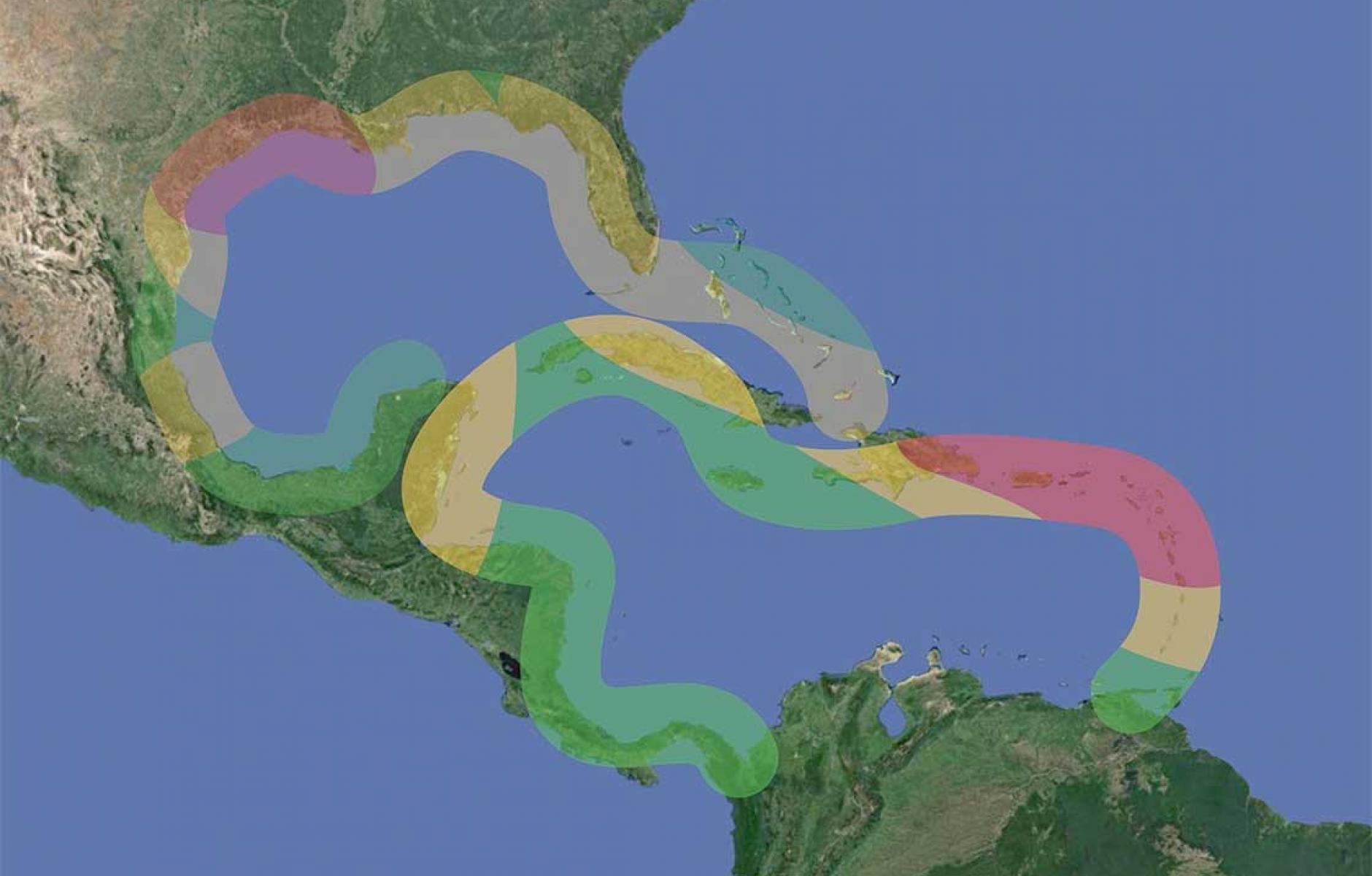

The great Caribbean Rim rebuilding challenge

As Caribbean Rim nations move from emergency relief to disaster recovery mode in the coming weeks and months, strong consideration should be given to the ways in which places should be rebuilt, both at the scale of towns and of buildings. This, the worst hurricane season in twelve years, has caused too much pain for too many people for everyone to go back to the ways things were before. The Caribbean Rim has had severe storms for all of recorded history, but many of the lessons our ancestors learned the hard way have been lost over the past century, as we moved from building in harmony with nature to trying to engineer our way out of severe weather problems.

