Slouching towards Cincinnati

Note: This article first appeared in Strong Towns.

A few months ago, I wrote a piece questioning the utility of the Brent Spence Corridor Project, a $3 billion highway widening project that includes the construction of a new companion bridge next to the Brent Spence Bridge, which crosses the Ohio River between Cincinnati and the Northern Kentucky city of Covington.

In recent months, it has become increasingly clear, if there was ever any doubt, that local and regional politicians—from the Cincinnati City Council and mayor all the way up to the governors and senators on both side of the Ohio River—plan to proceed full steam ahead. That rough beast that is the Brent Spence Corridor Project, its hour come round at last, is slouching towards Cincinnati to be born.

In an attempt to mitigate the damage from the current plan to simply Build Back Bigger, a group of local activists, architects, and urban planners calling themselves “Bridge Forward” have proposed a plan to redesign the project, with the goal of recapturing approximately 30 acres of land for redevelopment on the West Side of Cincinnati.

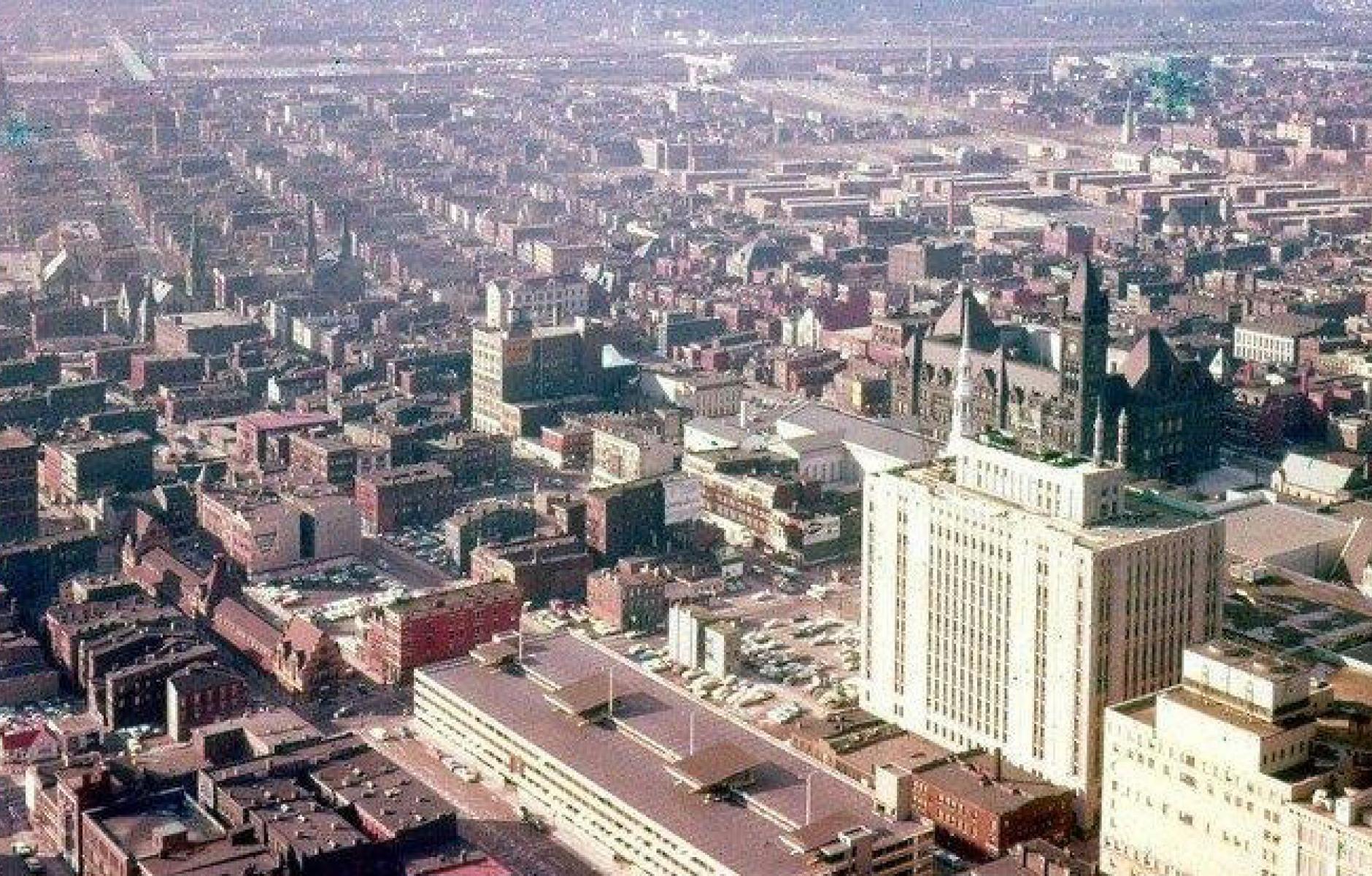

The West Side of Cincinnati could be considered a poster child for the devastation wrought by the highway builders of the past century. In an all-too-familiar story, the predominantly African-American population in the Kenyon Barr neighborhood of the city’s West End was displaced, the properties razed, and a shiny new interstate highway was slammed through a now mostly empty area that was renamed Queensgate.

From the perspective of Strong Towns readers, especially those familiar with the work of Joe Minicozzi and Urban3, the massive destruction of real estate and land value is obvious. The real shame is that the current design for the Brent Spence Corridor Project takes no account of the potential value that could be realized from reclaiming some of this land, and Cincinnati leaders up to this point have been seemingly ignorant of this potential, as well. This should be especially humbling for local leaders on the Cincinnati side of the river, since all of this land lies within Cincinnati city limits. To add insult to this ongoing land use injury, can you imagine inviting the Congress for the New Urbanism to Cincinnati in 2024, only to display our beautiful new highway expansion to the premier gathering of urbanists in the United States?

