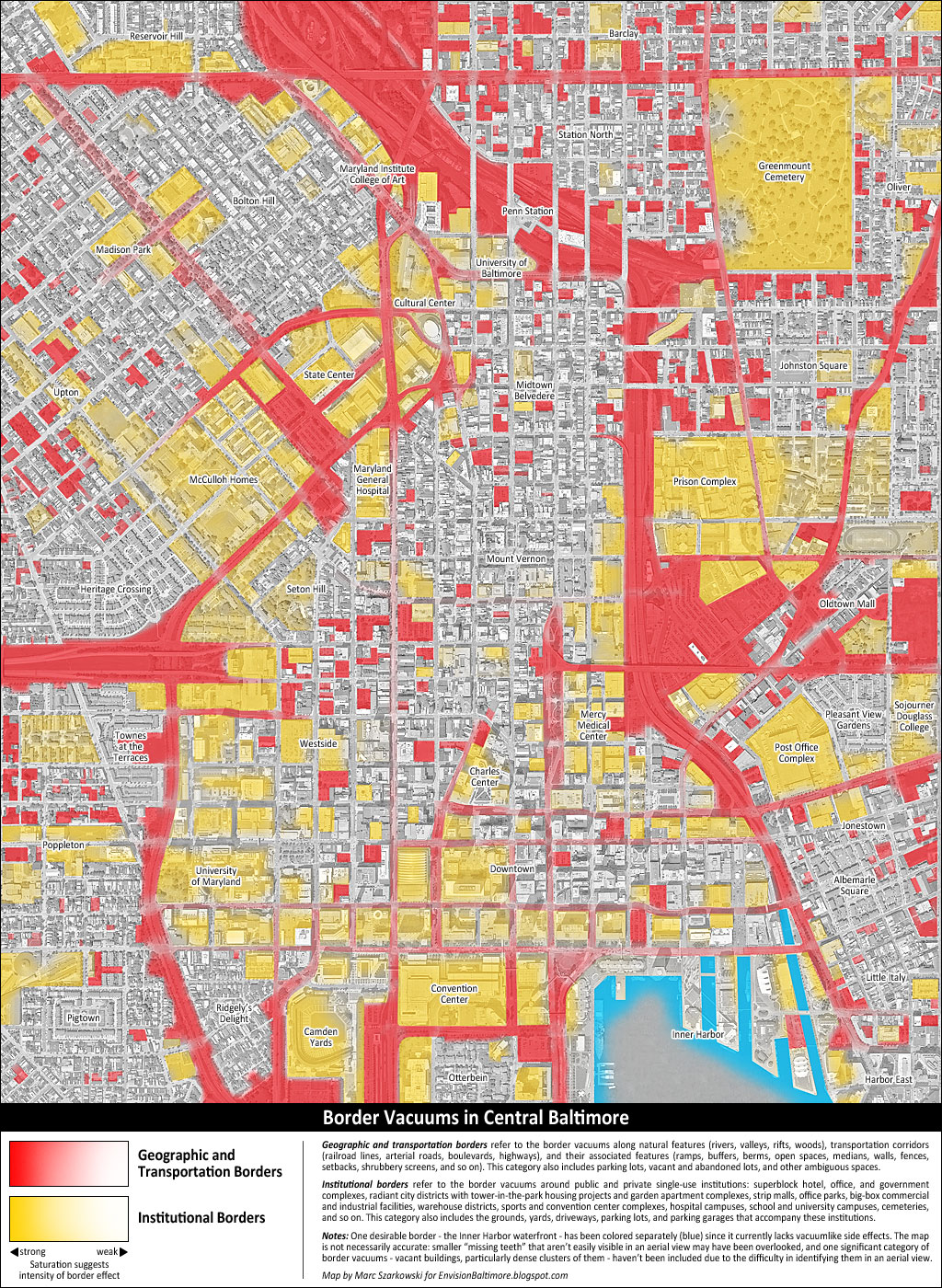

I created the map below to highlight central Baltimore's most commonly perceived border vacuums. Several are worth discussing in detail:

Border vacuums in Baltimore: Click for more detail

It's hard to extend the fabric of promising neighborhoods if they're hemmed in by so many border vacuums. For example, it's currently impossible for revitalization to spread north from Jonestown and Pleasant View Gardens across the combination of parking lots, the Post Office complex, the Oldtown Mall (whose tiny Stirling Street hamlet can't expand either), the prison complex, and the surrounding housing projects.

Revitalization can't spread east from Midtown across the JFX barrier to Johnston Square either, and even with five bridge connections across the JFX and the Northeast Corridor, the revitalization in Station North has been agonizingly sluggish and uneven (Station North also has the additional barriers of North Avenue and Greenmount Cemetery).

Also note how MLK Boulevard and its associated institutional vacuums (State Center and the McCulloh Homes in particular) prevent a stronger connection between Bolton Hill/Upton and Seton Hill/Mt. Vernon/Midtown. The MLK border vacuum continues south across the Highway to Nowhere (itself an infamous border vacuum) to separate Poppleton from downtown. There's been disappointingly little revitalization in West Baltimore despite the generous outpouring of funds over the years, and there probably will be no meaningful revitalization until the MLK border vacuum and its connecting/associated border vacuums are dissolved.

North Avenue was once a vibrant “seam.”

