Transforming a commercial strip corridor

How can a complete community be built around a late 20th Century commercial strip corridor? That's a key question in fragmented American suburbs coast to coast. Tukwila, Washington, aims to transform a mile-long stretch of Tukwila International Boulevard (TIB)—a vision explored in a three-day "Legacy Project" of the Congress for the New Urbanism in late February.

Tukwila is a diverse, growing, immigrant-rich community with no walkable downtown—but it does have a bold comprehensive plan. "The big story is not what we did, but what the city has already done to decide on a vision," says Susan Henderson of Placemakers, whose firm led a team of top new urbanists working with citizens and city officials.

"The Legacy Project was a wonderful opportunity," says mayor Allan Ekberg. "The timing was perfect, and it would have taken us much longer to do the public outreach on a project like this. I don't think we could have done it without CNU."

The program, in its third year, applies CNU’s renowned placemaking expertise to make a difference in the Congress's host region—in this case Seattle. Legacy Projects have achieved a remarkable track record of success—resulting in relatively rapid implementation in most locations where they took place in Dallas and Detroit, the previous two Congress host cities.

The challenge at the heart of the growing, 20,000-population Tukwila is its wide, 40-mph former state highway that was designed to primarily move automobiles and is lined largely by parking lots of businesses and shopping centers. By the standards of walkable cities and towns, the scale of the blocks are enormous. The city had already installed curbs, sidewalks, and street trees on the thoroughfare—but these improvements were not enough to slow down the traffic and create a main street environment. Little development resulted. "We thought we could build it and they will come—they didn't come," Ekberg says.

Tukwila has a lot going for it: Including a growing economy bordering Seattle, connection by light rail to the city, and visionary leadership that is not afraid of change. "CNU brought technical skills, but these folks have a vision that they believe in and are willing to make whatever decisions necessary to implement that vision," says Henderson.

Significant economic development could occur if targeted policy and infrastructure changes are made to create a walkable, main street setting.

Road diet

The first step is re-striping the thoroughfare, which is used by 12,000 to 18,000 cars per day. The road currently has five lanes—including a center turn lane—and is 62 feet across travel lanes, a long and dangerous journey for pedestrians.

Engineer Paul Crabtree proposed drive lanes be narrowed and reduced to three—cutting the crossing distance of travel lanes to 32 feet (see rendering below). In exchange, he recommended adding protected bicycle lanes and parking on both sides of the street, buffering people and bicyclists from the motor vehicles.

"We are proposing to balance the modes on Tukwila International Boulevard by changing it from 7 lanes to 9 lanes," Crabtree explains. "In other words, 5 Driving Lanes and 2 pedestrian lanes (sidewalks) are retrofitted to become 3 driving lanes, 2 bike lanes, 2 parking lanes and 2 pedestrian lanes—plus a number of new crosswalks."

The challenge is funding—because some intersections will need stop signs or stop lights. Ekberg estimates $200,000-250,000 per intersection that require signalization. Traffic studies will have to be conducted prior to implementing the changes, which are designed to minimize time and cost. Signalization aside, the thoroughfare can be transformed by paint, Crabtree notes.

Safety is a big potential payoff. From 2007-2011, 353 collisions were recorded, or one every five days. During the 10 years from 2006 to 2015, two pedestrians died on this stretch. The proposed streetscape is designed to reduce speeds and the severity of crashes.

Code reform

Placemakers recommended strategic changes to the zoning code. The city had suggested that a full form-based code (FBC) is needed, but Placemakers said less expensive and simpler changes would suffice for now in this suburban retrofit environment. The firm recommended five adjustments to the code in the study area: The adoption of "built-to" lines to create a sense of enclosure, reduced parking requirements, regulation of parking location for new buildings (to the rear and side), simplification of the use table, and making mixed-use legal by right.

Code adjustments could also address a systematic problem of large block sizes. The typical "Tukwila block" is 20 acres, about 20 times the size of blocks in Portland, Oregon, and 8 times the size of Seattle urban blocks. Architect Steve Mouzon, a charrette participant, suggested that rights of way could be required along certain lot lines to allow blocks to become smaller over time. The tradeoff for property owners would be mixed-use and more development rights.

Incremental development

With streetscape improvements and adjustments to the code, incremental growth could occur. Retail expert Robert Gibbs reports that new development on the corridor is stalled due to lack of walkability and poor urbanism—but the city has strong un-met demand for restaurants and neighborhood goods and services, especially daytime restaurants. "Our study found a walkable mixed-use town center could support nearly 50,000 square feet of new retail and restaurants generating $13 million in new sales," Gibbs says.

The demand for housing is strong, too, according to market researcher Laurie Volk of Zimmerman Volk Associates. Over five-years, between 405 and 502 rental and for-sale housing units can be supported within the study area, she says. The mix could include 305 to 380 rental apartments, 15 to 20 condominiums, and 85 to 110 townhouses.

