A unified small developer vision for urban revival

As Flint, Michigan, declined from an industrial city of nearly 200,000 people to less than 100,000 people in 60 years, abandoned homes and blight became a big problem. Also, trust in the public sector and institutions declined, a situation that worsened in light of Flint’s notorious recent lead-in-the-water problem. Unemployment and crime are relatively high.

Kettering University, a small but prestigious science and engineering school and anchor of the local economy, had two choices: Build a virtual wall around the institution or engage the community in an inclusive, positive manner.

Kettering has chosen the latter, achieving a rising level of trust and community participation in recent years. The compelling news pertaining to Kettering and Flint—and other cities facing similar struggles—is the incremental and holistic path that the university chose toward community revitalization.

The university and its collaborators worked with the Incremental Development Alliance (IncDev) to explore how the area could look, which kinds of housing and mixed-use could be built, and where special attention could create community centers and amenities. The result is a new urbanist vision on a neighborhood scale geared to redevelopment by many hands. The large number of vacant lots in the area—a “hole in the donut” between the Carriage Town, Glendale Hills, and Mott Park neighborhoods—make the holistic vision possible. Yet the area is likely to come back through many small projects, rather than one big one. The University Avenue Corridor plan offers a unified small developer vision. I haven’t seen another plan quite like it.

The University Avenue corridor, and the donut hole that has been dubbed Durant Tuuri Mott, is depopulated to the point that very few houses are left standing on nearby blocks. Yet the corridor has four job centers within walking distance—or a short bike ride away.

A little more than a mile long, the corridor connects Kettering University with the Flint campus of the University of Michigan. The Hurley Medical Center, a sizable hospital, is just two blocks north. Downtown Flint is adjacent, to the southeast of the corridor. Although the city continues to lose population, downtown has already experienced a good deal of investment. “If anyplace in Flint will start to improve, this is the area, because there are assets,” says Thomas Wyatt, director of neighborhood and community services at Kettering University.

Parts of the avenue have benefited from street improvements, including a landscaped, tree-lined median installed in a center turn lane. The median slows down traffic, makes crossing easier where there are crosswalks and pedestrian refuges, and generally gives the thoroughfare a recently cared-for look.

The area suffered from crime hotspots and blight. A coalition was formed, now involving more than 80 stakeholder organizations, to identify short-term and long-term strategies, according to Jack Stock, director of the external relations for the university. The strategies focused on blight elimination, crime reduction, and social cohesion (getting the community together with a sense of purpose). “We had a lot of early successes with crime reduction and that got attention of the Department of Justice,” Stock says, and the DOJ provided the university with a million dollar grant to expand the program and hire a Wyatt, a full-time urban planner.

Wyatt attended an IncDev “boot camp” in 2015, and he brought the Alliance to Flint to do a workshop a year later, followed by an intensive design session and market study in the last two years. The charrette enumerated five key steps:

- Identify focus areas to concentrate small projects for maximum impact.

- Develop incremental strategies for focus area projects.

- Identify regulatory barriers to incremental development and incremental retail, and revise the land-use regulations accordingly.

- Identify a cohort of small developers and entrepreneurs.

- Identify lenders and grantors for small scale constructions loans.

