How physical activity, land use, transportation, and zoning intersect

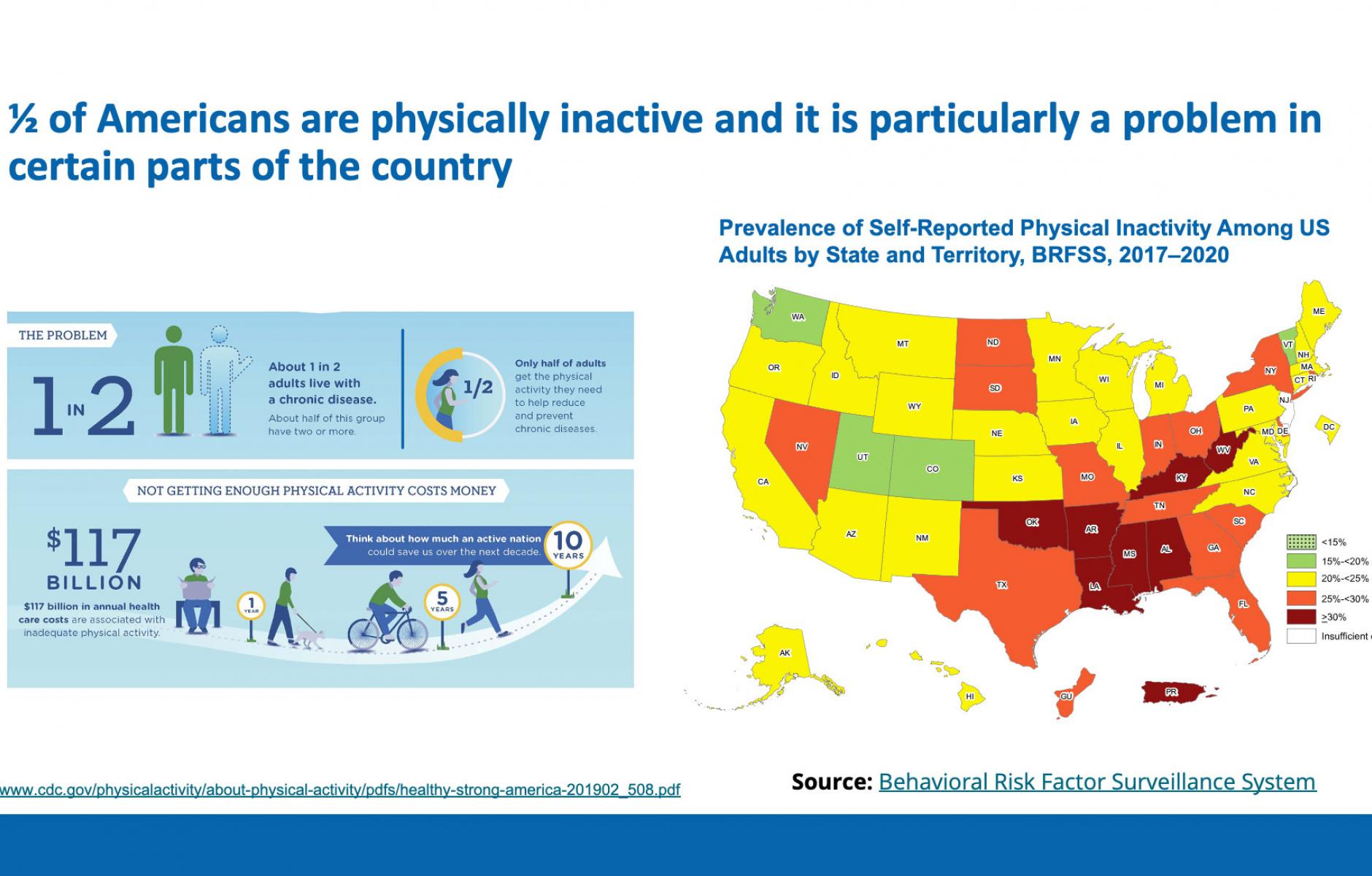

In an On the Park Bench webinar, Jamie Chriqui, PhD, reports on the intersection of physical activity, land use and transportation, and zoning. This matters because half of the US population is physically inactive (more prevalent in the Sunbelt), and inactive people are far more likely to have chronic disease, including severe covid. The estimated cost of inactivity is $117 billion annually, she tells the audience. Chriqui is Associate Dean and Professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois Chicago.

There are two major categories of what communities can do to promote physical activity, she says.

One, pedestrian, bicycle, and transit transportation systems:

- Street pattern design and connectivity

- Pedestrian infrastructure

- Bicycle infrastructure

- Public transit infrastructure and access

Two, land use and environmental design:

- Mixed land use

- Increased residential density

- Community or neighborhood proximity

- Parks and recreational facility access

A combination of these two approaches has been shown to increase physical activity, she said. Watch her presentation and the discussion with CNU's Marsha Garcia and the audience:

The goals can be accomplished through new urbanist code reform zoning, or through traditional Euclidean zoning. However, goals are facilitated through code reform—including form-based, traditional neighborhood development, and Transect-based codes, the SmartCode, transit-oriented development zoning, and similar regulation. Activity-oriented built environment features are addressed more frequently in jurisdictions that have reformed their zoning, she says.

Chriqui reported on research from PAPREN, the Physical Activity Policy Research and Evaluation Network, which examined the zoning codes of 2,300 municipalities nationwide, representing 55 percent of the population, in a huge effort. Each code was individually examined for markers of policies that encourage physical activity. (Chriqui said she has employed a small army of planners and students over the years to look at codes). PAPREN is funded by CDC, and the network is open to practitioners (or anybody) who wants to join.

Code reform connected to New Urbanism and related trends increased 53 percent—up to 26 percent, from 17 percent—in all municipalities studied.

In the last decade, her research found that more municipalities are calling for features in the built environment that promote physical activity. However, the prevalence is much higher in code reform municipalities—often double, or nearly double. The features include reduced parking, pedestrian plazas, public transit access, pedestrian amenities, bicycle amenities, streetscape improvements, and open/greenspace. Often, codes provide density bonuses for developers who provide the physical activity supportive infrastructure. That’s a double benefit, because density itself may provide for greater physical activity.

The code reform hotspots in 2010 were Florida and California, but other hot spots emerged in 2020, such as the mid-Atlantic region. (Municipalities near other communities with form-based codes often go on to adopt form-based codes themselves. They seem to like what they see.)

Code reform creates places where people want to live, work, and play, Chriqui says. Investing in that infrastructure helps to boost physical activity, along with co-benefits like property value increases, neighborhood revitalization, and other health and social improvements.

Chriqui’s research has connected code reform zoning with more physical activity, reduced rates of cancer, and higher rates of people walking and biking to work.