Ambitious plan to replace tree canopy lost to storm

Cedar Rapids, Iowa, will plant 42,000 street and park trees and advise private landowners on how to replace a half million more to recover from a major August, 2020, derecho storm. The 10-year equitable tree recovery plan, ReLeaf Cedar Rapids, is a collaboration of the city, nonprofit Trees Forever, urban planner Speck & Associates, and landscape architects Confluence.

The plan focuses on when, where, how, and what species to replant to restore the canopy. “In addition to the actually very complex tasks of budgeting and distributing the trees over 10 years, the plan recognizes that the trees we choose and the places we put them, and even the order in which we plant them, can be done well or badly in a way that will have better or worse outcomes,” Jeff Speck told The Gazette newspaper.

About 34,000 trees will be planted on streets, and 8,000 in parks—38 of which were the subject of detailed landscape design. Plantings on public land will cost an estimated $37 million, and the city has pledged $1 million a year, every year, for the task. Trees Forever has raised an additional $1.5 million so far, and ReLeaf Cedar Rapids will tap other sources like federal grants to cover the rest.

About 85 percent of the city’s land is privately owned. A yard tree plan was created for homeowners, and an institutional tree plan for large land owners like colleges, private schools, golf courses, cemeteries, and religious campuses. But the chapters addressing streets and parks are considerably more directive.

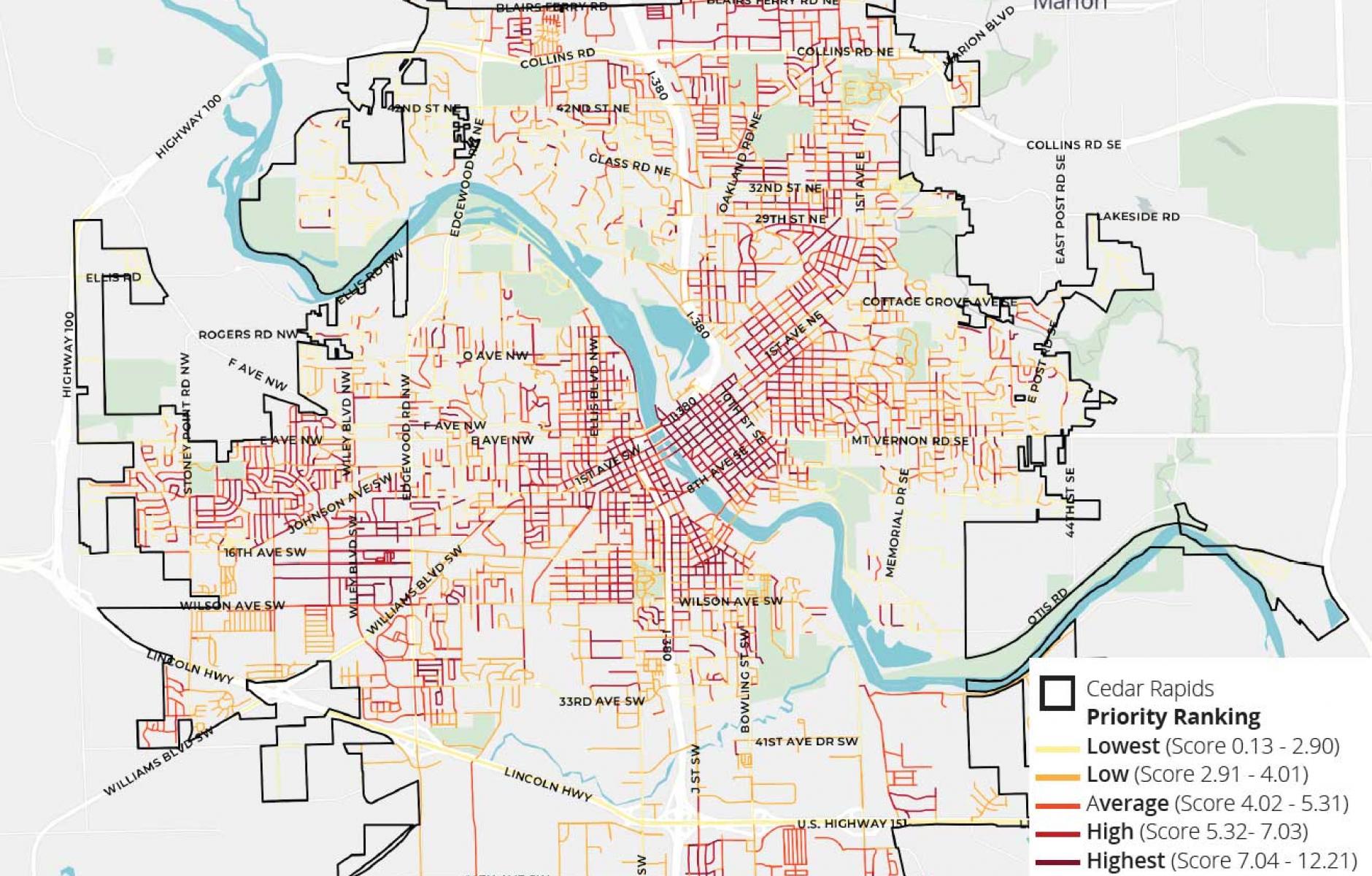

Priority for replanting street trees (see graphic at top) takes into account many factors, including type of street, tree loss due to the storm, pedestrian infrastructure demand, total number of vacant planting spots, and, importantly, “social equity score,” which is a measure by nonprofit American Forests that combines neighborhood canopy, income, race, and other factors.

ReLeaf Cedar Rapids calls for planting mostly trees that grow tall and wide—and also native species that support the food web and provide habitat. The tree list has three categories: Superior, which meet all of the desired characteristics; Allowed, which are big, locally adapted trees that don’t support the food web quite as well (but may be more available on short notice); and Contingent, which are smaller trees planted only where large trees won’t work, like under transmission wires. Despite the suitability of maples, none will be planted, because they are the most common species of what remains and are already overrepresented. A humorous subchapter in the plan is called “Enough with the Maples Already.”

The plan also works hard to advance the New Urban practice—contrary to some conventional urban forestry thinking—of planting consistent species in steady rows. “Plant material diversity is most effective when practiced city wide, and not street by street,” Speck told Public Square.

Cedar Rapids, a city of 137,000, lost at least half of its tree canopy in an event that Speck calls the largest urban-storm tree disaster in modern American history. He got the call to assist with the plan after working extensively with the City over the last decade on walkability, including converting one-way streets to two-way, replacing traffic signals with stop signs on low traffic volume intersections, and adding bicycle infrastructure.

The plan could be useful for urban tree planting efforts in other cities, not just Cedar Rapids, and Speck encourages planners to borrow directly from whatever sections may apply. He notes:

- It incorporates the very latest in best practices, attempting to correct some misunderstandings that have proliferated nationwide.

- It uses tremendous amounts of data and analysis to prioritize replanting according to a set of principles chosen through a public process, especially social equity and habitat preservation.

- It uses a magazine format, highly accessible graphics, and novelistic writing to reach the widest possible audience.

- It is extraordinarily ambitious in terms of not just replacing, but exceeding the tremendous amount of canopy lost.

- It has many features and much text that, while directed at the local circumstances, could easily be adapted into urban forestry plans nationwide.