Authenticity by design: Creating beautiful places

Note: This article is based on a presentation by Daniel Morales at CNU 28.A Virtual Gathering, which took place in mid-June.

What makes a place lovable? At CNU 27 in Louisville (in 2019), someone said, “Lovable places were often created by many people over many different years, lending them authenticity.” This implies that we love older places more than new ones. But when was the last time you stood in a beautiful town square and thought about authenticity?

The traditional city is a pedestrian city, whose buildings where designed to work together. When good urbanism was the norm, it was the architecture that gave a place its unique character. The question then becomes, what is it about older places which make them lovable? They have what I call harmonious beauty. Historically, architects employed a language of compositional patterns that enable buildings of various styles to harmonize. People love these places because they are picturesque.

Rather than worrying about authenticity, we should focus on the quality of our designs. This means prioritizing beauty once again, as the medieval city of Siena did in their constitution of 1309, were it stated: “Whoever rules the city must have the beauty of the city as his upmost preoccupation to provide pride and honor to the citizens as well as pleasure and happiness to visitors from abroad.” Five Hundred years later, the planner Camillo Sitte reiterated the importance of beauty in public space. In his book, “City Planning According to Artistic Principles.” he echoed Sienna’s constitution, writing “Major plazas and thoroughfares should wear their Sunday best to be a pride and joy to their inhabitants.”

By the early 20th Century, the awareness of beauty’s importance in planning culminated in the City Beautiful movement. A more picturesque approach was employed in street car suburbs such as Forest Hills, a neo-medieval confection that still commands high rents because of its excellent design. Even though it was built-out at once, its picturesque massing and elegant detailing lend the illusion that it was built over time. As Camillo Sitte said, “whatever makes up the trappings of stage set architecture would be of no misfortune for a city.”

This changed with the advent of Modernism. After WW II, schools abandoned the study of composition and the use of historic precedent. The public realm became secondary as planners designed cities around the car and architects offered pedestrians a blank facade. By rejecting the lessons of traditional architecture and urbanism, architects lost the ability to design good pedestrian buildings.As a result, many of the places we build discourage walking and the social interactions that build real communities.

Today New Urbanists rely on form-based codes to ensure a level of harmony among different buildings. The problem arises when a project requires a large footprint. So how does one scale a building down to blend in with fabric of an historic town? By remembering what Shakespeare said, ‘All the world’s a stage,’ and by extension, buildings are the stage set.

A great street is like an orchestra where the buildings work in concert to create a visual symphony. Conversely, when designing a block long building, one should break it up into several facades to create a better pedestrian experience.Studies have shown that people react negatively to large buildings devoid of articulation, while others with too much variety result in cacophony. Having evolved to make sense of our environment, places that ignore our need for ordered complexity cut against the grain of our evolutionary impulses. A street can handle a few dull facades, but without an underlying pattern language to engage the passerby, the view becomes monotonous.

When well composed, the relationship between a detail to a building, a building to a street, and a street to a neighborhood creates a harmonious ensemble that results in a lovable place.

