Dragon boundary markers

Historically, property boundaries were generally demarcated by a physical object, either by a boundary marker or a fence to visually communicate the edges of land ownership. These were human impositions that represented a cultural, political, and social meaning upon a natural environment or within a settled area.

In present day, the use of markers for land ownership has largely been replaced by maps and land-title registration. International borders continue to rely on markers which are traditionally classified into two categories: natural boundaries correlating to topographical features such as rivers, forests, or mountain ranges, and artificial boundaries unassociated with topography.

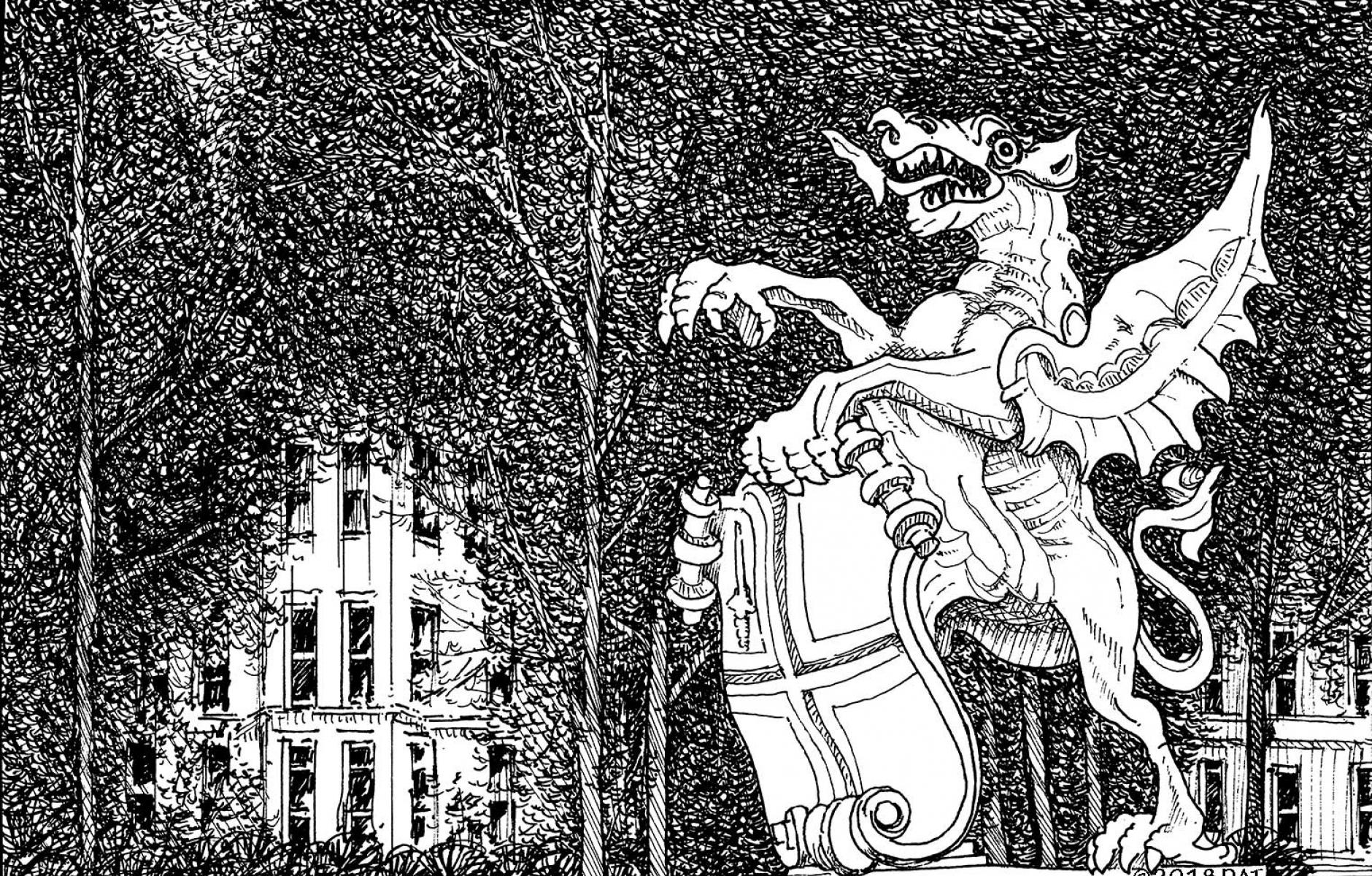

Cast-iron statues of dragons on plinths demarcate entry thresholds into the one-square mile City of London. Commonly referred to as The City, it constitutes the Roman settlement in the 1st century AD extended to the Middle Ages, and contains the historic center and primary central business district. Due to extensive growth, The City is today one of thirty-three local authority districts of Greater London.

The tall, black Temple Bar Dragon fiercely stands guard on Fleet Street overlooking the boundary between the City of London and the City of Westminster. It is the most celebrated gateway to The City and was the point where the Lord Mayor would welcome the ruling monarchy. Charles B. Birch designed the 14-foot-tall dragon in 1880.

The other Dragon Boundary Markers that guard the gateways into the City of London are painted silver with their tongues highlighted in red. The City of London shield, integrated into each sculpture, is painted white and red. The design is based on two seven-foot-tall dragon sculptures that were mounted above the entrance to the 1849 Coal Exchange. The building was demolished in 1962. The two statues were preserved, however, and re-erected on six-foot-high plinths at the western boundary of the City. These dragons were the model for the additional Dragon Boundary Markers installed at other entry points into The City.

The Celts believed in dragons and used its symbol to portray strength and power. In mythical legends, dragons were associated with protection and defense—and in medieval romance stories they guarded captive women. Pertinent in England, the use of the dragon in the City of London coat of arms was probably influenced by the legend of Saint George, who slays the dragon and rescues the princess chosen as the next offering for human sacrifice.

Unfortunately, these well-intentioned dragons at the thresholds of the City of London have been unable to guard against the onslaught of hubristic architects and developers. Falsely proclaiming sustainability, their profit-driven, out-of-scale glass towers are destroying the historic character of this once beautiful City.

The outcome of the recent building boom in The City is discordance at every level. The cacophony of buildings rising to the east of St. Paul’s Cathedral leaves much to be desired, especially at the pedestrian level. The argument thrust upon insecure decision makers — that an iconic glass tower skyline is necessary for a city to be taken seriously as a financial center — is utter nonsense. One can only hope that this lesson from London will convince other cities that the emperors of glass towers have no clothes.