Sustainable communities

Sustainability begins at the scale of urbanism, because it makes no sense to talk about sustainable buildings until the place itself is sustainable. The lone surviving building in an uninhabited town isn’t a very good place to be.

Storm surge

The first question to ask is “should we be building at all in this place?” This is especially difficult in a once-inhabited place that has been severely damaged, because it’s so hard to tell someone they can’t come home again. But the fact of the matter is that storm surge is one of the most destructive forces in nature, which building structures are almost powerless to resist. Strong storm surge almost always reduces buildings to piles of rubble, and usually kills more people than wind in a hurricane.

The good news is that storm surge risk is no longer a mystery, as we now have a good understanding of how the forces of nature and undersea topography affect the risk in any given place. Often, safer places are on higher ground within sight of surge-prone areas. Sometimes, it may be necessary to move a settlement a few miles away, but in no case should people return to places known to be at high surge risk.

Dunescape

A healthy dunescape is the first line of defense against a storm. Sadly, developers forgot that fact for decades and built right on the dunes in many places. When Hurricane Opal slammed the Florida Panhandle in 1995, many buildings in the vicinity Seaside, Florida were completely demolished, whereas Seaside was virtually untouched. Hurricane experts came to study what happened, and dubbed it the “Seaside Miracle.” The secret? Yes, the buildings at Seaside were built to stronger standards, but more than anything else, Seaside stepped back from and protected the dunes, unlike many of its neighbors. Hurricane Ivan hit further west in 2004, but still, buildings east of Seaside sitting on the dunes were destroyed while Seaside again experienced almost no damage.

Stepping back and not building on the dunes is only the first step, however. To sustain the dunes, it’s essential that they become diverse biomes instead of monocultures of single plants. Invasive species such as scaevola (sea lettuce) and casuarina (Australian she-pine) take over dunes and then destroy them. The best and most sustainable dunes have about twelve species of well-adapted plants, from grasses and ground cover to palm trees.

Agriculture

Until the mid-20th Century, most Caribbean Rim towns were fed from the fields and waters nearby. Now, most places on the Caribbean Rim and elsewhere are fed from thousands of miles away, and the shutdown of a single port facility such as the one in San Juan, Puerto Rico can result in food and other urgently-needed supplies not reaching those who need it most. Yes, a hurricane will damage the local crops, but if people have a choice between walking out into the fields and picking and eating what’s left of a crop today, or waiting for a ship to come in and get offloaded days (or longer) from now, which is more survivable?

Compact towns

The benefits of compactness run far beyond the scope of this post, but some of the most obvious are as follows:

• Compact towns place buildings closer together, where each building helps shield its neighbor against hurricane winds.

• Buildings that are attached such as in downtown Nassau, Havana, and pretty much any Spanish colonial town are substantially stronger than buildings standing alone.

• Town centers with many attached buildings really should be built of masonry to resist fire spread, and masonry buildings are inherently stronger against the wind than framed buildings.

• Compact towns get electricity back quicker. We evacuated for Irma, and from the time we were allowed back onto Miami Beach until we got our power back was less than 24 hours. Last week, Wanda and I were in west central Florida near Apopka, and there were still many power lines down. This must ever be so, as utilities naturally try to get power back to the greatest number of customers as soon as possible, and that naturally happens where customers are closer together.

• Streets are walkable before they’re driveable. You can clamber over a downed tree on foot, but not in a car. If the town is compact enough, you can get to more necessary things sooner, by hours or more likely days.

• Fuel supplies in catestrophically-damaged places may be cut off for weeks, if not longer. Vehicles that survive the storm are of little use so long as they are out of gas. People in walkable places fare much better.

Small local businesses

Town economies built mostly on small local businesses tend to be more resilient than those filled with multinational chain operations for reasons we’ll explore in more detail in a later post, but some of the biggest reasons are:

• A local businessperson is far more motivated to get back in business because their livelihood depends on it, whereas to a multinational corporation, their location in town is just one of many around the globe.

• Decisions about whether and how to reopen a chain operation must be run up the chain of command to at least the regional level, which on the Caribbean Rim might be someone in another nation. Local businesses, on the other hand, need only find the basics like drinking water and fuel before they can start selling whatever is left of their stock of products.

• Chain stores tend to be larger, fueled by international business size standards and the myth that bigger is always better, whereas many local businesses on the Caribbean Rim are single-crew workplaces. Smaller operations have fewer employees (if any) and fewer moving parts necessary to get back in operation.

