The urban anxieties of Richard Florida

When Richard Florida burst onto the North American scene nearly 20 years ago, he did so with a sunny urban vision.

His breakthrough book, The Rise of the Creative Class, asserted that a growing class of knowledge workers, techies, artists, and other creative people was gravitating toward city districts that offered “a vibrant ‘quality of place.’” He believed that as these talented folks settled into locales that welcomed diversity and contained great restaurants, pedestrian-friendly streets, bike lanes, and other appealing features, a “more inclusive urbanism” would take root.

Over the past several years, however, Florida, director of the University of Toronto’s Martin Prosperity Institute for the past decade, has turned gloomy, churning out studies and commentaries warning about worsening disparities in the cities where most of the high-paying creative jobs are concentrated.

Now his darkening view is elaborated on at book length in The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can Do About It (Basic Books, 336 pages, $28 hardcover). “As I pored over the data,” Florida writes, “it became increasingly clear to me that only a limited number of cities and metro areas, maybe a couple of dozen, were really making it in the knowledge economy.”

The encouraging news—to the extent that Florida delivers encouraging news any more—is that demand for lively, walkable neighborhoods is burgeoning in the US and Canada. The creative sector is strong, and Florida reports that “the advantaged knowledge workers, professionals, and media and cultural workers” earn more than enough to live in pedestrian-friendly, amenity-rich urban settings.

The converse, he says, is that “members of the two less advantaged classes—blue-collar workers and service workers in jobs like food preparation and office work”—are being left out. Those two classes have lost economic ground when the price they pay for housing is taken into account. Increasingly they cannot afford to live near the vital hubs of the knowledge economy. In New York, the average creative-class worker has $71,245 of annual income left over after paying for housing, but the average working-class person has only $27,343 left over and the average service-class worker has a mere $17,861. No wonder inequality has become one of the pressing issues of our time.