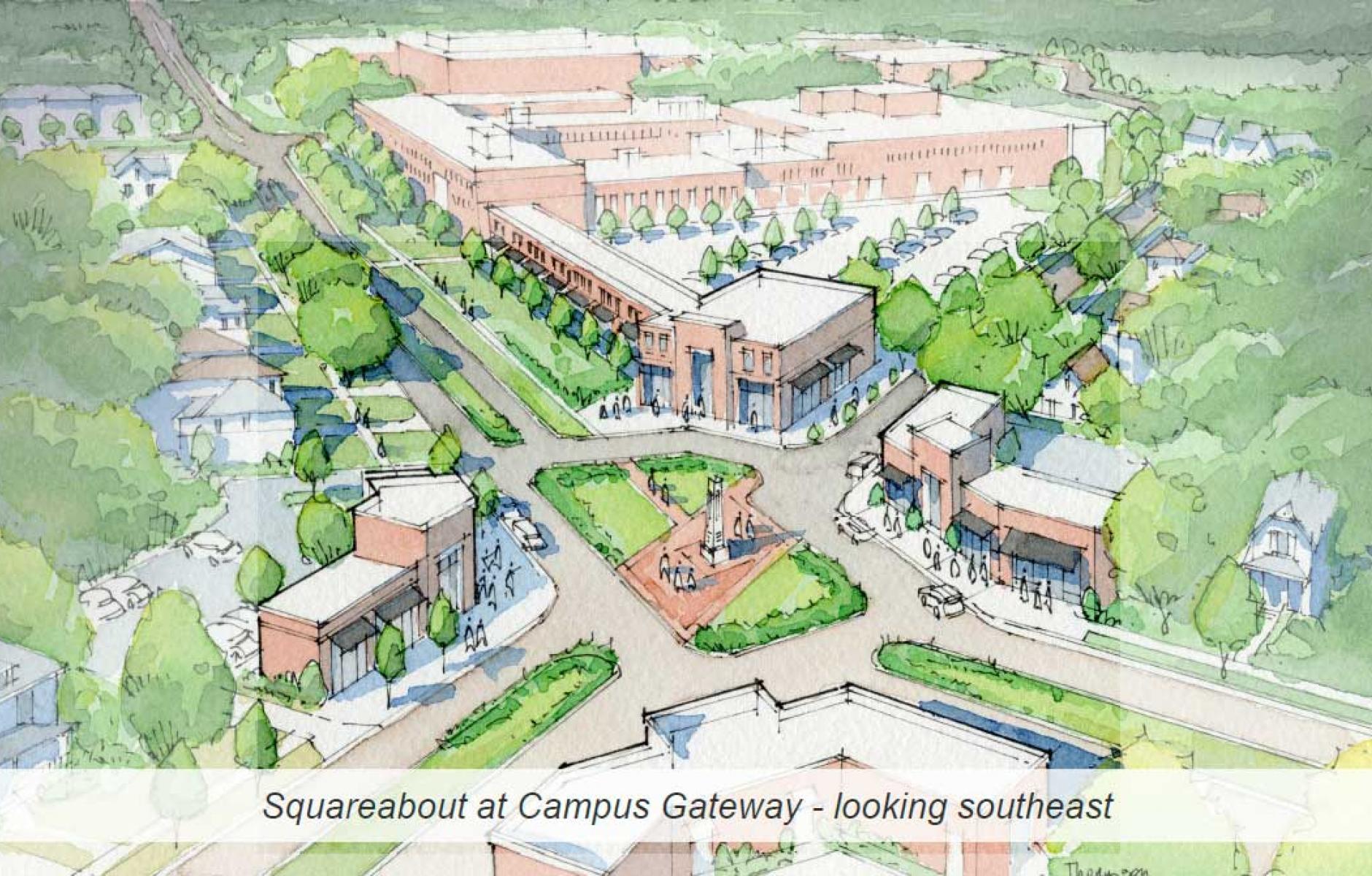

The charrette made significant progress with the first three items on the list, including identifying places and types for small-scale retail and a farmer’s market, missing middle infill housing, traffic-calming road improvements like a roundabout and “squareabout,” pocket parks, and a large civic space.

A typical idea of the charrette identifies blocks that are nearly empty as good locations for cohesive “cottage court” housing. “Cottages are generally smaller than typical single family yet still detached and with shared open space,” the authors note. “This housing type can also take the form of multiple side-by-side and/or stacked dwelling units arranged around a central shared open space creating a semi-private courtyard.”

Another charrette idea identified spaces for pop-up retail, food trucks, semi-permanent commercial buildings, and small stand-alone shops. “This range of commercial/retail options lower the barrier to entry for startup businesses while also allowing flexibility to upsize or downsize while also testing various locations. The old adage has been, ‘retail follows rooftops,’ but this concept allows both housing and retail/commercial to work together simultaneously avoiding the conundrum of which should come first.” Flint has historically lacked small neighborhood mixed-use buildings. The redevelopment of Durant Tuuri Mott offers an opportunity to introduce that kind of commercial development.

The plan includes many of the tools that could be applied in a neighborhood-scale plan with a master developer—although this plan lacks a master developer. The advantages of the "master developer vision" are conferred to the small developer cohort, who work independently but can see the bigger picture. They could choose to take part in any number of projects that would build value to the neighborhood as a whole—and that's a key goal of incremental development.

Since the charrette, the project has focused on the final steps—building the small developer cohort and figuring out how it can be financed—and then moving those developers into construction. “We're currently in discussions with some potential local and national funders,” says Wyatt. “We are also working through various Incremental Development Alliance activities that are occurring in other US cities and creating our own framework. More than 70 people participated in the small developer meet-ups that the 2018.” The goal is to get 12 small developers involved, including long-time residents, current home builders, investors, people who inherited property, and recent graduates and veterans.

Outside of the cohort, some residents are moving forward with their own property renovations. But the majority of the current work is by community development corporations and community development financial institutions. “The crux behind incremental development is one of values—find your farm and develop it,” says Wyatt. “We fully buy into it.”

Kettering specializes in hands-on learning—all students get extensive work experience before they graduate. Kettering is applying that hands-on approach close to home—rebuilding the neighborhood. The students and instructors, in this case, are members of the community. The next few years will tell the tale of whether this approach can revitalize a nearly abandoned part of a long-struggling city.