Local leadership and culture

This will be the topic of an entire upcoming post, but should be mentioned here as well. A town led by local leaders and guided by local culture is far more sustainable than a resort managed by an offshore corporation. The Caribbean Rim is littered with the bones of failed resorts, with hurricane damage being the most frequent cause of their demise. The outnumber Caribbean Rim ghost towns, even though people have been builiding towns for centuries longer than they have been building resorts.

Sustainable buildings

Once a town is planned or replanned sustainably, it’s time to consider how to build or rebuild the buildings. A Living Tradition [Architecture of the Bahamas] is a detailed pattern book showing how to build sustainably in the Bahamas, and most of the lessons from that book are useful around the Caribbean Rim.

Beloved buildings

Almost everyone wants to put things back the way they were after a disaster. Their new home should look and feel like their old home. Unfortunately, many in my profession (architecture) want to remake the new world into something very different. This rarely succeeds, and even when it does due to a major source of outside funding (such as the Make It Right houses in New Orleans) it does not spread to surrounding neighborhoods simply because it doesn’t feel like home… it feels like something foreign. New buildings in Puerto Rico should not feel like they’re from Atlanta; they should feel Puerto Rican. New buildings in Barbuda (if the island is rebuilt) should not feel like they’re from Orlando; they should feel Barbudian. Not only do they help people recover emotionally from their losses, but they are more likely to be cared for and restored long into an uncertain future.

Buildings that endure

Hurricane Design is a post that lays out several strategies for stacking the deck in your favor with building design. Here’s a quick summary of the top ten strategies:

• Build hip roofs on all but the smallest or strongest buildings to be wind-strong so each side supports its neighbors.

• Pitch wind-strong roofs 8/12 to 9/12 because this is steep enough to resist uplift but shallow enough to resist overturning.

• Overhang wind-strong eaves less than you would inland eaves so there’s less for hurricane winds to grab.

• When long eaves are necessary in the tropics, design them to blow off, leaving the main roof intact.

• Long eaves on wind-strong buildings can be supported by heavy brackets.

• Properly-attached metal roofing is the best material for a hurricane zone.

• Shutter windows in some way so that most if not all of the opening is protected with the shutters.

• Choose carefully between wood walls and masonry walls in a hurricane zone; each has its strengths.

• Build above the floods in a hurricane zone so the storm surge does little or no damage.

• If piers are masonry build them thick, or if wood, drive them deep so that they resist storm surges.

Kernel Cottages

Andrés Duany and I came up with the idea for the Katrina Cottages in 2005, on the Saturday after the hurricane. The original idea was to design “FEMA trailers with dignity,” but we quickly realized that with the money FEMA was spending to manufacture, install, commission, maintain, decommission, haul away, and dispose the FEMA trailers, we could design cottages worthy of being there for a hundred years, not just the FEMA-mandated 18 months. This would allow people to get a foothold back on their property, building on later to create a larger house.

Or at least that’s what we said. In reality, the cottages didn’t expand very well. Because the cottages were so small (several under 500 square feet) the exterior walls quickly got gobbled up with cabinets, closets, bathrooms, and the like so that it was difficult to find a place to add on. I designed the first Kernel Cottage the next summer; the very first design move was to put four “grow zones” in the plan, from which the cottage could expand. Disaster recovery housing that is mobile need not do this, but cottages meant to stay should definitely incorporate easy expansion.

Frugality

People recovering from a disaster are usually stretched to the limit (or beyond) financially. Why spend a lot of money conditioning a house if it can condition itself on all but the most extreme days of the year? An upcoming post will lay out several self-conditioning strategies. And self-cooling isn’t the only way to be frugal; you can be frugal with interior space as well, so that a cottage is smart enough that it lives bigger than its footprint. The New Urban Guild calls these SmartDwellings, and these are some strategies for implementing them. The image on that page shows an elaborate 1,200 square foot SmartDwelling, but the frugality techniques can just as easily be used on smaller Kernel Cottages as well. As a matter of fact, that’s where several of the techniques were first developed. We’ll dive into a number of frugality patterns in a later post.

Please help

This and the next several posts are things I’m writing for the second edition of A Living Tradition [Architecture of the Bahamas], which I hope and believe will be useful around the Caribbean Rim. The Original Green is a far better book because of many great comments I got from readers of this blog as I was writing it. Please help make this second edition a better book as well by posting your insights here… it could benefit so many people whose lives have been so disrupted! Thanks in advance!

This post was originally published on The Original Green website