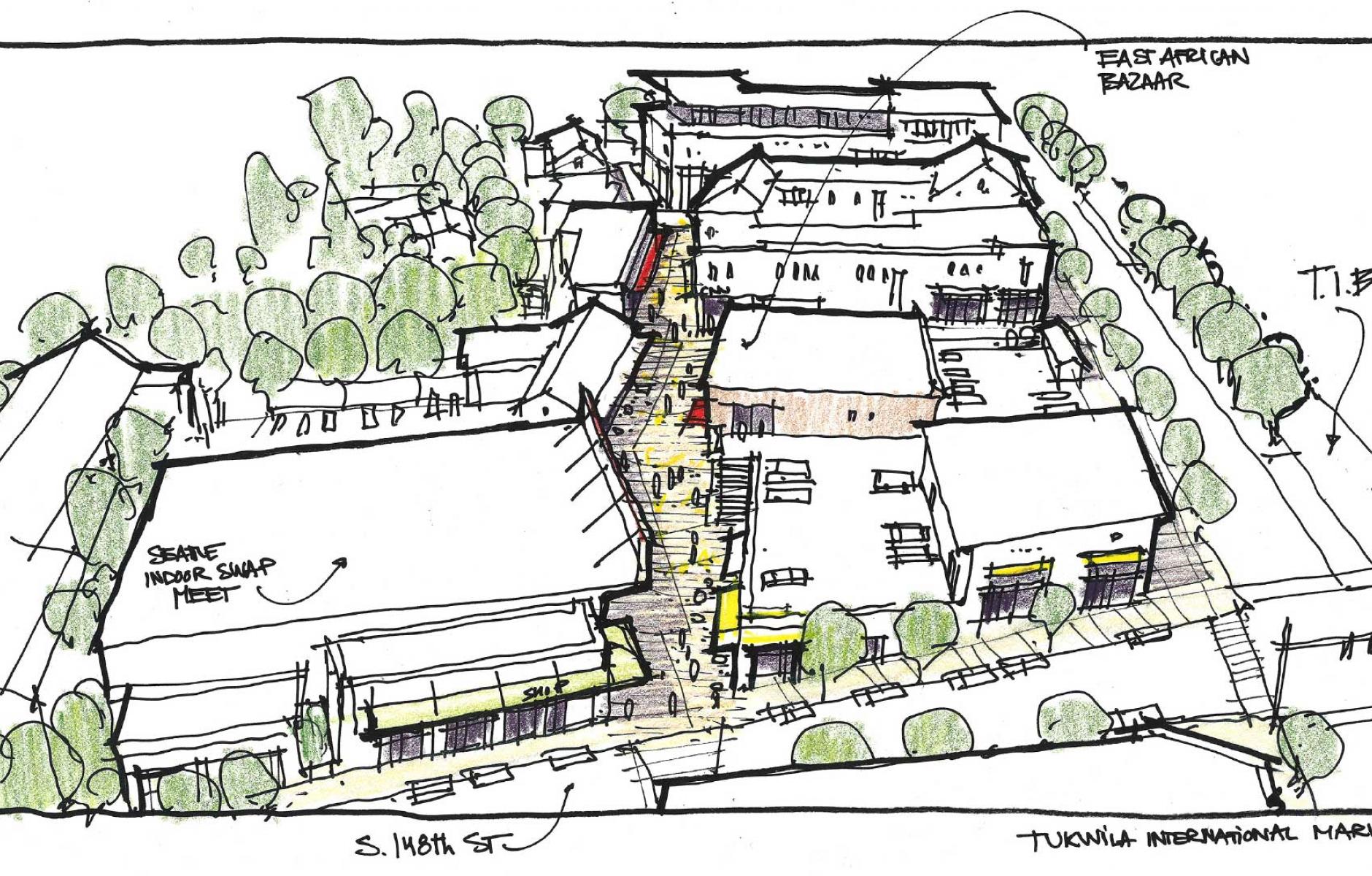

Two major projects were examined—one of which could be built incrementally. TIB currently benefits from ethnic retailers serving Asian and African immigrants. The planners showed how a strip shopping center parking lot at 148th Street could be infilled to create "bazaar-like" urban place that might become a regional draw (see rendering at top of article). Plans and renderings were drawn by Andrew von Maur of Andrews University and Fikreab Abaata, an African immigrant and graduate of Andrews working for Fuller Sears, a design firm.

A transit-oriented development on a 600-lot surface parking lot of the Sound Transit light rail station would require substantial capital, because the park-and-ride is heavily used. Parking structures would free up land for mixed-use development. The parking area is currently a hotbed of petty crime, and mixed-use development could solve that problem with 24-hour "eyes on the street," planners note. A "transfer plaza" would allow pick-up and dropoff of riders.