When is density good, and when is it harmful to cities?

Seventy-one New Urbanists, including many of the movement’s leading lights, gathered in Washington recently to address a set of increasingly urgent questions: If density is good for a city, how much of it should there be? How tall should the buildings rise? What forms should they take?

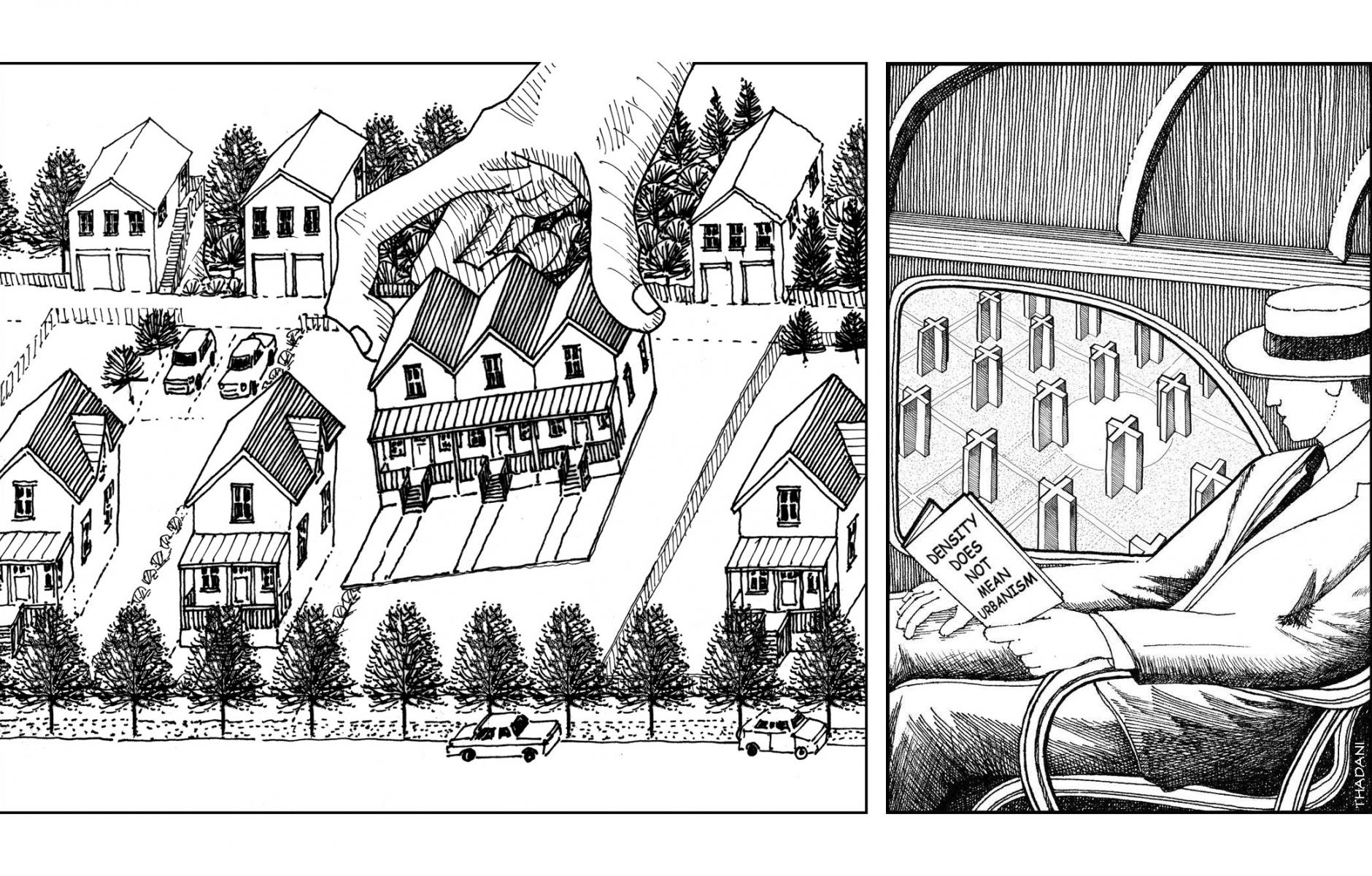

Everyone attending the March 31-April 2 event hosted by CNU’s District of Columbia chapter seemed to agree that not all density is good. Architect and chapter president Dhiru Thadani opened the Council—on “Density Without Urbanism/Urbanism Without Density”—by showing rows of high-rise apartment buildings stretching seemingly endlessly across China. “People are just being warehoused in large buildings,” he reflected.