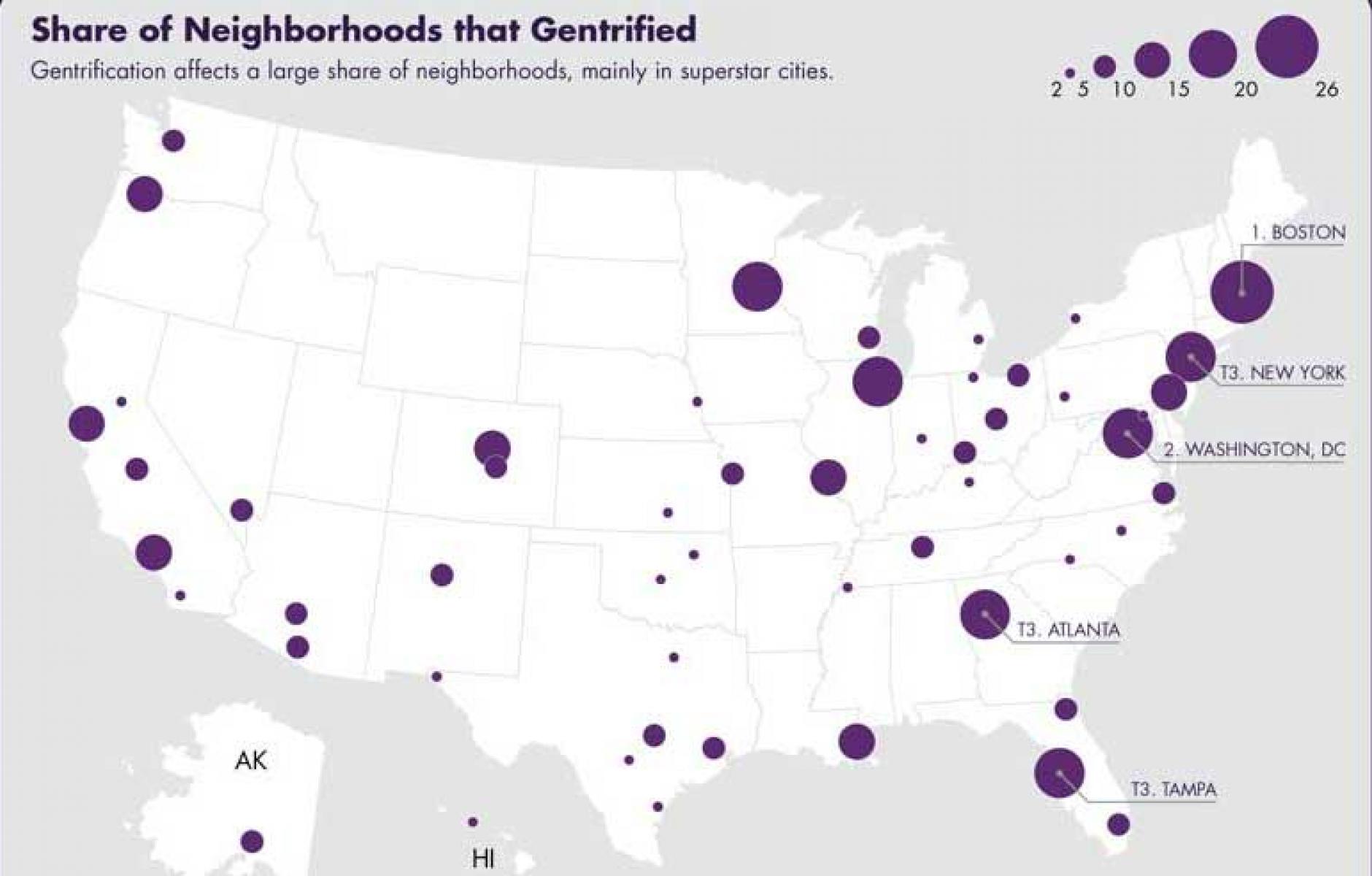

The clustering of talent and economic assets in cities is benefiting “the already privileged, leaving 66 percent of the population behind,” Florida says. “Left unchecked, this clustering force generates a lopsided, extremely unequal kind of urbanism in which a relative handful of superstar cities, and a few elite neighborhoods within them, benefit while many other places stagnate or fall behind.”

Florida is a whiz at statistics. He has packed this book with charts and tables that document a large and growing gap between rich and poor; geographic segregation of people with low incomes or modest education; segregation of college graduates; segregation of wealthy residents; and segregation of the working class and the service class. His maps show how these disparate groups sort themselves out in a dozen large US metropolitan areas and in Toronto, Vancouver, and London as well.

In the economically least advanced parts of the world, the situation is even grimmer. “For a billion or so urbanites in the developing world, urbanization is a near total failure,” says Florida. Exploding populations are overwhelming the capacity of Third World cities, he observes, with the result that “tremendous numbers of new migrants end up being packed into rudimentary settlements in mega-slums.”

What has arrived, Florida says, is “winner-take-all urbanism.” I’m glad Florida pursues his subject so intensely, and yet I’m bothered that he paints with such a broad brush. Readers of this book may come away thinking that American urban revitalization has been a failure, because it has rendered city life too expensive for many people—which is not true in every city. Though people of modest income are being priced out of large swaths of superstar cities such as New York, San Francisco, Washington, and Boston, the situation is different in many smaller cities and in metro areas where the economy chugs along at a moderate pace. There urban revitalization remains a largely positive force; I hate to see Florida disparage it.

For a book on walkable communities, I recently spent time getting to know a few neighborhoods on the periphery of Center City Philadelphia. All of those “Greater Center City” neighborhoods have become safer, better maintained, and more generously supplied with restaurants, cafes, stores, and welcoming public spaces in the past 20 years. Housing costs in those neighborhoods have gone up, but still, they’re not in the same league as New York, San Francisco, and Florida’s other “superstars.”

One neighborhood I studied is a slice of traditional South Philadelphia that’s now called Southwest Center City—the result of its becoming more fully absorbed into the economy and life of Philadelphia’s wonderful, resurgent core over the past 30 years. Southwest Center City had 1,754 vacant homes, a backlog of neglect, and 12,400 inhabitants in 1980—less than half the population that it possessed in the 1930s. Today it has rebounded to 15,000 residents, and it has few vacant buildings, numerous new or rehabilitated houses and apartments, and congenial, well-used public spaces.

