Why malls are a bad public investment

Note: This article first appeared on Strong Towns. Public Square editor Robert Steuteville is on leave through the last week of October.

Big investments can bring about big problems. Take the shopping mall, for instance: Built on the appealing premise of housing a bunch of commercial businesses under one, climate-controlled room with convenient parking just steps away from the entrance, these massive investments of money and space typically hinge on a few “anchor stores” (your Macy’s or Nordstrom’s) to pay the rent. If any of those depart, they leave a big empty space and a big financial problem for the mall owners (not to mention the city that should be collecting property taxes on the space). The mall starts lagging on upkeep and daily maintenance, the space becomes less appealing to visitors and before long, other businesses are leaving, customers are dwindling… It’s a downward spiral. What was once a promising venture is now a massive drag on its surroundings, losing the tax revenue it would’ve provided to the city, becoming a vast, wasted space, and even encouraging crime.

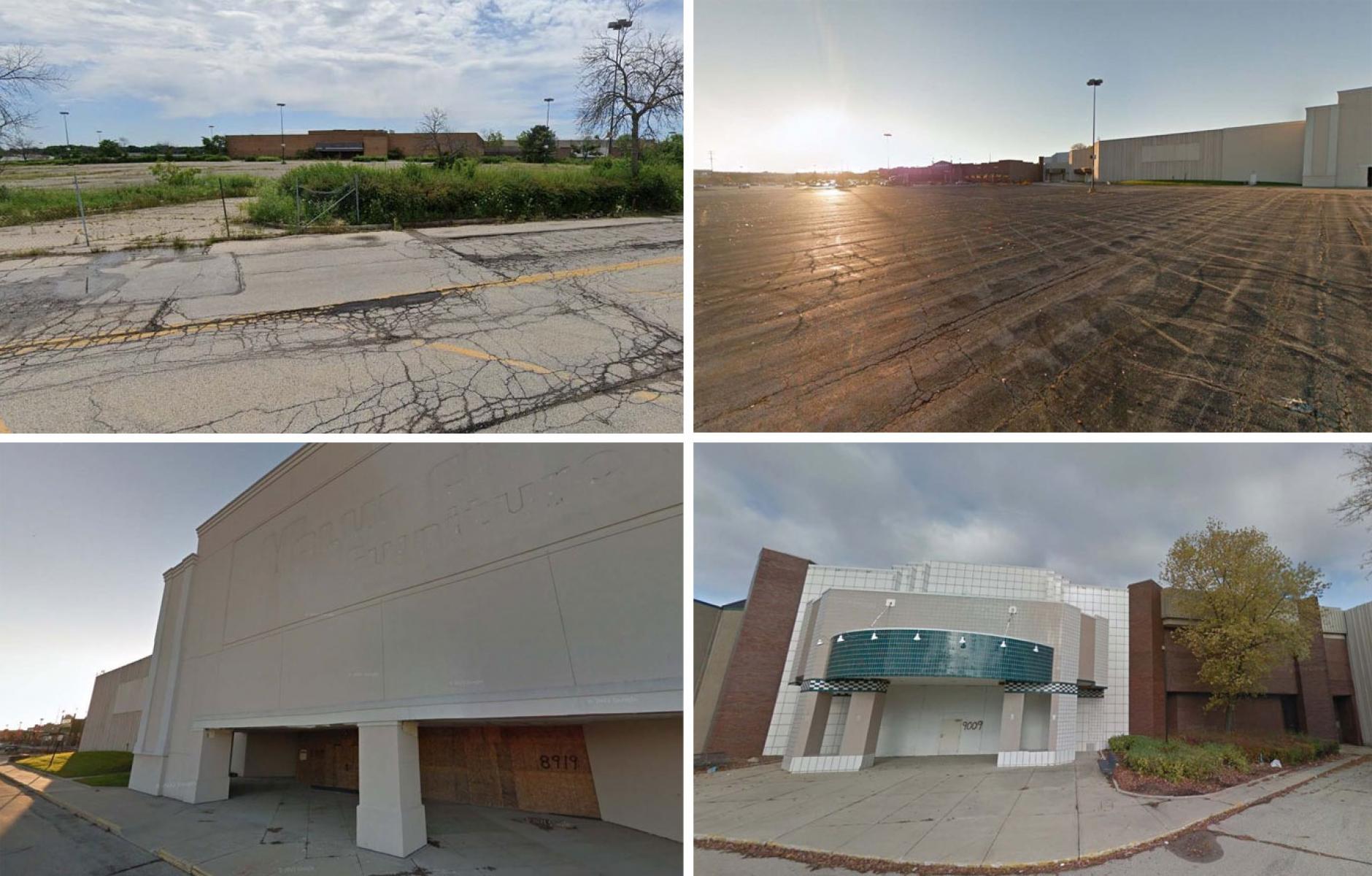

This familiar story took place at a mall in my city of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, called Northridge Shopping Center. The mall is located in a lower-income, edge area of the city. I’m sure when it was built in 1972, the mall’s developers painted a rosy picture that it would help economically lift up the area. Instead, today, the mall is making this neighborhood much worse. It closed in 2003 and a full 20 years later, it’s still vacant, an eyesore and an increasingly dangerous problem for the neighborhood and the city.

This year alone, according to an article from my local media outlet Urban Milwaukee, “police have been dispatched to the property 25 times … for reports of trespassing, vandalism or other property crimes.” Multiple fires—four in the last month alone—have demanded the time and energy of the local fire department and a maintenance worker was even killed on the premises a few years ago by “a high voltage transformer … previously damaged by scrappers.”

This is due, in large part, to the fact that a Chinese company purchased the mall 15 years ago and has been essentially holding it hostage ever since—making the bare minimum of payments to ensure it stays in their possession yet totally neglecting it and doing nothing to transform it into the “marketplace” the company originally proposed. The company is also failing to pay the (minimal) property taxes on the mall, depriving my city of needed revenue while also actively costing it money in the form of emergency personnel and resources dispatched to respond to the recent fires and vandalism.

