The great suburban Ponzi infrastructure experiment

Planner and engineer Charles Marohn has a knack for coining words and phrases that encapsulate big problems in the built environment. One is “stroad,” a thoroughfare that combines the characteristics of roads and streets and serves neither purpose well. Others include “the great suburban experiment” to describe how the US changed, all at once in the mid-20th Century, from proven traditional neighborhoods to untested sprawl; and “the growth Ponzi scheme,” which makes the case that unsustainable growth is propped up by more unsustainable growth.

My current favorite is the “infrastructure cult,” which captures the religious-like faith of US leaders and opinion makers in big public works projects—especially highways.

As founder of the nonprofit Strong Towns in 2008, Marohn advocates for community resilience through speaking engagements and the organization’s website—and now he pours his philosophy into a book: Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity.

The Strong Towns worldview is fairly closely aligned with New Urbanism. Marohn doesn’t mention New Urbanism in Strong Towns, but the acknowledgements reveal that his highest-level influences are new urbanists. Still, Marohn has founded a movement that is very much its own thing—I would venture to guess that most Strong Towns members do not identify as new urbanists.

Much of this book springs from Marohn’s personal journey, one that led him to a career attacking the cherished beliefs of his own profession and the long-time policies of municipal clients (this pathway may sound familiar to new urbanists). It started when Marohn analyzed return-on-investment for three infrastructure scenarios for the northern Minnesota City of Pequot Lakes. Marohn’s initial thinking, and that of the city engineer’s, was to support the biggest infrastructure investment—to “go big or go home”—and to assume that strategy would profit the city in the long run. When Marohn ran the numbers, they supported the opposite conclusion. “I had set up the study asking a question I assumed I knew the answer to, yet had never seen calculated by any engineer, planner, or economic development advisor before. It was disorienting to look at the data this way.”

He dove into more research, calculating how long it would take municipalities to pay back, with tax revenues, infrastructure projects that he was familiar with. What he found shocked him. “I subsequently modeled dozens of residential developments—urban, suburban, exurban, and rural—and I could not find one that came close to covering their own basic expenses, let alone the collector roads, traffic signals, bridges, interchanges, and other communal expenses those revenue streams were expected to support. Not one.”

This led him to the conclusion that modern municipal growth is a Ponzi scheme of sorts, which is one of the foundational ideas of Strong Towns, the organization. “New growth provides local governments an opportunity to receive additional cash in the short term in exchange for taking on unpayable, long-term liabilities,” he writes.

