Former airport turns into complete community

When the first Charter Awards were announced in 2001, the Mueller Airport Reuse Plan in Austin, Texas, was among the 15 outstanding projects selected. The first shovel would hit the ground nearly a half decade later, and now the jury can take note of the community magic achieved nearly 20 years later.

“One of my favorite past times when I sit on the porch is to count the different mobility modes people are using and it never fails that there are more pedestrians than drivers,” says Veronica Castro de Barrera, an architect who has lived and raised a family in Mueller (pronounced “Miller”) since 2009. “That makes me extremely happy to witness the evolution of a walkable neighborhood into a truly actively mobile place for all ages and abilities.”

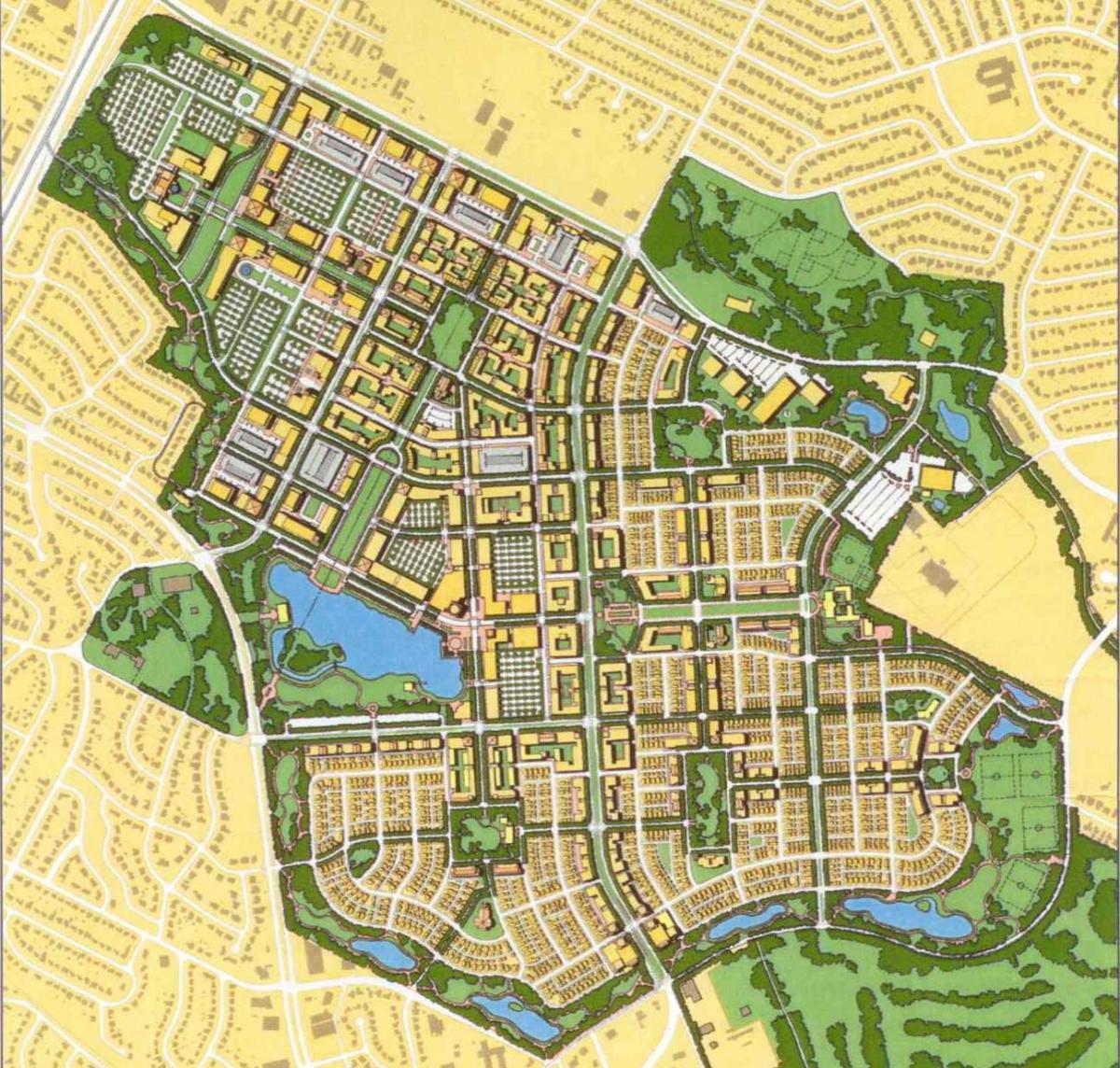

Her home is one of more than 4,000 diverse living spaces built so far on the 711-acre former airport. Mueller has become a major employment center, and the town center is a lively place—rapidly expanding with new construction. Mueller’s parks attract visitors from across the city. About 35 percent of the living units meet affordability standards, the result of a public-private partnership. The market response to the project has been outstanding, and the units that are not affordable have become very expensive.