The City of Milwaukee has made attempts to take control and demolish the building for the last several years, to no avail. This foreign company has refused to even respond to requests for more security and fencing at the property. It’s a nightmare, and an example of what happens when we go all-in on a big investment: we take on a big risk.

Public subsidies are propping up your mall

Interestingly, the Wikipedia entry about Northridge Mall claims that part of the reason it failed was that a promised freeway was never fully run out to the building (thanks to protests against that new road). In other words: one massive infrastructure project failed because another massive infrastructure project didn’t prop it up. Why on earth are we structuring our communities in this manner?

Also of note is a comment from the Urban Milwaukee article: “The mall’s competitors, including Mayfair, Brookfield Square, Southridge and Bayshore, have all received substantial public subsidies to help finance updates in the years since Northridge closed.” So even the malls that still survive today are able to do so because they’re propped up by public dollars.

I have been to a few of these malls in recent months. Bayshore is notable because it’s billed as one of the more upscale shopping centers in the region and structured as an outdoor mall rather than an enclosed space—two things setting it apart from places like Northridge. Or not... It used to be home to trendy shops and even some fancy restaurants (my husband previously bartended at one that served an expensive weekend brunch which included lobster). A recent trip to Bayshore showed half the storefronts empty, the existing ones filled with discount shops and temporary tenants. No doubt this is partly the result of the pandemic and an increase in online shopping. But if even the upscale mall is failing, that should tell us something about the viability of this model as a whole.

Because of the size of a mall, anything that would improve the space or give it a new lease on life must also come at a large scale. For one thing, it’s hard to find a quick new use for a space that is 80% empty parking lots. And it puts us in this spiral where only another huge company can fill the void. In the case of Northridge, at one point a large spice company was poised to buy the mall and use it as a factory or warehouse, but that fell through. So today, we have this foreign holding company that was probably the only buyer willing to put up the cash to purchase the place 15 years ago. And we’re stuck.

