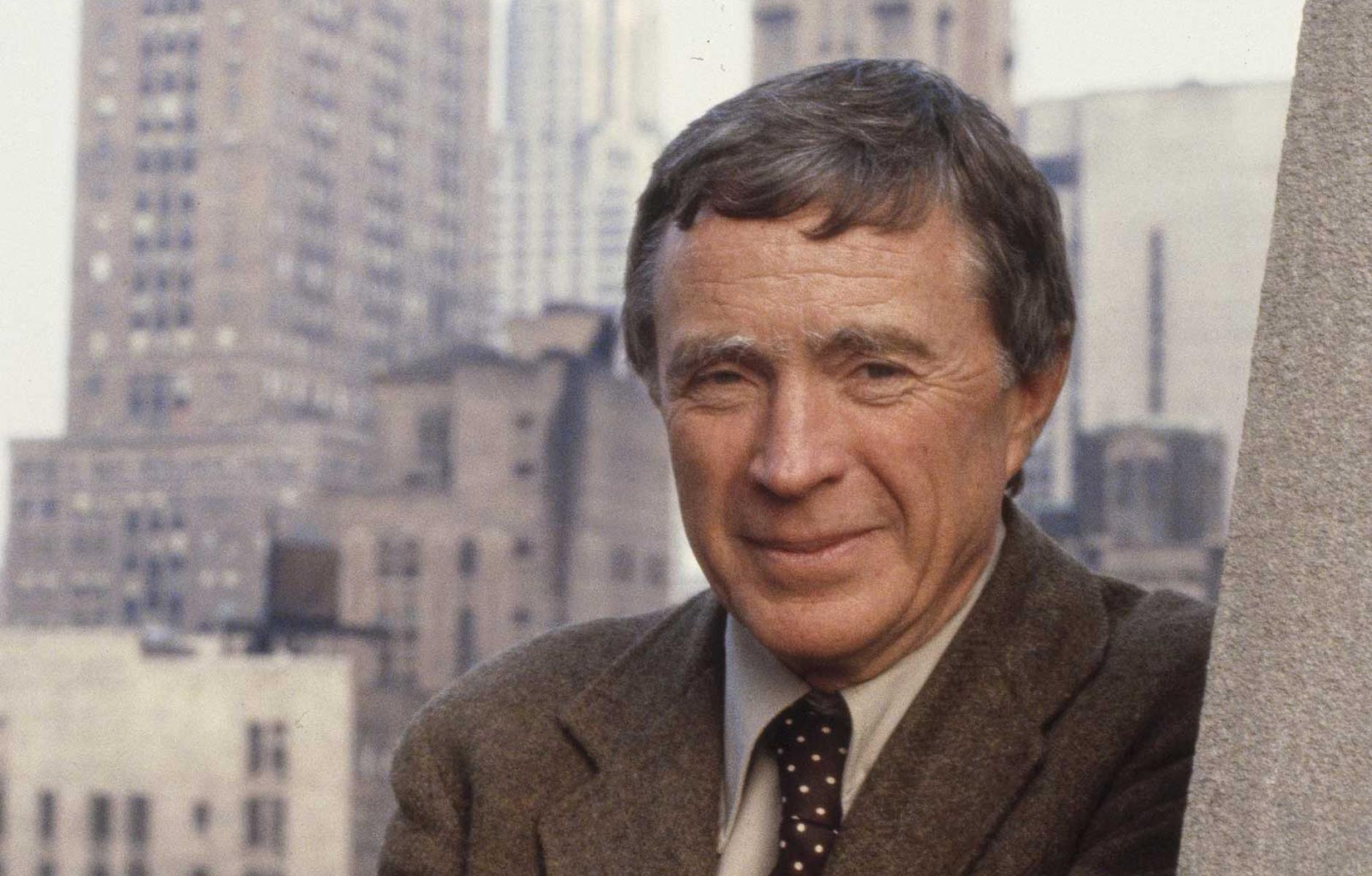

Vincent Scully, ‘spiritual father of the New Urbanism’

In late 2017 America lost an intellectual giant, a rare academic lecturer in the humanities who had a real impact on American communities in his lifetime. Architectural historian Vincent Scully, who taught for five decades at Yale and after retirement lectured at the University of Miami, was a singular force in keeping alive lessons from our architectural past when they were swept away in the tied of modernism. Scully died November 30 at the age of 97.

“During his half-century at Yale University, he left his mark on generations of consequential architects, from Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, and Robert A. M. Stern down to Maya Lin, Andrés Duany, and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk,” Matt Schudel wrote in The Washington Post. Schudel added: “Two of Dr. Scully’s students in the 1970s, Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, used his principles to develop a movement in architecture and planning called New Urbanism. With an emphasis on historic preservation and the idea that architecture could build a sense of community, Duany and Plater-Zyberk — a married couple based in Miami — seemed to have drawn their vision directly from Dr. Scully’s lectures.”

Scully's spellbinding effect was vividly described in a tribute this month by Michael J. Lewis of Williams College in New Criterion. Although Scully was a prolific writer, as a lecturer he was most influential, Lewis says. These were dual-slide-projector performances before Powerpoint, of the type often used by architects and academics, to large lecture halls packed with students.

“Most lecturers shift to the next image, pause for an instant, and then launch into a new set of thoughts. But Scully exploited the full potential of a visual presentation. His images advanced in mid-sentence, as if conjured by living thought—the visual and the verbal material moving together in a kind of musical unity,” Lewis writes.

Scully favored an oversized bamboo pointer that he wielded like Captain Ahab’s harpoon, striking the screen violently to call attention to a feature, Lewis writes.

“Scully’s eloquence poured out in a furious cascade of metaphors and similes, some of which found their way into his American Architecture and Urbanism (1969). Frank Furness’s Provident Life & Trust Building, for example, was “a great machine out of technology’s archaic beginnings, a cast-iron marvel by Jules Verne . . . a Philadelphia row house worked up into a paroxysm at once athletic and mechanical, a great golem of industrialization clanking away.” The Empire State Building, “a lonely dinosaur, rose sadly at midtown, highest tower, tallest mountain, longest road, King Kong’s eyrie, meant to moor airships, alas.” Most quoted is his lament for Pennsylvania Station: “Through it one entered the city like a god. . . . One scuttles in now like a rat.” If that station is ever rebuilt, which at this moment seems barely possible, a goodly portion of the credit will go to that offhand quip.”

Duany apparently was influenced by Scully's lecturing style as much as the message. Duany gave a mesmerizing lecture for 15 years with the dual-projector system that garnered countless converts to the New Urbanism.

Scully's enthusiasms changed over his lifetime, Lewis reports, from conventional modernism and Le Corbusier to Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi, "and finally to Duany and Plater-Zyberk, his own students and the leaders of the New Urbanism. What might seem at first glance to be unprincipled fickleness was in fact an expression of consistency on the part of Scully, who always identified himself with what he felt to represent the most humanist direction of architecture at any given moment." Along the way, Scully offended and horrified many guardians of current fashion and thinking.

I met Scully once, at Seaside in 1997, when The Seaside Prize was presented to mayor Joe Riley. Scully was the first winner of the Seaside Prize, along with his pupils Duany and Plater-Zyberk, in 1993. Jane Jacobs was the second winner.

The Vincent Scully Prize was established in 1999 by the National Building Museum to recognize exemplary practice, scholarship or criticism in architecture, historic preservation, and urban design. Scully was the first recipient.