While China propels vast assemblages of towers into its skylines, North America is experiencing a lower yet also disquieting form of densification: mid-rise buildings sometimes pejoratively called “stumpies.” The typical “stumpy” (the term seems to have originated in the press) consists of five stories of wood-framed apartments sitting atop a concrete podium often containing commercial space or enclosed parking at street level.1

Stumpies can fill entire city blocks. Generally, the buildings lack architectural distinction. The exterior is frequently divided into many vertical segments, sometimes in contrasting materials or colors, in an attempt to make whole thing look less bulky and overwhelming. This fragmented esthetic dismays many city-lovers. In January The New York Times published an article titled “America the Bland,” which reported, “Across the country, new developments are starting to look the same, raising fears that cities are losing their unique charm.”2

The Council discussed conflicts over urbanism and density, in hopes of encouraging density’s benefits and at the same time upholding New Urbanist aims such as walkability, diversity, and visual delight. Boston architect and urban designer Michael Dennis spoke for many participants when he said, “Some tall buildings are necessary for density. Tall buildings are not necessarily bad—though most are.”

When done well, density has much to offer. By bringing large numbers of people together, it can make public transit possible. It can help shops, restaurants, and other enterprises thrive. It can entice people to walk rather than drive to many everyday destinations. If dense development includes moderately priced or inexpensive housing, it can offset some of America’s mounting economic inequality. It also can reduce stress on the natural environment, by using resources more efficiently and emitting fewer greenhouse gases than sprawl does.

But density, when it’s badly arranged, when it clusters only the narrowest range of income groups, household types, and economic activities, can be stultifying. Rather than giving residents multiple options, it constricts their daily experiences.

The urbanism envisioned in the Council offers pedestrian-friendly streets, convivial public spaces, opportunities for neighborliness, and other virtues. “Density is made humane by urbanism,” said CNU President Mallory Baches.

Baches drew attention to the density of a number of New Urbanist developments, including these:

- Del Mar Station in Pasadena, California, with 347 units on 3.4 acres, achieves a density of 102 dwelling units per acre.

- Paseo Verde in North Philadelphia, with 120 units on 1.9 acres, 63.2 units per acre.

- Storrs Center in Connecticut, with 668 units on 47.7 acres, has 14 units per acre.

- Orenco Station in Hillsboro, Oregon, with 2,394 units on 150 acres, has 16 units per acre.

A development such as Orenco Station, near a light-rail line west of Portland, may not be dense by world standards, but it’s significantly more compact than many American suburbs. Its mix of uses, in a comfortably walkable setting, allows residents to get to cafes, shops, offices, and park land quickly, with less driving than the suburban norm. Orenco Station and Storrs Center are neighborhood-scale developments, and therefore density is a “gross” figure that includes streets and larger open spaces. On specific parcels near the transit station, Orenco’s net density exceeds 100 units per acre, according to planner Michael Mehaffy.

Six decades ago, Jane Jacobs suggested—based on lively mixed-use districts she had studied across the US—that the ideal big-city density is somewhere between 100 and 200 net dwellings per acre. By her calculations, the North Beach-Telegraph Hill section of San Francisco achieved a net residential density of 80 to 140 units an acre. Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square area contained 80 to 100 units an acre. Brooklyn Heights had 125 to 174 units an acre in its core and 75 to 124 in the rest. The most fashionable pocket of Greenwich Village boasted 124-174 units per acre, and the remainder of the Village ranged from 175 to 254 units an acre.3

In Jacobs’s view, “dense concentrations of people are one of the necessary conditions for flourishing city diversity.” But when density is excessive, an area often loses its variety; there ceases to be a healthy range of apartment size, household size, prices, income levels, and other characteristics. Successful neighborhoods, Jacobs argued, need buildings of differing ages, heights, inhabitants, and other attributes. Today’s stumpies typically lack such variety.

“New Urbanists don’t loathe stumpies enough—for the right reason, and creatively,” San Francisco architect Dan Solomon told the Washington gathering. He showed photos of a stumpy named Aqua, in Del Mar, California, that covers nearly all its land with four stories of apartments on top of a base of enclosed parking.

“The only public space is a gas station” on one corner of the site, Solomon pointed out. “The real entrance [to the housing] is the parking garage.” From the garage, residents walk to an elevator, then to a corridor offering no view out, and finally to the individual apartment. “That is the experience of life in the town,” he said. “It’s a horrible way of life.”