The current corridor plan highlights flaws in the way these projects are designed, which is something that Chuck Marohn routinely calls out in his talks on these topics. The nearly two-decade-old planning document for the Corridor Project has four chief aims:

- Improve traffic flow and level of service.

- Improve safety (for automobile users).

- Correct geometric deficiencies.

- Maintain links in key transportation and national defense corridors.

Noticeably absent from these objectives is any consideration given to the land use impact or the downstream social and environmental effects of the project. From the Cincinnati perspective, a corollary to the observation about land value destruction is the irreparable harm done to any attempt to make Cincinnati’s current development pattern financially sustainable over the long term.

The alternative proposal from Bridge Forward is pictured below. Working in concert with the local architecture and urban design firm GBBN, the Bridge Forward team has created a design which reclaims approximately thirty acres of land for redevelopment.

Even from the standpoint of someone such as myself, a concerned Cincinnati citizen who questions the utility of building a new bridge altogether, it is clear that the Bridge Forward proposal, if technically feasible, is preferable to the status quo design, which only serves to entrench a destructive status quo for another 50–100 years.

There is so much in the current design for the Brent Spence Corridor Project that highlights what is wrong with the Suburban Experiment—from the automobile-centric design perspective; to the lack of consideration given to the land use impacts of transportation infrastructure; to local and national politicians who are either ignorant of the financial recklessness at the heart of this development paradigm, or who go along with it to avoid stepping on the toes of the Infrastructure Cult. Thankfully, there still appears to be a window in which some major improvements to this project can be explored. One hopes that, if implemented, the improvements from the Bridge Forward design, or some subsequent adaptation, could be used in the future as an example for other similar projects elsewhere in the country (if they must be built at all).

If you’re a Cincinnati or Northern Kentucky resident interested in these sorts of issues, please consider going to www.bridge-forward.org, and click on the link to email local leaders to urge them to consider the Bridge Forward Proposal.