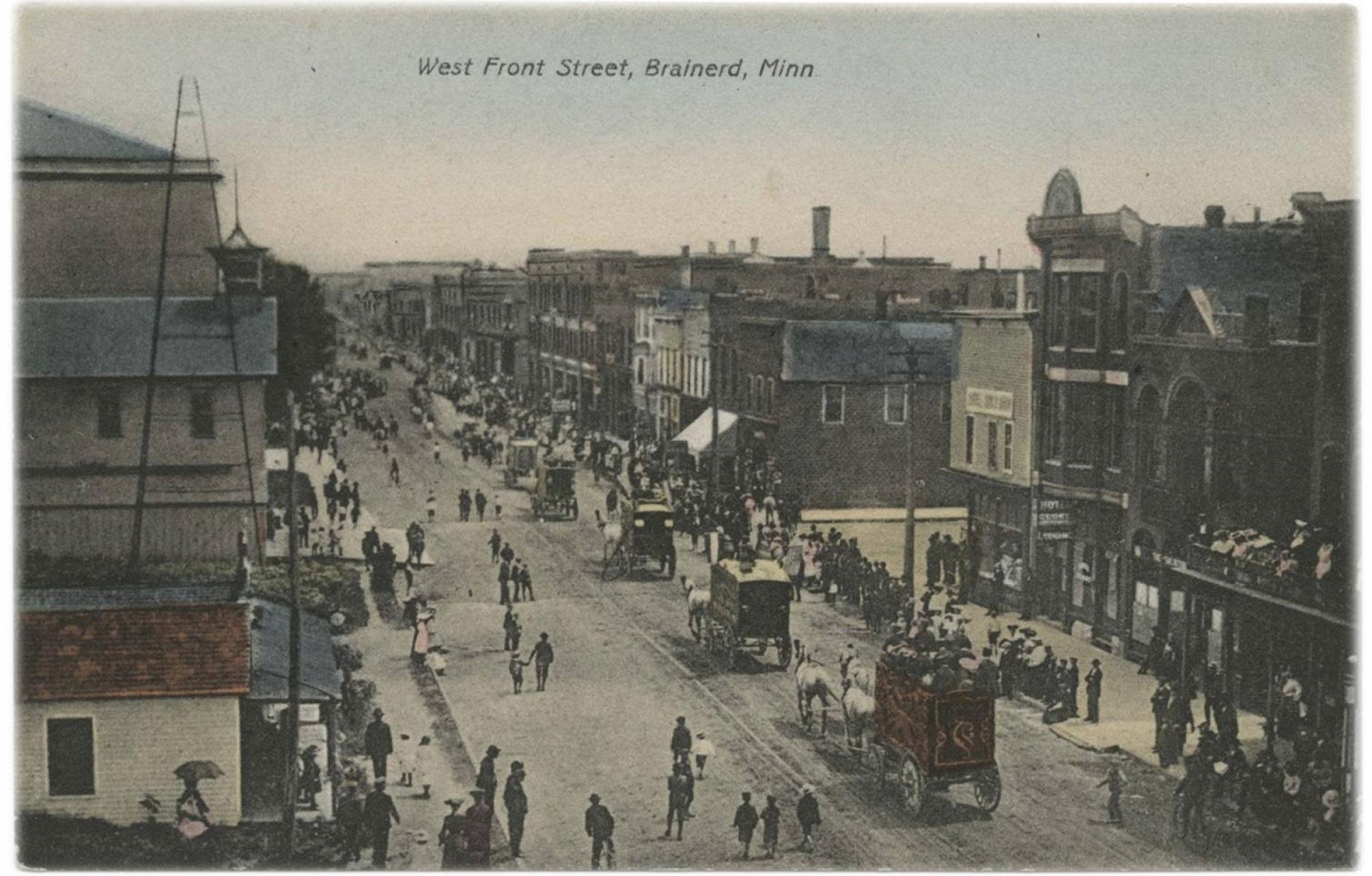

Along the way, Marohn learned from his hometown of Brainerd, also in northern Minnesota. He studied historical records and photos—detailed in the book—on how Brainerd grew incrementally from a frontier town of shacks after the Civil War to a thriving city with a downtown of masonry buildings in the 1920s. The downtown was built without modern finance mechanisms, zoning, state and federal infrastructure programs, civil engineering consultants, and everything that is thought to be absolutely necessary for city building today.

I’m reminded of lines from The Grinch Who Stole Christmas:

And the Grinch, with his grinch feet ice-cold in the snow,

Stood puzzling and puzzling. “How could it be so?

It came without ribbons! It came without tags!

It came without packages, boxes, or bags!”

Marohn compared the historic photos to the Brainerd of today, when many of the best downtown buildings had been knocked down for parking lots, the streets were widened, and the whole town was surrounded by sprawl. This current city grew out of the best practices he’d learned in school.

He puzzled and puzzled till his puzzler was sore.

Then the Grinch thought of something he hadn't before.

Charles Marohn bears no resemblance to the Grinch, yet I picture him standing in the late December snow of downtown Brainerd, floppy cap on his head, realizing that everything that he does for a living is not what makes a city thrive.

I am taking narrative license here, yet the lesson is real. And it can be extrapolated to every city in the US, which brings us to the “great suburban experiment.” Unlike good scientific experiments, which begin at a small scale and are carefully geared up—with controls to accurately test outcomes—this experiment was implemented at a stunning speed, at a stunning scale, in every US city, from Levittown outside New York City to a small town in northern Minnesota and everywhere in between.

“We started with an approach to city-building based on thousands of years of trial and error experimentation, a method that—while not necessarily efficient in its day-to-day operation—was stable, adaptable, and resilient. We now have a new, experimental approach, one where we make transformative investments based on our cultural desires, wrapping them in a veneer of intellectual theory and propaganda math,” he says.

Infrastructure cult

Some of the strongest arguments in Strong Towns relate to how the US spends federal and state infrastructure dollars. This is a rare issue that both parties tend to agree on, backed up by economists and talking heads of all political stripes, and Marohn makes a case that the system is completely bonkers.

“The American Society of Civil Engineers suggests that the federal government, on behalf of the American people, spend $2.2 trillion over a decade to save those same Americans from the hardship of having distressed infrastructure, a difficulty estimated to cost just $1 trillion,” says Marohn.

On closer examination, ridiculous math shifts to outright offensiveness, he says. “while infrastructure spending is done with real taxpayer dollars, the costs Americans would supposedly be saving themselves from are anything but hard currency.” The engineers are counting, in that $1 trillion cost, dubious figures such as time lost to congestion. “it’s not credible to suggest that saved time it going to result in increased worker productivity, let alone create real dollars that can be recaptured to pay for the project,” he writes.

The math is merely assembled as propaganda, Marohn says. “Building a highway? Calculate the time commuters save in transit but ignore the delays they have during construction and maintenance. Putting in a traffic signal? Calculate the value of potential new business growth but ignore the cost of time delays for people to sit at red lights.”