“Housers have come to believe in density,” Solomon said. Developers often fill their zoning envelope to the maximum, producing results that are boxy and monotonous. In Solomon’s view, there’s a need for a more flexible mode of development, one that lets architects employ more variegated forms and create more appealing streetscapes. He referred to this as “loose-fit” development, and said it’s far superior to today’s density-fixated straitjacket.

An example of Solomon’s design approach is Sansome and Broadway Family Housing: 83 affordable apartments occupying a 50-by-400-foot San Francisco piece of land that had previously been a ramp of the Embarcadero Freeway ramp. (The freeway collapsed in a 1989 earthquake.) The apartment project is articulated as two different forms: a six-story horizontal section that nods to historic brick warehouses nearby, and an eight-story, vertically-proportioned segment that relates to narrow buildings on the 25-foot-lots of North Beach and Telegraph Hill.

By breaking the building into two visually distinct segments, each connecting in its own way to San Francisco’s history, Solomon reaffirmed the city’s character—something that dense mid-rise projects often neglect to do.

John Torti of the Washington architecture firm Torti Gallas + Partners cautioned that the construction technology relied upon by “stumpies” is not necessarily the enemy. “Wood on a podium is not a dirty word,” he said. “It all depends on how you deal with the first floor.” What’s essential, in his view, is that the people putting up the building “revere the city”; a project has to have urbanism as its starting point.

Life in low-skyline cities

Scott Bernstein, cofounder of the Center for Neighborhood Technology, looked at density from the perspective of the eight-square-mile city where he lives: Evanston, Illinois, the 78,000-population home of Northwestern University, north of Chicago. Of Evanston’s 14,000 buildings, 98.6 percent are 1 to 4 stories high. The other 1.4 percent—194 buildings—are between 5 and 28 stories.

In other words, the preponderance of Evanston is close to the ground, a situation that most people in Evanston and across the US prefer. Yet the city’s neighborhoods are dense enough to offer plenty of destinations that are reachable on foot. Bernstein counted 234 businesses within a 15-minute walk of his home.

Compactness is an economic and ecological boon, he said, noting that vehicle miles traveled decline by 179 miles per household per year for every 1 percent increase in neighborhood compactness. With compact neighborhoods, people don’t have to own so many cars, he said. “We should be aiming for complete communities.”

CNU co-founder Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk was unable to attend the Council, but sent a short video in which she stressed the importance of choosing “building types that relate to the street.” Said Plater-Zyberk: “High densities can be achieved at low heights.”

The word “density” was itself the subject of considerable discussion in the Council. Some lamented that “density” doesn’t capture, in a positive way, what New Urbanists are aiming for. Some said “neighborhood compactness” is a better term.

How much building can existing cities accommodate? “Plenty,” said Torti. Mark Nickita of Detroit-based Archive Design Studio said the Motor City has an abundance of space. Detroit, its population having plummeted to about 650,000 from its 1950 peak of 1,850,000, is redensifying by building on its existing stock, adding public space, and creating mixed-use development and low- and mid-rise structures, Nickita said.

Detroit Is not alone. “Cities such as Lexington, Kentucky, could add 500,000 people without demolition,” said Thadani. “By building on underutilized sites such as vacant parking lots and abandoned buildings, it is possible to add 25 million people in existing cities. We could get a fair amount of density, which would increase the tax base.”

Neal Payton, head of Torti Gallas’s Los Angeles office, said California has begun to reap the benefits of the state’s recent housing production laws that aim at relieving the state’s chronic shortage of affordable dwellings. “Every municipality must allow auxiliary dwelling units (ADUs),” Payton noted. In three years, 63,500 ADUs have been built. No lot coverage restriction or minimum lot size stands in the way of ADU construction. In addition, impact fees have been reduced or eliminated.

Influenced by parking guru Donald Shoup, the state’s Assembly Bill 2097 has reformed parking requirements. The legislation eliminated minimum parking requirements for residential, commercial, or other development projects within a half-mile of a high-quality transit corridor or transit stop. Another law, Senate Bill 330, stipulates that no rezoning is needed if the proposed housing is consistent with the General Plan (comprehensive plan) and the municipality’s Objective Design Standards.

Assembly Bill 2011 provides a density bonus of up to an 80 percent if a development provides affordable housing. The size of the bonus depends on the units’ degree of affordability. Solomon, however, expressed reservations about some of California’s initiatives. He suggested that the state, in its zeal to obtain more housing, is pitting housing advocates against “people who love their California towns” and want to preserve them.