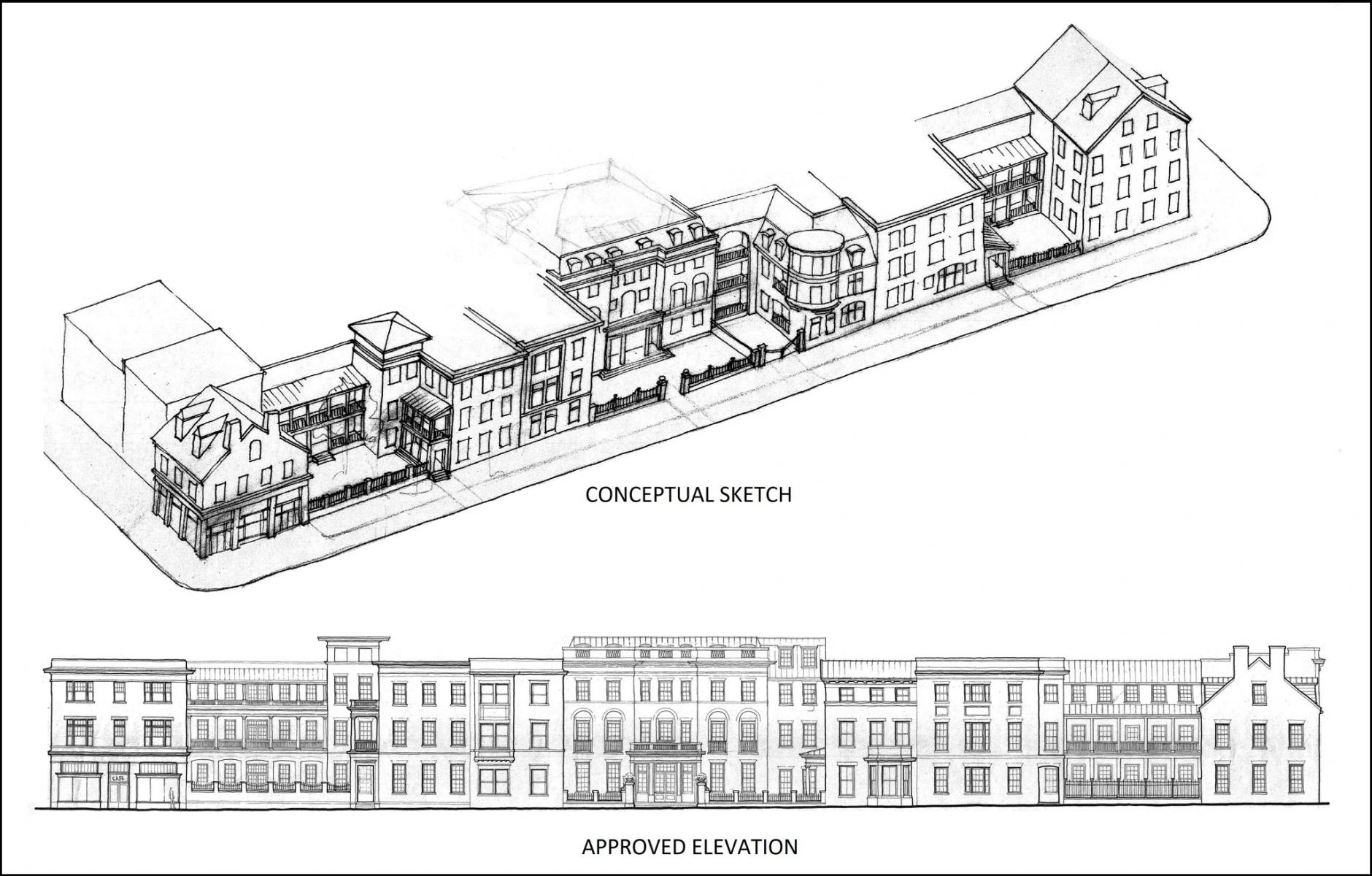

The following are two projects I worked on where we had to insert a block long apartment building into a finely grained neighborhood. In both cases the projects stalled out at the citizen’s review stage because residents felt they did not fit in.

The first is in Silver Spring, Maryland, where the developer proposed a large building that could have been built by right. Working with the residents, I offered them a density bonus in exchange for breaking up the street wall with facades of various heights and materials. The second project is in Alexandria, Virginia, a 300-year-old town and home of the first CNU. After several attempts, we finally got approval after breaking up the massing with a mix of facades drawn from the historic fabric (see image at top of article). Because the building’s height was fixed at three stories, we used courtyards, tower elements, and chimneys to enliven the skyline. In both projects, no resident ever mentioned the debates over style or authenticity that confound modern architects, they simply liked that the buildings fit in.

Today, there are still some who would argue that dressing up a large building to look like many is inauthentic, that it must truthfully express its function and size even if it results in a depressing environment. These people forget that the places we love have survived not just because they are useful or meaningful, but because they are attractive. As the National Trust for Historic Preservation put it, “the real value of any building lies in its being a delight to the eye and its susceptibility to human use.”

Beauty is not an intellectual concept, nor is it something that can be codified. It is a feeling one gets when things works well together. So, while there’s no guarantee that calling for beauty will produce a lovable place, it’s the effort that counts. Like when one goes to a home where the host has created an inviting setting, we might not share their taste, but we’re flattered that they sought to please us. This effort is why we love historic towns, because those who built them sought to please the beholder’s eye. As the father of Town Planning, Raymond Unwin said, “Beauty is an elusive quality, not easily defined or attained, and yet it is a necessary element in all good work.”