The latest fad, he says, is to tout a project’s carbon reduction benefits by calculating the potential to cut stop and go traffic, while ignoring the “the more obvious and intuitive fact that making it easier to drive means more people will drive, and more driving means more carbon, not less.” The issue is subject to confirmation bias—those who benefit from infrastructure seek only the facts that bolster their case—but the problem goes deeper. “It’s a foundational belief that’s not open to serious examination.”

When a major public works program is promoted, the emphasis is often on jobs. Yet we might be better off digging a ditch and filling it back in again, Marohn suggests. “With the ditch, we ultimately end up back where we started. There’s no long-term liability. In contrast, when we build a road or a bridge or a mile of pipe, we’re left with an eternal maintenance obligation.”

A focus on wealth

The belief in building highways and other massive infrastructure projects is related to the reality that, since World War II, our economy has become dependent on growth, he explains.

“The economics of a traditional city was like a person standing. It could grow, even very rapidly, but it was also stable without growth. Growth was a positive condition, but not a requirement. In contrast, the post-Depression American city is increasingly like a person on a bicycle; it must keep growing, at ever accelerating rates, or things fall apart.”

Rather than growth, local governments seeking to create successful human habitat could shift their focus to “wealth creation,” Marohn says. Traditional, compact, mixed-use neighborhoods on street grids have been shown to create wealth.

These kinds of neighborhoods are able to constantly evolve—that is, if they are not hampered by overly restrictive zoning. “Zoning codes established for the rapid replication of the auto-oriented development pattern were also applied to urban neighborhoods,” he writes. “These codes do not allow neighborhood evolution; their central feature is to ‘protect’ existing property owners by locking the current development pattern in place.”

When values go up, overly regulated neighborhoods cannot change—unless a developer has enough capital to fight for a zoning change or go through years of entitlement. Currently our codes promote “random shifts in intensity instead of smoother increments of change,” he says.

The solution is that “The next increment of development must be allowed by right, but no more.” That’s a good idea, and it is easier said than done. One shortcoming of Strong Towns is that Marohn does not explain how the “next increment” is determined. To be fair, this is an evolving issue. Some answers may be found in CNU’s Project for Code Reform.

In general, Marohn says, empty spaces need starter homes and buildings should be allowed to evolve over time. “Single family homes must be allowed to add accessory apartments, or convert to a duplex, without special permitting, approval from neighbors, or added conditions.” To become more financially productive, we need our neighborhoods to “thicken up,” Marohn says.

To retrofit or not

I disagree with some of the conclusions in the book. One has to do with “suburban retrofit,” the term used to describe reuse of shopping malls and other suburban places to introduce more sustainable development patterns—often mixed-use urban centers.

“I have serious doubts about the capacity of Americans to experience Suburban Retrofit as anything more than a niche undertaking in the most affluent places,” he says. “The cost of these projects is enormous, far beyond what makes sense for most places.”

On the other hand, Marohn touts a value-per-acre measure as a test of high financial productivity. Once built out, mixed-use centers in the suburbs have high value per acre. If well designed, they also meet other heuristic tests that correlate with wealth creation—connected networks of streets and a high-quality public realm.

I agree with Marohn’s use of the word “niche” to describe suburban retrofit, because the concept is being tested out on a relatively small scale relative to the vast scale of the suburbs. Unless we decide to completely give up on the suburbs, which comprise at least 90 percent of American metropolitan areas, it seems wise to test new development patterns and see what can reasonably be improved (maybe more than Marohn imagines). Strong Towns presents no financial analysis of specific suburban retrofit projects—yet Marohn is dismissive of the concept. “Many technical professionals who advise cities, along with many developers well versed on both subsidies and municipal desperation, are smitten by the concept of Suburban Retrofit. It allows them to pretend that their bold visions can lead the way out of the decline we're trapped in.”

That sounds far too sweeping. He may be right—on the whole. That doesn't mean suburban decline is inevitable everywhere, or that we can do nothing within the constraints of good policy and sound fiscal judgment to make the suburbs a lot better.

Notwithstanding such concerns, Strong Towns makes a strong case for a more rational view of development and infrastructure, from federal highway policy down to a single stretch of sidewalk. The best investments in the built environment are maintenance of neighborhoods that have stood the test of time, he says. “See a streetlight out, replace it. See a weed: pull it. See a crosswalk faded: repaint it. See a sidewalk broken: Fix it. The neighborhoods that are generating such wealth for the community need to be showered with love.”

Such maintenance is a wise financial investment, and also gives residents the confidence to invest their own properties. Marohn is a strong proponent of incremental development. As he puts it: “Start with a pop-up shack and eventually get to Manhattan.”

Well, not usually Manhattan. Maybe it’s a main street that lasts two hundred years. Or a mixed-use walkable neighborhood where children are empowered to walk to school.

Most importantly, he says, build neighborhoods one small step at a time rather than going straight to utopia. “The key difference between historic development patterns and the way Americans began to build cities in the twentieth century is our capacity to skip the messy iterations and jump to what we perceive to be the perfect end.”