Payton lauded the state for allowing commercially zoned corridors to get residential construction, by right. This policy change stems from the work of regional thinker Peter Calthorpe, he said.

On the East Coast, Philadelphia offers “extraordinary lessons in building density at a rowhouse scale,” said Matt Bell, an architecture professor at the University of Maryland and a principal at Perkins Eastman. Bell said Baltimore was “built as a monoculture of rowhouses” and to a large extent remains so, but Philadelphia has more varied pattern. Though Philadelphia began with William Penn’s grid—which featured blocks as large as 400 by 625 feet—over the centuries many of those blocks have been subdivided in clever, adaptable ways.

The result, in some parts of Philadelphia, is streets of differing sizes, housing of varying types and dimensions, and a healthy intermixing of shops, restaurants, little parks, and other uses. Bell seemed to be talking mainly about Center City, but lessons from Philly’s core could be applied elsewhere.

“Urbanism cannot be made of object-buildings,” Michael Dennis emphasized. In his view, there are two conditions that generate urbanism: First, buildings should align on the street or square, and should be close enough to define space. Second, there must be walkable neighborhoods, serving a mix of functions.

The continuing issue of height

Dorian Moore, a partner at Archive Design Studio, related that in Toronto, “The tower is seen as the rebound agent from the pandemic.” The emphasis in Canada’s largest city has changed, and “more and more towers are envisioned” in the core, Moore said.

In Washington, towers are largely absent because of the District’s height limits, but there are calls periodically to raise the limits. Two veterans of Washington planning—Harriet Tregoning, director of the New Urban Mobility Alliance, and Ellen McCarthy, principal in The Urban Partnership—made pitches during the Council for allowing somewhat taller buildings.

Tregoning called for allowing buildings as high as 200 feet on streets 160 feet wide. She said the District’s population, 521,000 in 1999, has risen to about 716,000, and in the face of fierce housing demand, “prices are crazy.” People of modest income, including many African Americans, are exiting the city. McCarthy said taller buildings could include some housing designated for lower-income people.

Thadani disagreed, saying that tall buildings, being more expensive to construct, are an unlikely source for many affordable units. “The only way you can get true affordability is in three stories and under—stick rowhouse scale,” he contended.

Justin Shubow, president of the National Civic Art Society, warned that a proliferation of taller buildings would undercut the visual appeal of a “fundamentally horizontal city.” Thadani concurred, noting that the city’s low skyline makes civic structures such as the Washington Monument prominent, even at considerable distances—upholding quintessential symbols of American democracy. “I can’t think of a major city that didn’t get taller and taller after eliminating height limits,” Shubow warned. As of now, the idea of raising the height limits faces considerable local opposition as well as resistance in Congress.

Even so, people have been adding two or three stories to the tops of many old townhouses. The lightweight pop-up structures are conspicuous along the city’s thoroughfares, and they often clash with the floors beneath them. They disrupt the coherence of the block. “In the last 15 years,” said Thadani, “DC has gotten uglier. A whole range of architects have completely ignored context.”

For a demonstration of how a mostly low-rise city—in this case Charleston, South Carolina—can add mid-rise structures and a substantial amount of building without harming the cityscape, Gary Brewer, a principal in Robert A.M. Stern Architects, presented Courier Square, a complex that uses traditional styles to reinforce the area’s historic character. Situated in the city’s Upper King Street Gateway district, Courier Square features multiple architectural expressions in historical styles; they visually divide Courier Square into segments and break down its bulk.

One part of the project is a five-story office building in Charleston’s 19th-century Classical tradition, ornamented with Greek Revival details such as Ionic columns. Butting up against it is a red brick apartment building called The Guild, which draws its esthetic from late 19th-century warehouses nearby. Some pieces of The Guild are five or six stories high; others extend to the eighth floor, topped off with pediments that add to the romance of the skyline.

Courier Square is in a new height district that the city established. A city review board allowed the project to have extra floors, based on its architectural merit. The use of multiple architectural expressions, said Brewer, has proven effective technique for adding density in a satisfactory way, in a community that values its heritage.

1 For a concise analysis of “stumpies,” see Sandy James, “Why Mid-Rise ‘Stumpies’ Are Everywhere,” Viewpoint Vancouver, Feb. 20, 2019.

2 Anna Kode, “America the Bland,” The New York Times, Jan. 20, 2023.

3 Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, p. 203 (footnote).

Access videos of presentations at the Density Without Urbanism/Urbanism Without Density council here.