What covid proved about traffic safety

In mid-April of 2020, we published an article indicating that as traffic was plummeting, traffic deaths were rising. This counterintuitive claim was not backed by firm numbers at the time, and the world was more focused on deaths from the pandemic anyway.

But as Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns reported in his book Confessions of a Recovering Engineer, this observation turned out to be entirely accurate. Vehicle miles traveled dropped substantially in the pandemic. By August of 2020, it was down 10 percent year over year, an unprecedented rate. Even in the Great Recession of 2008, VMT dropped only about 2 percent. Meanwhile, US traffic deaths rose 7 percent in 2020 and another 10 percent in 2021.

“The way that traffic engineers approach safety, safety is directly correlated with vehicle miles traveled,” says Marohn. “If fewer people are driving, fewer drivers will make errors, and that is the major cause of crashes and fatalities.”

The data was at first baffling to safety and transportation officials. After further research, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), part of US DOT, identified the cause as reckless driving. In an Open Letter to the Driving Public last year, NHTSA reported that speeds increased by 22 percent in select metro areas 2020, and they admonished drivers to slow down. The administration said that drivers “took more risks,” leading to the rise in fatalities.

Under stress of the pandemic, Americans became maniacs on the road, according to that theory. Convenient for traffic engineers and transportation planners, this theory places all of the blame on the public, and none on the professionals responsible for road design.

The conclusion also ignores years of research calling into question the fundamental approach, called “forgiving design,” for safe engineering of streets. Study after study shows that urban streets designed in a way that is less forgiving to drivers are safer. Marohn has a theory on the counterintuitive impact of covid on traffic safety that accounts for all of this.

The pandemic reduced congestion on roadways to such a degree that drivers were finally able to drive according to how these roadways were designed—at higher speeds, he says. At higher speeds on complex urban thoroughfares with other users like pedestrians and bicyclists, fatalities shot up, he explains.

“People have always engaged in risky behavior, but traffic congestion was no longer there to get in their way,” says Marohn.

Traffic engineers have spent a century designing roads that feel safe going faster than the speed limit. It’s not uncommon, Marohn says, to have a thoroughfare designed for 60 mph, with speeds of 40 mph, posted at 25 mph. If such a thoroughfare has many people living, shopping, and engaging in other activities along it, along with pedestrian activity, deaths and traumatic injuries are inevitable, he explains.

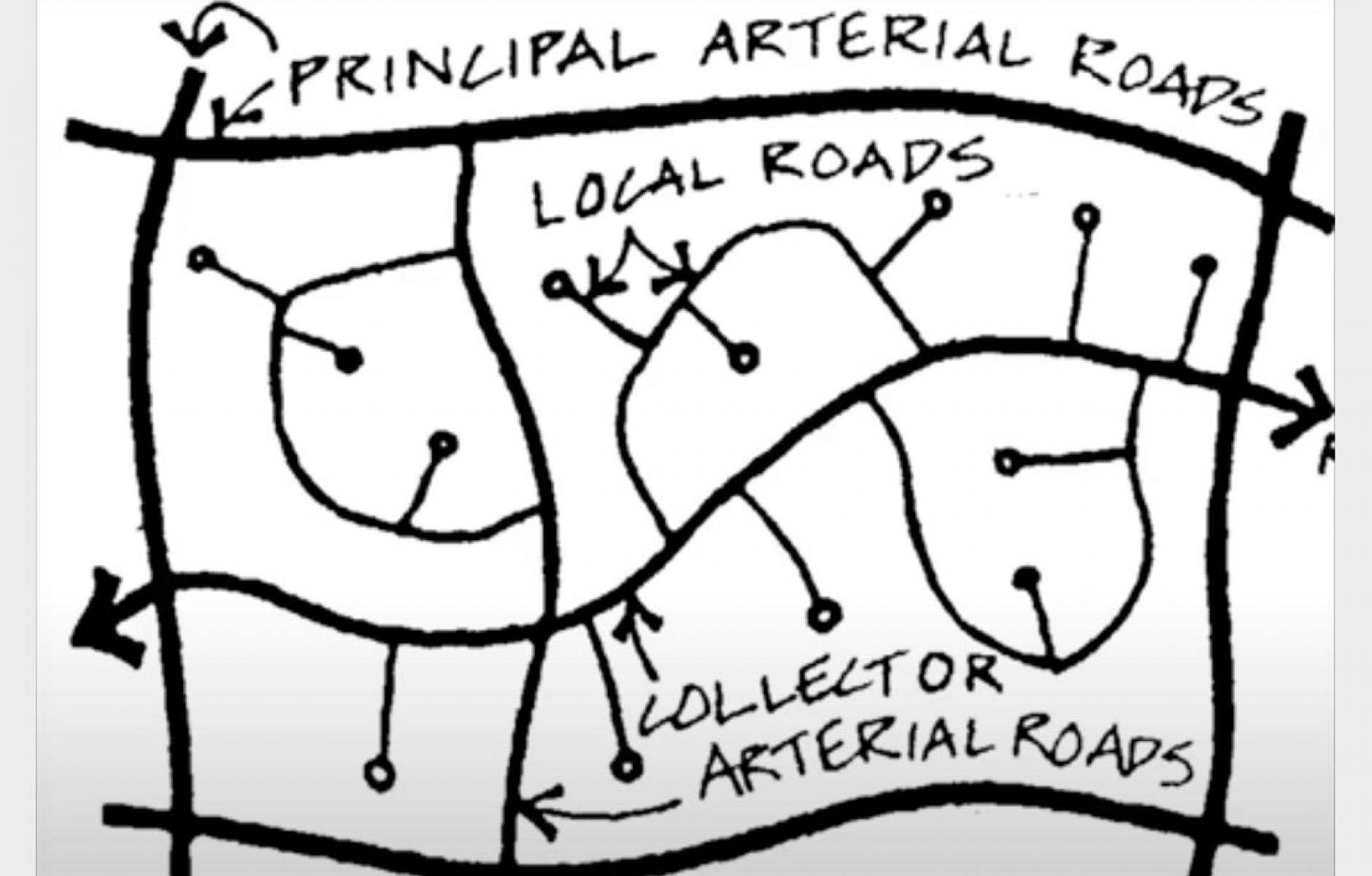

Outside of historic street grids, our thoroughfare system combines hierarchical networks, where smaller local roads funnel into big arterial roads, and forgiving design. “We increase safety by giving drivers more room.” That means making lanes wider and removing obstacles from the edge of the roadway. That leads to higher speeds, making urban streets less safe.

The hierarchical networks lead to congestion, in the same way that rivers flood when there is too much rain in the watershed. Congestion creates friction in the system that slows drivers down and, ironically, boosts safety. When the reverse happened in the pandemic, safety dropped.

Marohn’s theory makes far more sense than the dogmatic clinging to 20th Century design principles for thoroughfares. In urban areas, safety will only be improved by a network of streets that both disperses and calms traffic. These streets are safe not only when there is congestion, but also when there is not.