Five steps to super blocks

Here's a step-by-step process to designing a piece of a city. Don't be put of by the design complexity and follow these steps, one after another:

1) Draw a truly large block—it doesn't have to be stiffly rectangular either; the best way to accomplish irregular blocks is to simply cover the space between streets!

Large blocks were located historically toward the edges of the city with urban edges and undeveloped fields in back of them, in the center of big blocks.

2) Draw lanes that naturally enter into the large center of the block and there create a central place (it doesn't have to be regular!). I always imagine that I'm drawing rural lanes dividing large fields.

You'll note that the lanes (once they develop as very narrow streets) form new small blocks. This is Leon Krier's notion of a “Block of Blocks” and (though his are a bit small) these subdivided blocks constitute much of the fabric of the traditional cities that we love.

3) Put in a parking alley between the outside frontage of the big block and the new frontage of the central place, then draw the lots according to the building types.

4) Shade (poche) the buildng fronts so that you know that you are in control of the making of space! Add a bit of color to show the the Transect according to your context and taste.

If you think of it as creating “nested” hamlets, or villages centers, market town armature and city fabric you'll get the types and the “feel” right.

You are well on the way to drawing a mature city with many centers of a great variety. Many varied “centers” are the key to long-term resilience. It's why Seaside is superior to later New Urbanists towns (it's not the architecture). Chris Alexander wrote that the more centers there are, the more human the environment. He's right.

5) By the way, you don't have to directly connect the alleys. And you don't have to connect the narrow lane/streets with the lane/streets of the neighboring complex block! It's how one creates the quiet streets of traditional fabric. Complex blocks allow the right-of-ways to really be different, not "this-one-has-only-one-parking-lane stuff" but differences that are articulate in plan and section.

Note and study the effects of your design. Voila! You know how to design a sophisticated city!

Finally, a secret: this step-by-step design works because the sequence reproduces the way most city blocks were naturally created in the first place! Always try to reproduce temporal order in your design.

Here are examples of this design process applied to real sites in New England:

Project 1: Tracy Causer Block, Portland, Maine.

On what was formerly a surface parking lot, on a one-story sloping hill block, and barely larger than a half-acre around three existing buildings not owned by the developer, we designed 82 residential units, 15,000 square feet of retail, 30,000 square feet of office, 72 parking spaces and four interior pedestrian streets (one-way for cars). We ended up with what might qualify as 5 new blocks.

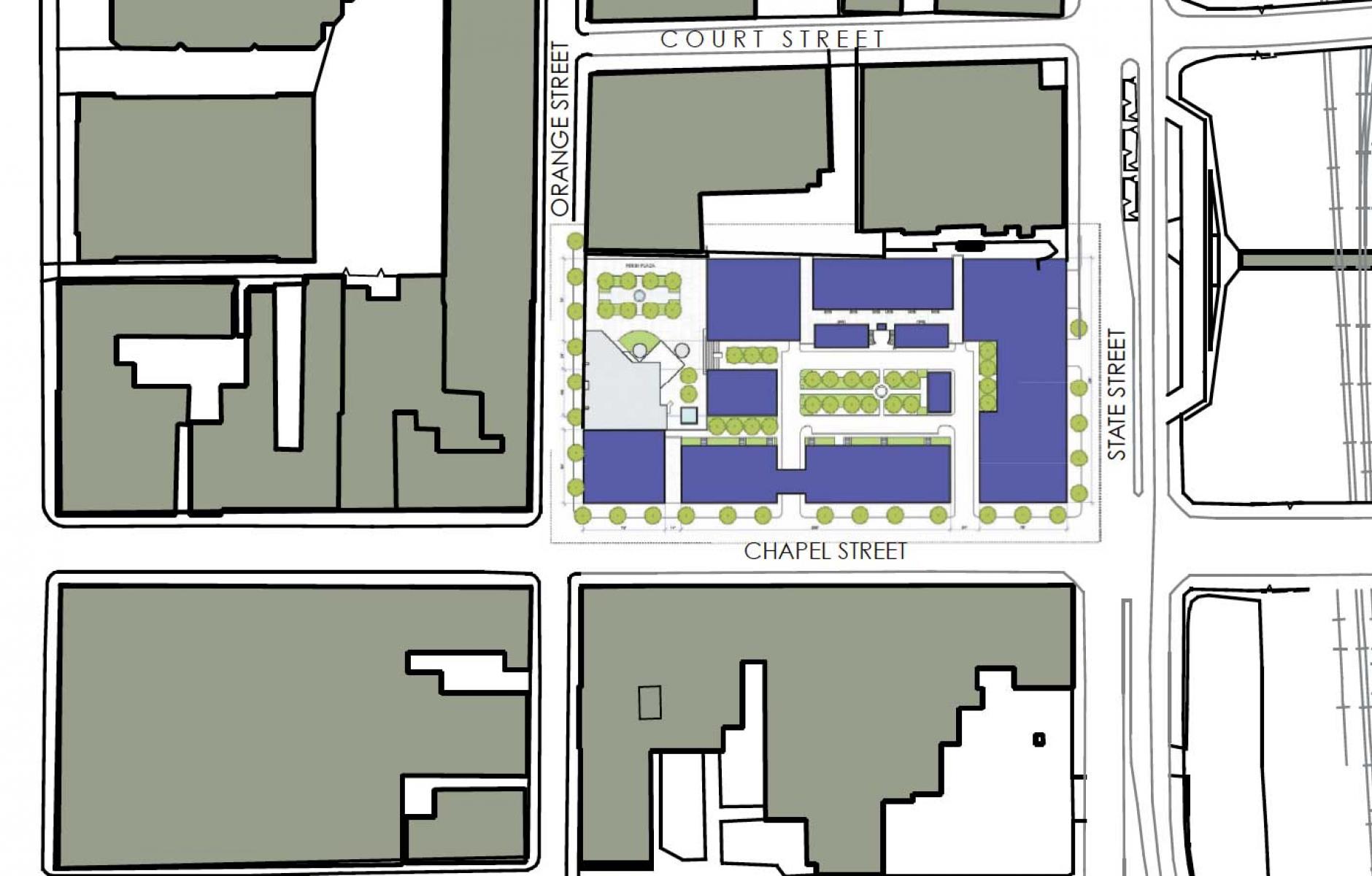

Project 2, Shartenberg Block, New Haven, Connecticut. (See plan at top of this article).

Located just one block from the historic Green, adjacent to the Ninth Square and across the street from the State Street train station, the 1.7-acre Shartenburg site has the potential to provide the critical mix of buildings and uses that will complement and knit together this portion of the city.