Ten ways to build small-scale urbanism

Daniel Burnham said “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized.”

Burnham made his career out of big plans, from the 1893 Chicago world’s fair, to the 1909 Plan of Chicago, to the design for the magnificent Union Station in Washington, DC. Such plans and projects are few and far between these days. By contrast, the movement toward little plans—small-scale urbanism—has been, well, very big in recent years.

Ever since the global recession of 2008, a growing number of urbanism practitioners and developers have been attracted to working incrementally, at the small scale. Building small has many advantages: It reduces capital and risk; It is quicker to get approved and implemented; the benefits are realized sooner; it is open to small operators; It is built with many hands, adding richness and the intelligence of multiple minds working independently; It is flexible over time. An abundance of mini-movements has emerged for making small improvements to cities and towns, most of them related in some way to New Urbanism. New Urbanism is a movement that works at a wide range of scales, from the design of small buildings to regional plans.

The New Urbanism philosophy adds richness to small-scale development, because it offers design principles to work toward—such as walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods or 15-minute cities. That way, the small developer or designer can benefit from the big-picture vision that Burnham alluded to, while only providing a small piece of the finished outcome. Building a neighborhood over time, with many hands, provides a richness of culture and ideas that cannot be achieved by a single designer.

Incremental Development

The incremental development movement grew out of the observation that great places are built in small increments. The sprawling of America grew hand in hand with the supersizing of the development industry. Incremental development offers a way for small developers to work together to build a complete neighborhood, employing the power of collective love of place.

The Incremental Development Alliance (IncDev) was founded in 2015 by urbanists active in CNU. “The Alliance part of our name celebrates the many individuals, institutions, foundations, and grassroots groups that are our allies in this work. We are an Alliance of doers dedicated to our neighborhoods across this continent,” the group says on its website.

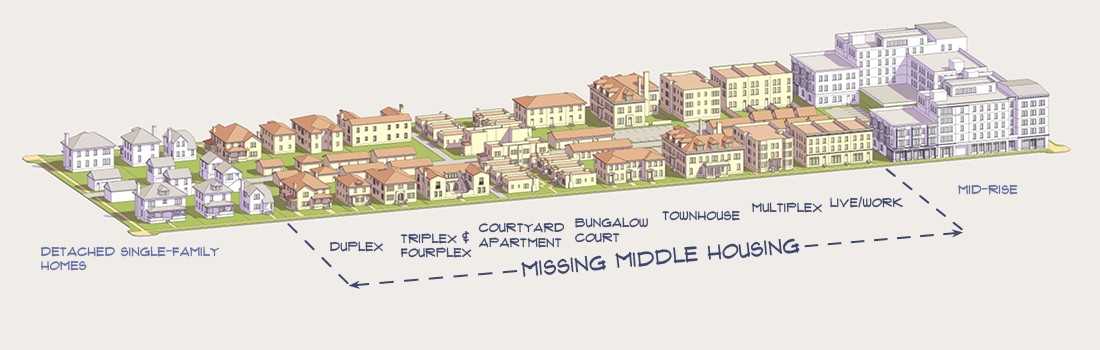

Missing Middle housing

Berkeley-based architect Dan Parolek coined the term “missing middle” about 10 years ago, accompanied with a diagram, to communicate the housing choices—increasingly in demand today—that are ignored or discouraged by conventional planning and development. These types range from small-lot single family and townhouses (with or without accessory units), to stacked townhouses and flats, duplexes, triplexes, quadriplexes, courtyard housing of various kinds, and small apartment buildings. Missing middle offers low-rise density and diversity, and forms the backbone of the quintessential American neighborhood. Over the past decade, the term and concept “missing middle” has become widespread in the land-use and real estate industry.

Lean Urbanism

Lean Urbanism is a multidisciplinary movement to lower the barriers to community-building, to make it easier to start businesses, and to provide more attainable housing and development. It focuses on systems, such as regulations, that form barriers to small-scale land-use and economic development.

Through the Project for Lean Urbanism, Lean seeks more efficient ways to achieve holistic communities to allow small operators to take part. Great neighborhoods need to be built by multiple hands—including those with limited capital to deal with red tape. One idea to come out of Lean is the “pink zone,” a play on the concept of lightening red tape. As the late, great urbanist Hank Dittmar put it, “It could be as big as a district or as small as a corridor, but it identifies a series of short-term projects that would catalyze development.”

Tactical Urbanism

Tactical Urbanism is a tool and set of practices for enlivening and improving public spaces with temporary or semi-permanent changes and structures that can be implemented quicker, with less money, to test out ideas for the public realm. Instead of planning just on paper, which may take years to be implemented, Tactical Urbanism seeks to create urbanism directly—examples include a plaza, a bicycle lane, parklets in street parking spaces, outdoor dining on former automobile pavement, and traffic calming measures. The term was coined by Mike Lydon and Tony Garcia. See top photo.

Pop-up commercial

Pop-up commercial has been a part of the New Urbanism since Seaside, when the first store in the 1980s was made of plywood and built like an outdoor market. Pop-up commercial could include a tent or a shack, and, broadening the concept a bit, a food cart or truck. Maybe it’s a farmer’s market that enlivens a public space, and allows small operators to establish themselves—eventually moving to a storefront.

Pocket neighborhoods

A Pocket Neighborhood is a variation on the cottage court popularized by the book Pocket Neighborhoods by architect Ross Chapin. They are clustered groups of houses or apartments around a shared open space, with up to 12 living spaces. According to the website, “It is pattern of housing that fosters a strong sense of community beyond among nearby neighbors, while preserving their need for privacy.”

Accessory Dwelling Units

ADUs are among the smallest scale of housing, often affordable, and have been used extensively in new urbanist developments for more than three decades. As the name implies, accessory units are subordinate to, and located on the same lot as, a primary dwelling—essentially doubling the unit density of the lot. ADUs are a traditional housing type that was regulated out of favor in the second half of the 20th Century. But now they are catching on in a big way—states like California and Oregon, and many cities, are making them widely legal to build anew.

Cottages and tiny houses

After Hurricane Katrina, a large new urbanist charrette on the Mississippi Gulf Coast generated the idea of the Katrina Cottage, a tiny house that was used in place of trailers in recovery efforts, especially in Mississippi but to a lesser extent Louisiana. The design won awards, then faded from the memory of FEMA. Nevertheless, the concept of tiny houses has become a “small” movement. There are now more than 250 tiny house communities across the US, according to this list.

Building on alleys and mews

The middle of the block is often neglected in urbanism, but there is tremendous potential for small-scale development here. Many US cities have tens or hundreds of miles of alleys, often neglected, with significant capacity for new development. Chicago alone has 1,900 miles of alleys. Mews streets, which are pedestrian streets in the middle of the block, offer still more opportunities for new development. Daybreak Mews in Utah, where relatively affordable homes (because of their size) are getting a per square foot premium, shows the advantages of mid-block development.

Cute townhouses

Little townhouses are a resilient housing type in old American cities like Philadelphia, Alexandria, and Baltimore. Developers are out of the habit of building this housing type, and it doesn’t work well with a garage. On the plus side, small developer John Anderson notes that he has learned not to underestimate the power of cute houses. These townhouses are definitely cute, and they appeal to a strong market of small households today that want walkable neighborhoods. Petite townhouses are making a comeback in some places.