The morbid and mortal toll of sprawl

A federal report this week revealed that traffic deaths have risen 9 percent over the last year and have totaled 19,100 in the first six months of 2016. More than 2.2 million people have been seriously injured in that time. The economic cost of those accidents is estimated annually at $410 billion, or 2.3 percent of gross domestic product.

The human cost is harder to calculate. Although motor vehicle accidents rank around 10th in causes of death in the US, they are the most frequent reason for fatality of children 5 and up and young adults. In terms of life years lost, motor vehicle crashes rank near the top—in this study, third behind coronary attacks and strokes.

Much of the blame has been placed, predictably, on distracted and drunk driving and rising vehicle miles traveled. The “elephant in the living room,” the factor that nobody wants to talk about, is sprawl and the infrastructure of sprawl.

The roads built to support sprawl, designed to modern safety standards, are contributors to the majority of US traffic deaths and injuries. A study by Garrick and Marshall of 24 small-to-medium-sized California cities highlights this issue dramatically. Twelve of these cities are mostly built on pre-1950 street grids. Those cities have less than one-third the traffic deaths per capita as the other 12 cities, with modern thoroughfare networks.

This study aligns with everything we know about the location of traffic deaths in the US. Cities like Boston, San Francisco, and New York have rates of traffic fatalities that are roughly a third of the US average. The reason is simple and straightforward. We have designed and built thoroughfares for 50-plus years to allow drivers to feel comfortable driving carelessly. These thoroughfares, built with “forgiving design,” encourage drivers to step on the gas in highly populated urban areas, and pure physics increases stopping distances and impact forces geometrically. This design approach also sets the stage for complete automobile dependence, causing more people to drive more in more dangerous conditions.

This has been studied extensively and verified for two decades. We don’t talk about it because the nation—and Departments of Transportation, planners, and engineers in particular—would have to face how badly we erred since the middle of the 20th Century.

If you examine the top reasons for loss of life years, most of the causes can be explained in terms of lifestyle choice like smoking, exercise, and diet. But the research tells us that crashes are largely related to how we built the infrastructure. (How much exercise we get is also related to the infrastructure, but I’ll leave that for another story).

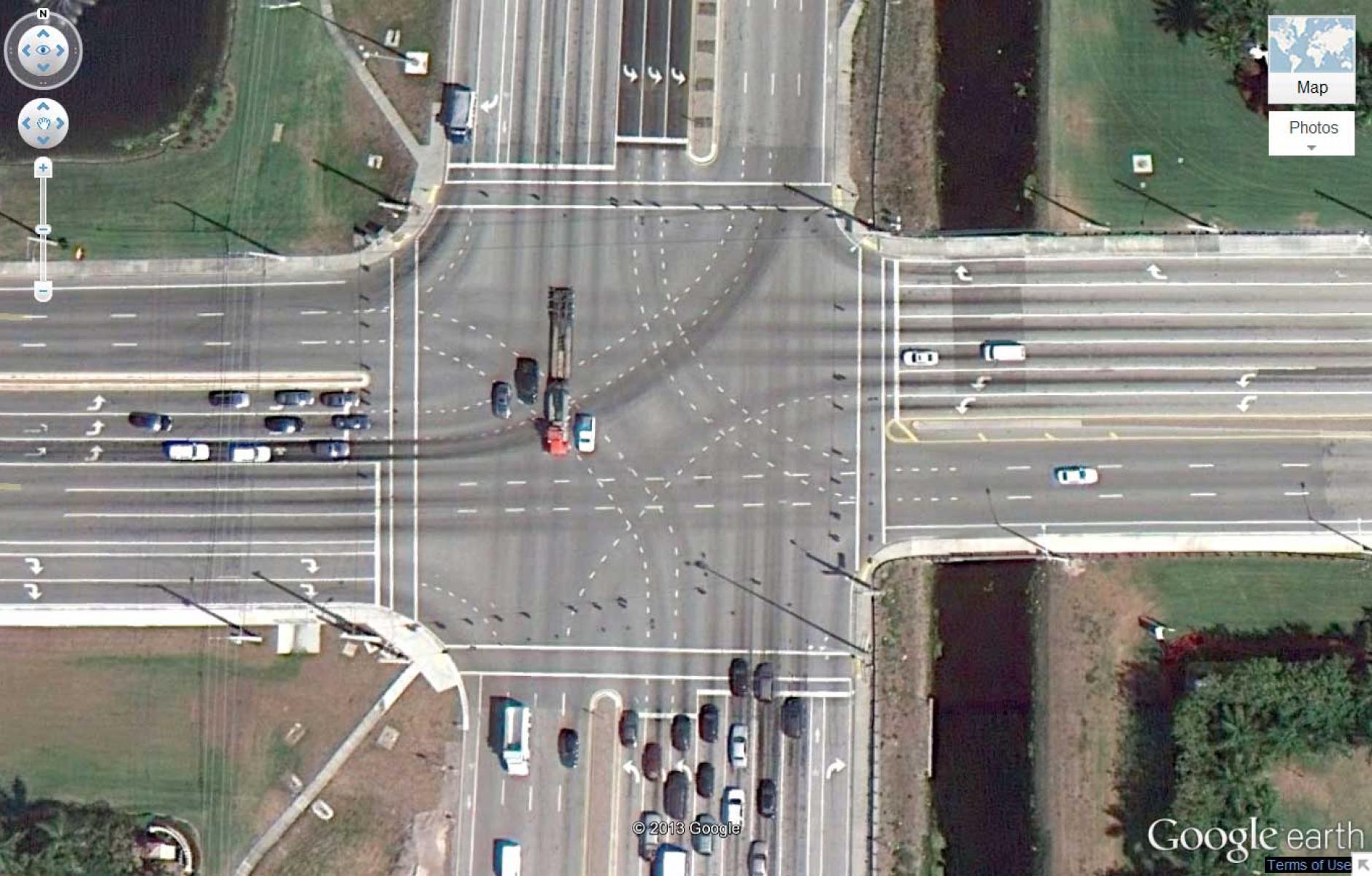

Ironically, we build thoroughfares that lead to death and injury in the name of safety. Wide thoroughfares and enormous intersections, which greatly increase speeds and are deadly to pedestrians, for example, are “justified” by safety concerns. That’s our federal, state, and local tax dollars at work. In a recent Public Square article, Vince Graham offers a succinct history of how this wrong turn in transportation occurred.

We dance around the issue. We talk about “complete streets” and rarely build them. Most of the complete streets projects are located in cities and towns with historic street grids—these thoroughfares were generally safer to begin with. Significant progress has been made on manuals to guide thoroughfare design, including the NACTO Urban Street Design Guide, the CNU/ITE Designing Walkable Urban Thoroughfares: A Context Sensitive Approach, and the Florida Complete Streets Implementation Plan. Transportation planners and engineers are justifiably proud of these documents, but manuals are the easy part.

Building and rebuilding safer streets that provide transportation choice throughout most of our metro areas is much harder, and we have barely scratched the surface on this project. I don't think we have admitted to ourselves the enormity and necessity of this task. As a consequence, look at how badly the US has lagged behind every other developed nation since the turn of the millennium on improving road safety. (Data from 2015 and 2016, not included in this graph, shows we are retreating on whatever progress we have made).

"Our complacency is killing us," said Deborah A.P. Hersman, the National Safety Council's president and CEO. "Americans should demand change to prioritize safety actions and protect ourselves from one of the leading causes of preventable death."

So the next time you pick up your car keys to take a drive on the nearby arterial road, try not to bump into the elephant on the way. Elephants can be dangerous.