The mall model may have had its moment, but that moment is long past.

Doing a little math

When looking at the value of a development, it’s important to talk with hard numbers.

It probably won’t surprise you to know that the current tax value per acre of the mall property is a measly $44,752 (according to my back-of-the-envelope calculations). It occupies a whopping 46.5 acres of land, so that’s a whole lot of wasted, low-performing space that is, as mentioned above, actively costing the city money in emergency services, not to mention the large amount of roads, pipes, and electric lines that surround the mall. Assessment records that I could access go back to 2009, when Northridge was at its highest assessed value. Even then, it was only worth $75,270 per acre.

Now, this facility is on the very edge of the city, built in a very suburban, car-oriented style of development, so it would be unfair to compare its value to the value of downtown properties. Thus, I picked out a few single-story, suburban-style businesses nearby for a more reasonable comparison.

A Rocky Rococo Pizza (a Midwest chain of pizza restaurants) down the road from Northridge is worth $418,800 on the tax rolls and takes up 1.2 acres of land, giving it a value per acre of $349,000 (i.e., almost 8 times as valuable as the mall).

A Salvation Army Store down the block does far better, despite the fact that it looks to be permanently shuttered. That building takes up 1.6 acres of land and is valued at $1.4 million, for a tax value per acre of $860,187—19 times the value of the Northridge Mall.

Finally, just to stretch our comparison a bit further, I also looked at a small indoor food market in a different area of town, one which is built in a more traditional historic style of development but in a neighborhood that also has its fair share of crime, vacant buildings, and poverty. The Sherman Phoenix Marketplace has a lot size of almost exactly an acre and is currently assessed at $2,547,100—a whopping 57 times more valuable per acre than that old mall.

Looking at the “tax value per acre” shows us how much these properties are worth and how much they are paying in taxes, compared to the amount of land they take up. If a mediocre pizza chain and a thrift store are worth hundreds of thousands more than this mall, that should really tell us something about how wasteful the whole endeavor has been.

A different model for retail—one that has stood the test of time

So what would a commercial model look like that didn’t rely on huge upfront investments of land and buildings, that didn’t need millions in government subsidies to survive and fail to pay much back in taxes, that wasn’t dependent on a couple of large department stores to prop up the whole scheme—that wasn’t, in short, financially fragile?

Well, it would look like the main streets and downtowns that have been the standard way of building in cities for centuries: a street lined with small businesses, perhaps with apartments above the storefronts, where people can walk from shop to shop. When any one of those businesses leave, there is a vacancy that could be filled by something else. It doesn’t ruin the whole street. It’s not a mall reliant on a few anchor tenants or a single, absentee landlord to care for it. The buildings are owned by people who live in the city, maybe even the same people who run the shops or occupy the apartments above them.

In addition to the more modest turnover and tax productivity that a typical commercial street provides, it also offers more natural oversight from the people who live, work, and visit there—more “eyes on the street,” to quote Jane Jacobs. The abandoned Northridge Shopping Center has become a problem particularly because it is an enclosed space. People looking to get into trouble only need to get through the meager fencing around the property, then they’re free to sell drugs, start fires, or whatever else they’d like inside the walls of the mall. No one passing by will ever see.

I’m saddened for the people who live near Northridge and have to look out on it every day, probably experiencing more break-ins and crime at their own homes as the mall attracts people who are up to no good.

At the end of the day, huge projects can bring about huge problems and require huge amounts of time to solve them. Twenty years later, we’re still trying to solve this one. Every city should think carefully before allowing or investing in something on as big a scale as this mall, knowing the tremendous risk that comes with it. We’d do far better to take a fraction of the money we might have spent on mall subsidies and use it to spruce up our main streets; give start-up grants or loans to small businesses; and generally nudge our existing, valuable commercial areas to be a little stronger.