Mueller has struck major turbulence along the way and the flight path has changed many times. The project would never have taken off at all if not for unique circumstances that allowed for a hole in the urban fabric to be filled with development that looked unlike anything Austin had seen in more than a half century.

“Austin has been at forefront of sustainable design and green building,” says Jim Adams, who was principal at ROMA Design Group, which drew the Charter-winning plan. Now with McCann Adams Studio, Adams lives in Mueller and has effectively served as town architect throughout the project. Austin was one of the first cities in the US to adopt a traditional neighborhood development (TND) ordinance, the forerunner of a form-based code, in 1997. Austin’s ordinance served as a model for other cities at the time. Starting in 1997, when ROMA was hired, the city saw Mueller as an opportunity to create a laboratory for TND and green building and change the pattern of sprawl that had long dominated development. The city sought sustainability, and affordable housing, and a project that would stand on its own financially. There would be no compromise on those three goals.

That approach was nearly unique at the time, Adams says, yet Mueller would never have been built in its current form if not for an unusual neighborhood process that took place in the mid-1990s.

“The surrounding neighborhoods formed a task force that promoted a responsible approach to redeveloping the airport,” he says. “They created a vision that was very rudimentary and mixed-use. During the master planning process, the neighborhoods were very involved. Without that support, even with the progressive approach of the city, it would never have happened.”

The neighbors were largely Latino and African-American. East Austin was the part of the city reserved for minority populations during segregation. Economic development was a priority, yet many believed that such development would not be financially successful in East Austin, Adams says.

The plan was delayed for a few years because the state owned some of the land and had no interest in New Urbanism. After ownership was resolved and city adopted the plan, a developer had to be found. Catellus, based in San Francisco and Denver, was selected. Then the plan had to be revised and the developer agreement signed with the city, which took until 2004. Infrastructure construction began in 2005, and the first houses came out of the ground in 2007.

Surviving the black swan

The timing could not have been worse. The Great Recession hit in 2008, and this killed thousands of real estate projects—including large projects with bad timing, like Mueller. The developer agreement, in which the city agreed to be patient in receiving its payments, helped to save the project—in addition to the resilience of the plan. “After a brief slow-down in construction after 2008, construction ramped and accelerated starting in 2012,” says Mateo Barnstone, a Mueller resident and director of the local CNU Chapter, CNU-CTX.

The plan evolved, and the block and street pattern allowed for flexible build-out. The current plan calls for 7,500 living spaces, substantially more than the original 4,500, plus about 5.5 million square feet of commercial, says Adams. “In terms of design, we established a resilient framework that allowed us to increase density almost two-fold without losing quality,” he says. “I think the density improved the quality of the place.” The town center became more compact and interesting, with structured parking and vertical mixed-use, while using the same block pattern and public spaces.

The increase in density has been prompted by the ultimate market success and the need to maintain the affordable housing program. Just over half of the development program has been built, and 80 percent of the infrastructure. Most of the remaining housing will be multifamily, with one single-family neighborhood still to be built. Mueller has about five years to completion, Adams says.

A high bar for affordability

The agreement with Catellus called for 25 percent of the units to be affordable at 80 percent of Area Median Income (AMI), with rental units at 60 percent of AMI, and some units have been as low as 30 percent. That’s a tough standard to meet, especially since market prices soared. The developer agreed to provide an additional 10 percent of housing at between 80 percent and 120 percent of AMI to meet a gap in workforce housing.

“The challenge as house prices continue to appreciate more and more, it is difficult to sustain the affordable housing program,” says Adams. “We have come up with newer building types that we did not envision back in 2004.” One recent example is a 675 square foot lot—a fee-simple townhouse facing a paseo at 27 units to the acre.

At the same time, the economic success of Mueller has allowed the developer to put some of the profits back into meeting the original community goals. Ultimately, Mueller may provide close to 2,500 units that meet affordability standards for East Austin, a part of the city that has experienced substantial gentrification. “I believe the higher density has been a very positive move as we now have more townhomes and apartments including a higher number of housing units in the affordable program,” says Castro de Barrera.

Building a complete community

One of the earliest implementation successes was the inclusion of the Dell Children's Medical Center of Central Texas as the first institutional anchor, says Greg Kiloh, an urban planner and a former economic development project manager for the city. The medical center has since been joined by an impressive list of institutional employers: University of Texas Pediatric Research Center, Austin Independent School District Performing Arts Center, Thinkery Children's Museum and neighboring Austin Film Studios, Central Texas Emergency Command Center, Robert Rodriguez' Troublemaker Studio and Rathgeber Village non-profit campus. The Texas Mutual Insurance Company moved their 250,000 square foot headquarters to Mueller. Mueller will eventually have 15,000 jobs—about the same as the total number of residents.

