Pontiac loop highlights a national infrastructure need

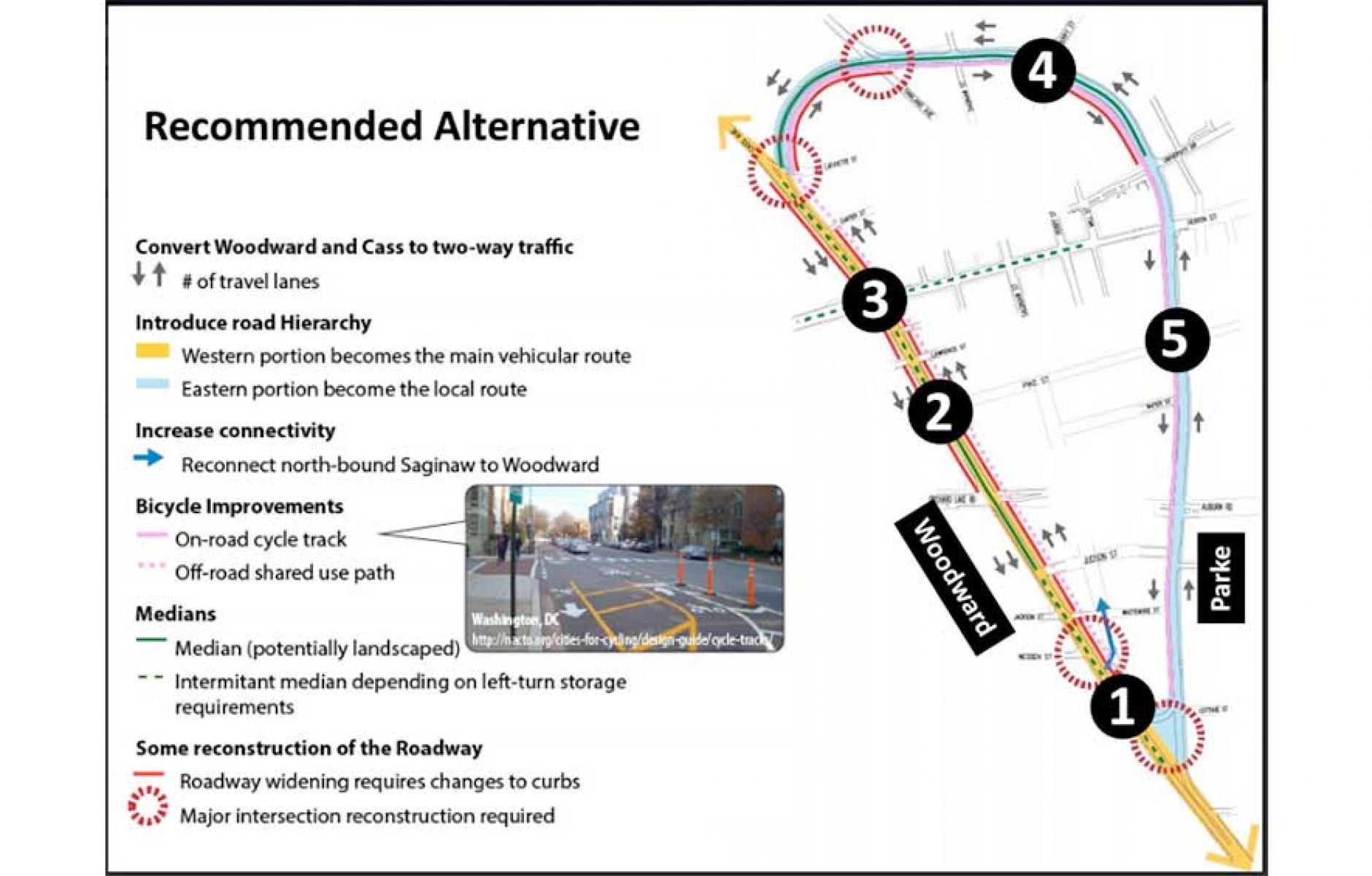

Pontiac, Michigan, is moving forward with plans to revert a 2.5-mile one-way loop to two-way traffic—a change that is projected to bring 200,000 square feet of retail and $55 million in annual sales to the City's distressed downtown.