People in their twenties and thirties abound in the neighborhood. Rent a small rowhouse in Southwest Center City and you’re only a 20-minute walk (or a 10-minute bike ride) from the plaza in front of City Hall, the center of downtown. The new residents have pitched in to clean the streets and to improve the neighborhood’s public elementary schools—through tutoring, enhancing of buildings and grounds, and creation of a first-of-its-kind outdoor space for teaching science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. The schools, predominantly attended by African-American children from low-income families but also by an increasing number of middle-income whites, have seen their educational performance perk up.

Some poor residents have moved out as rents climbed. But many residents have stayed. A 2015 study of gentrification, for the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, found that most of the existing residents in the Philadelphia neighborhoods that are revitalizing have remained in those neighborhoods. And the economic status of many of those residents has improved. Murray Spencer, a black architect who has lived in Southwest Center City for 41 years, mostly in a rowhouse near a YMCA where a teenaged Wilt Chamberlain distinguished himself on the basketball court, says the Edwin M. Stanton Elementary School on his block “has become a good school. ... In my neighborhood unlike the city as a whole, people are generally happy with the schools.” A new energy is manifest.

My sense is that this phenomenon holds true, to varying degrees, in many cities. Early in his book, Florida writes of “rampant gentrification and unaffordability, driving deep wedges between affluent newcomers and struggling longtime residents,” but that’s the case, as he later clarifies, mostly in cities with superheated economies, not in the much greater number of cities where change is gradual.

What can be done about rising inequality? Among Florida’s recommendations:

- Spend public funds, including fuel tax revenue, on mass transit rather than highways, to help low-income people get to jobs in central locations.

- Establish a land value tax to prod property owners to put their land “to its most intensive use.” This could generate additional housing in walkable centers.

- Redirect federal housing subsidies away from affluent homeowners and toward “less advantaged renters who really need them.”

Raise the incomes of low-income people so that they can afford better housing. “If we want to build a new middle class, we have no choice but to turn the millions of low-paid service jobs we are stuck with into higher-paying jobs,” Florida urges.

He touts high-speed rail, but it’s not clear to me that super-fast trains could carry enough workers to exert a large impact on a region’s economy—and also deliver them at a reasonable cost.

The least useful recommendation is establishment of “a high-level advisory group on cities—a President’s Council on Cities ... to set and coordinate urban policy across the administration and federal departments and agencies.” Evidently Florida stopped writing before last Nov. 8.

Mostly, Florida offers policy ideas. He takes a top-down approach, seeing urban neighborhoods through a distant telescope rather than close up. What’s missing are the kinds of things that individuals, neighborhood groups, and local organizations can do on their own, or mostly on their own.

Shouldn’t we be paying heed to grassroots methods? I’m intrigued by approaches like those presented by the Portland, Oregon-based developer and consultant John Anderson in a blog post called “Gentrification? Nah. Let’s talk about local jobs and local wealth.” Instead of waiting for big government policies, Anderson suggested “cultivating the local building trades.” Addressing small developers, he said:

Chances are the plumbers, framers, electricians, drywallers, and roofers already live in the neighborhood you want to work in and they may be traveling significant distances to find steady work on large projects. What if you could provide a steady backlog of work for those folks right in their neighborhood? .... How many tradespeople are close to being able to open up their own shop if they knew they had steady work for their crew?

Maybe you introduce them to Janet the excellent local bookkeeper who knows Quickbooks and how lien releases and trade credit works. Small business people doing favors for each other can go a long way toward building local wealth and local jobs in the neighborhood. Maybe you guarantee their first line of credit at the lumberyard for a year to help them get on their feet. ... Building local wealth and local jobs could start with you in the place you are committed to.

Expanding on Anderson’s idea, now suppose that those small operators look in the neighborhood for talent they can train and hire. Maybe some of the talent can be found among the modest-income individuals who are at risk of not being able to afford the neighborhood’s rising rents. If they could become part of an interconnected, very local economy and society, some of our problems with displacement and inequality might begin to soften.

I’m not saying that Florida’s ideas are wrong. But I think that in addition to pursuing national policies, we have to devote an equivalent volume of energy to encouraging local communities to cultivate their own skills, generating jobs and income by harnessing the potential of their residents. Maybe some communities are too disorganized or dispirited to do this. But surely some locales can follow Anderson’s prescription.

Think small. Think local. Look for opportunities close by. Don’t wait for a distant savior. He may not show up, or his policies may turn out to have ill effects.