One particularly interesting border vacuum is the section of North Avenue between the JFX and Eutaw Place. In 1950 this stretch of North Avenue was narrower, it had more intersections with cross streets (and thus smaller blocks more appealing to pedestrians), and it was enclosed with mixed-use buildings. Although it was an important avenue and landmark, the North Avenue of 1950 was not a barrier. It was what Jacobs, citing Kevin Lynch, called a “seam”: “An edge may be more than a barrier if some motion penetration is allowed through it – if it is structured to some depth with the regions on either side. It then becomes a seam rather than a barrier, a line of exchange along which two areas are sewn together (267).”

That last phrase - “a line of exchange” - perfectly described this section of North Avenue in 1950. Although the neighborhoods to the north and south of this seam had their own distinct identities, the commercial thread that wove them together (stores with apartments above, movie theaters, and the streetcar line) made interaction easy and pleasant.

The same section of North Avenue has since devolved into a border vacuum.

What's this section of North Avenue like today? It has devolved into a border vacuum so harsh that it wouldn't be all that hyperbolic to describe it as the boundary between two different countries. Almost everything in the above photo is gone: the avenue was widened, the unifying central transit seam was pushed to the sides, the mixed-use “street wall” urban fabric was obliterated, several intersections and cross streets were removed, the resulting superblocks were filled with parking lots and Radiant City complexes (such as Madison Park North, the “Murder Mall”), and the periphery of the avenue was enclosed with fences, berms, and shrubbery buffers. It is now a literal wall between Bolton Hill and Reservoir Hill.

For some time now, people have wished that Reservoir Hill would match or even exceed Bolton Hill in splendor. It has grander rowhouses, after all, and it enjoys a proximity to splendid Druid Hill Park (interestingly enough, that connection was also frayed after WWII when Druid Park Lake Drive was built). Although there has been some faint revitalization in pockets of Reservoir Hill (and note: mostly along streets that still connect to Bolton Hill!), it too will probably not enjoy a comeback until the North Avenue border vacuum is dissolved.

Unfortunately, recent infill projects along the northern edge of Bolton Hill, rather than reconnecting to Reservoir Hill, have turned their backs on it instead. The MICA Gateway dormitory offers a blank wall to North Avenue, and the Spicer's Run development, while it did a good job reconnecting to Eutaw Place, made no effort to reconnect to North Avenue either. While the fear over connecting to a crime-ridden corridor is understandable (more on this below), I'd argue that the crime in the corridor won't be overcome unless there are reconnection attempts on both sides. Paradoxically, fences and buffers only exacerbate the problem.

Many border vacuums around Baltimore's stabler neighborhoods have been reinforced over the very understandable fear of crime. Some of these border reinforcement strategies are descendants of Oscar Newman's Defensible Space theory, and unfortunately some of his ideas conflict with the effort to create continuous urban fabrics. While I strongly support Newman's argument that “ownerless” public spaces, such as the grounds of Radiant City projects, can induce crime and disorder due to their inability to support natural surveillance (in this respect Newman's argument is identical to Jacobs'), I think some of his solutions (urban cul-de-sacs and self-contained mini-neighborhoods) may not be appropriate long-term strategies. A city of gated neighborhoods eventually stops functioning as a city, and the gate strategy doesn't really address the underlying roots of crime.

What happens when there are no border vacuums?

Contrast the neighborhoods we discussed above with the neighborhoods of south/southeast Baltimore: the lack of border vacuums has allowed revitalization to flow freely from Otterbein to Federal Hill and further south to Riverside and South Baltimore. Over the years revitalization has also swept freely from Fell's Point to Upper Fell's Point to Butcher's Hill, and it is now creeping into Washington Hill (perhaps revitalization would have crept in even earlier if it hadn't been forced to sidestep the Perkins Homes border vacuum) and Patterson Place. Revitalization has also flowed east to Canton and Brewer's Hill, and it's now pushing into Highlandtown, with stirrings of revitalization beginning to appear in Linwood. It eventually will spread to McElderry Park and Ellwood Park if the (comparatively minor) Pulaski Highway border vacuum is dissolved.

Revitalization has been able to spread freely across these neighborhoods – tying them together in the process – because there are no border vacuums on the scale of those that divide and surround the neighborhoods discussed earlier. If there had been the equivalent of a North Avenue or a MLK Boulevard dividing, say, Canton from Highlandtown, would revitalization have been able to spread as easily, or would it have halted in Canton? Encouraging continuity of the urban fabric is critically important if Baltimore wants to have a unified and vibrant center city district. Because this strategy has not always been acknowledged, the city has often (and unsurprisingly) resorted to the strategy of airlifting money into isolated areas, with very little to show for it.

In the next installment on border vacuums we'll look at strategies for dissolving them (from the cheap and simple to the complex and pricey), and we'll see if/how these strategies could apply to specific Baltimore border vacuums.

This piece originally appeared in the EnvisionBaltimore blog.

For more in-depth coverage:

• Subscribe to Better! Cities & Towns to read all of the articles (print+online) on implementation of greener, stronger, cities and towns.

• Get the January-February 2012 issue. Topics: Made for Walking, walking audits, Takin' it to the streets, Queens development weathers Sandy, Shared space taken to a new level, Streetscape spurs downtown turnaround, Florida streets manual gets traditional neighborhood chapter, Is better parking lot design enough?, Cities in small metros growing, Redesign arterial streets for pedestrians.

• Get New Urbanism: Best Practices Guide, packed with more than 800 informative photos, plans, tables, and other illustrations, this book is the best single guide to implementing better cities and towns.