The plan, in the works for 15 years, was given a boost by a CNU Legacy Project that began a year ago prior to the 2016 Detroit Congress, when a team of planners led by DPZ Partners refined the plan and linked it to a larger vision for downtown.

Some challenges remain to implementing the loop reconstruction, which would cost $15-20 million—and they highlight a larger infrastructure issue facing Michigan's DOT and others around the US. Funding and decision-making practices deep within these organizations are holding back the revitalization of cities and towns.

According to a recent report in Metromode (Undoing the 'catastrophic mistake' of Pontiac's Woodward Loop), MDOT only considers three issues to trigger project funding: Congestion, safety, and deterioration of roadway. But the primary reasons to redo the Woodward Loop relate to economic development and livability, says Sandy Montes of MDOT, The department lacks a "template" for the reconstruction, she says. On the contrary, there are potential safety benefits from changing to two-way traffic from one way. The Woodward Loop is wide, with fast-moving traffic, and by all accounts uncomfortable for pedestrians to cross. From 2004-2013, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reports three deaths on the Woodward Loop, including one pedestrian.

Be that as it may, the idea that MDOT does not consider economic development or livability important funding criteria misunderstands the function of thoroughfares in walkable cities and towns. Urban streets are public space—a vital part of the public realm. They support commerce, social interaction, physical activity, recreation, and multimodal transportation. MDOT's funding criteria are stuck in a limited, mid-20th-Century view of thoroughfares.

Like most cities, Pontiac benefited from a fine-grained network of blocks and streets connecting downtown to surrounding neighborhoods for most of its history. In a move that everybody in the city now acknowledges was a mistake, the city and MDOT built the Woodward Loop around downtown in 1964. Oakland County planning director Bret Rasegan described the loop as "well intended" in an interview with Metromode.

"They thought it was good for broader regional traffic flow as well as good for the businesses, but ... unfortunately, in hindsight, we feel that it harmed the downtown by creating that barrier and cutting the neighborhoods off from downtown," Rasegan says.

Along with "urban renewal" projects during this era and other policies like minimum parking requirements, most historic downtown buildings were demolished. The city lost population in every decade from 1970 to 2010. The population has since stabilized and crept up, concurrent with national back-to-the-city trends.

Yet in order for downtown revitalization to begin in earnest, the city needs to undo some of the damaging planning decisions of the last century. Metromode relates how the this issue affects local developer Kyle Westberg:

The evolution of Westberg's Lafayette Market business more or less summarizes the common argument against the Woodward loop, which encircles downtown Pontiac. When Westberg opened the shop downtown in 2012, it included a cafe and a full-service grocery store. The cafe is still doing well today, but the grocery store has been pared back to just a beer and wine department.

Westberg says that's at least partly because Pontiac residents simply don't want to deal with the hassle of circumnavigating downtown on the Woodward Loop or attempting to cross it on foot, to get to his store. They're more likely to head out to big-box stores on the city's fringes than to shop in their own downtown. "(The Loop) turned a nice, loveable downtown into a racetrack to get cars around," Westberg says. "It's been bad urban design from day one."

Pontiac is a case study in why street design and construction policy and practice needs reform. MDOT has a lot in common with DOTs across the US where planners and engineers are experienced and comfortable with thoroughfare projects geared to moving automobiles at the expense of other vital functions. The Woodward Loop reconstruction has been supported locally since 2001, but MDOT has blocked progress. Now MDOT's willingness to cooperate indicates change is on the horizon.

"I would hope we can find the funding quickly, but it's hard to say," Montes told Metromode. "This is a unique project, and it's going to take some creativity."

Yes and no. The Woodward Loop is similar to thousands of needed projects in towns and cities nationwide, where outdated mid-20th Century street projects need reconstruction. These projects could unleash a torrent of economic activity and quality of life benefits. That's worth considering as the nation gears up for a trillion-dollar infrastructure upgrade.