The employers join other occupants of the town center, which is now rapidly developing. “When we first moved to Mueller, there were no businesses established yet, but now we have beautiful cafes, restaurants, a farmer’s market, movie theater, wonderful grocery store, and shops,” says Castro de Barrera.

A full range of missing-middle housing types complement the mixed-use, says Barnstone. They include: Single family yard homes, narrow lot urban homes, garden court homes, row homes, garden court row homes, duplexes, small multi-plex 4- and 6-unit homes known locally as “Mueller Houses,” shopfront homes, and mixed-use multi-family.

The physical diversity and design contributes to a strong sense of community. “We have lived here long enough to have made deep connections with our neighbors that we truly consider them an extended family,” says Castro de Barrera. “We have celebrated births and mourned deaths and helped families deal with difficult illnesses. I am very blessed to have raised my children in this environment and I hope that by giving my children a ‘free-range childhood’ will influence how they want to live as adults and how they want to raise their families in the future.”

Focus on the public realm

Mueller places high emphasis on the design of streets and parks, the planting of trees, and the overall walkability of the public realm. This adds up to the most visible difference between this development and everything around it.

“The parks are really incredible and attract people from all over the city,” says Barnstone. “They’re spread throughout the project such that no one is more than a few minute walk from one or several parks.” These include: Greenways, long linear parks that offer a way to get around free from traffic; Neighborhood Parks with pools, playgrounds, fields, sports courts, and community gardens; Pocket Parks that are gathering spots for neighbors; and the Lake Park, a 30-acre park adjacent to the town center.

These public spaces were part of what impressed the jury in 2001. “This is a great example of a new neighborhood that is integrated into its surroundings,” said architect and former Charlotte Mayor Harvey Gantt. “The new area will share open space and boulevards with adjacent suburban developments.”

Many of the streets, as built, are relatively narrow and tree-lined—and some are wider than need be. The buildings are close together, with no garages to mar the streetscape. “Our street is always full of life with pedestrians, cyclists, parents pushing strollers ... every kind of wheel (and every kind of pet) you can think of passes in front of our house,” says Castro de Barrera.

Building walkable streets has been an ongoing challenge. Early streets were quite narrow, but then the Austin Fire Department, under new leadership, opposed those cross-sections as unsafe for emergency vehicles. “While the result wasn’t as terrible as it could have been,” Barnstone says, “it did mean making certain compromises on some streets—pulling back parking from corners, or off of one side of the street in some cases, to allow the width the fire department now requires for their emergency vehicles.”

Every silver lining …

A project this ambitious can’t avoid all compromises and unintended consequences. The project includes a typical-looking power center with Home Depot, Marshall’s, Old Navy, PetSmart, and other chain stores. The area was necessary to put Mueller on a solid financial footing early on. It was designed with the parking lots on a block-and-street network, so that the area can be redeveloped later as mixed-use. “We believe that this area will get redeveloped in ten to fifteen years,” Adams says. “This hasn’t really affected urban character of Mueller, since it is on the edge. We have retail uses that hug the street.”

Although Mueller has great street trees, many of them are maintained by the owners of the homes fronting the street, which means that some are dying for lack of care. Having the Property Owners Association, which does an excellent job with the parks, maintain the street trees would have been a better choice, Adams says.

Maybe the greatest disappointment of Mueller stems from its success. Aside from the third of properties that are affordable by agreement, the project has some of the highest real estate prices in Texas. This may not be surprising, given that Austin is one of the fastest-growing cities in the nation (22 percent population growth this decade so far). Mueller offers high quality of life in a prime location just a few miles from downtown. Mueller is one factor among many in the gentrification of East Austin. The development’s demographics are diverse—reflecting the city as a whole, but not that of East Austin 15 years ago. Judging by the support for amendments to allow more density over the years and up to the present, it retains support among neighbors.

Mueller’s impact on other large communities has been less than one would hope. “The primary success is that it has demonstrated that a new urbanist approach to development is viable in Austin,” Kiloh notes. “Unfortunately, it has not spawned as many imitators as I would like to see. The project is wildly popular as a real estate development. It has been seen as a laboratory for new urban design ideas, and has implemented a number of them over the years.”

Mueller has achieved its goal of spurring new investment in a part of the city that needed revitalization, as indicated by 2001 Charter Award commentary. “The project is intended to be a catalyst for economic renewal throughout the area,” CNU wrote. “Successful redevelopment of this significant property in the deteriorated eastern part of Austin offers an opportunity to encourage new investment in the existing neighborhoods, creating a community that will enhance the quality of life and the identity of the area and make it more attractive for ongoing investment and revitalization.”