America needs civility, and civic art can help

Civic space and civic art can play a vital role in the stability of societies. We inherently desire beautiful places to inhabit and be inspired by. We also desire doing so in the company of others because we have the common goal of living in a good and just society. A successful civic realm can provide that context for a range of needs. In a physical context of positive togetherness that accommodates socializing, dialogue, and the celebration of beliefs—civility thrives. Recapturing this notion can help us to resolve the societal issues of distance and difference we are facing today.

Civility: formal politeness and courtesy in behavior or speech—Merriam Webster

With the passing of Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) in July, much has been said about his courage and legacy as a civil rights leader. The success of the civil rights movement is revealed in its achievements through leaders such as John Lewis and Martin Luther King, Jr.—two of the Big Six leaders. Their success, and that of the movement, was gained through the understanding that you cannot change someone’s mind through violence, coercion, and being separated. Instead, success was achieved by appealing to the humanity of others in bringing them closer to witness inhumane treatment and thereby illuminate the human dignity of black people.

Implicit in the civil rights movement was also a spirit of forgiveness and reconciliation enabling both sides to come to terms with past—and present—wrongs. Outside of America, we can also see a good example of civil reconciliation in South Africa after Apartheid. The “Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” lead by Nelson Mandela, held open hearings to provide a venue for those on both sides to share experiences and voice contrition. Today, one might be hard pressed to recognize this same type of civil leadership in our country. And, while there are peaceful non-violent protests, activists have hijacked these efforts for causes that go beyond racial justice and in a manner that espouses chaos and not civility.

Distance and difference could be identified as primary factors in how we have failed to correct our country’s past wrongs. During slavery, while slaves and masters were literally proximate, the belief that slaves were less than human, and thereby different, cast the largest chasm possible between human beings. Following that, and adding to it, in the Jim Crow era, while black people were free, everyone was put at a distance through segregation, exacerbating feelings of prejudice. Conversely, civil rights leaders promoted proximity and commonality through inclusive engagement in paving the way for compassion.

It is arguable that we have not meaningfully picked up the mantle of civil rights since that era and today are witnessing the effects of that abandonment with an ever widening gap of distance and difference. Adding to that gap is a broader dynamic of suburban sprawl, gentrification, virtual immunity, personal autonomy, and isolationism. Within such a context real and mature engagement is difficult to come by, such that feelings of selfishness, indifference, entitlement, and unabated offense (whether real or imagined) are allowed to prevail. This perhaps begins to explain the disturbing trend of civic iconoclasm, the sudden need to destroy things that are deemed “threatening.” Attacks on statues of historic, patriotic and cultural heroes, religious figures, and churches suggest that nothing is immune to these violent uncivilized acts of “purification” in the removal of civic art from the civic realm.

This then leads to the question, should we have civic art at all, or should we aim to avoid any potential offense whatsoever? At the end of the day is there anyone or anything that is immaculate enough to withstand all scrutiny? What is the purpose of civic art anyway—is it just a collection of inanimate attractive or provocative objects with no real use? To answer this question we need to consider the essence of civic art and its value. The purpose of civic art is not merely functional but goes beyond, to fulfill a ritual need that human beings have projected from the beginning of time. A need to transcend the mundane. It is not particularly rational in a worldly sense—but can be likened to our need for love. Love is useless, as is art, when constrained by utilitarian concepts of necessity. Instead these things are more like gifts that have the ability to fulfill human needs through arresting our attention and adoration, ideally inspiring us as constant reminders to transcend our own condition to be better and to mature for ourselves and our society. Civic art, while produced by flawed creators and therefore subject to being flawed itself, offers value that we don’t want to throw out with the bathwater. Civic sterilization on the other hand, while it may be pragmatic, is inhuman and draconian.

If we acknowledge the value of civic art, we should consider that civic art, like human beings, should be held accountable and be afforded the opportunity, where necessary, to “mature” in the context of civil engagement. What I would propose is that we double down on our investment in the civic realm and art by supporting its own maturation with the benefit of reciprocal reward.

To illustrate an instance where “maturation” could be employed, in an attempt to test the boundaries of civility and forgiveness, I have looked to the state of Virginia for some challenging subjects. Virginia has a disproportionate ratio of confederate memorials to those of African Americans of any kind, at about 23:1. To address the controversial nature of the memorials and make up for the disparity, without adopting a policy of nullification, existing sites can be contextualized, augmented, or co-opted. By including additional works in close proximity, with possible modification of existing pieces, sites can offer a much more rich, complete, and sophisticated interpretation of the historical events of the Civil War. This approach differs from the “memorial garden” concepts found in places like Lithuania and Hungary. Instead it would be a full-throated occupation of a primary civic space intent on taking center stage. I propose the following modification of two prominent confederate memorial sites for Lee and Davis on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia.

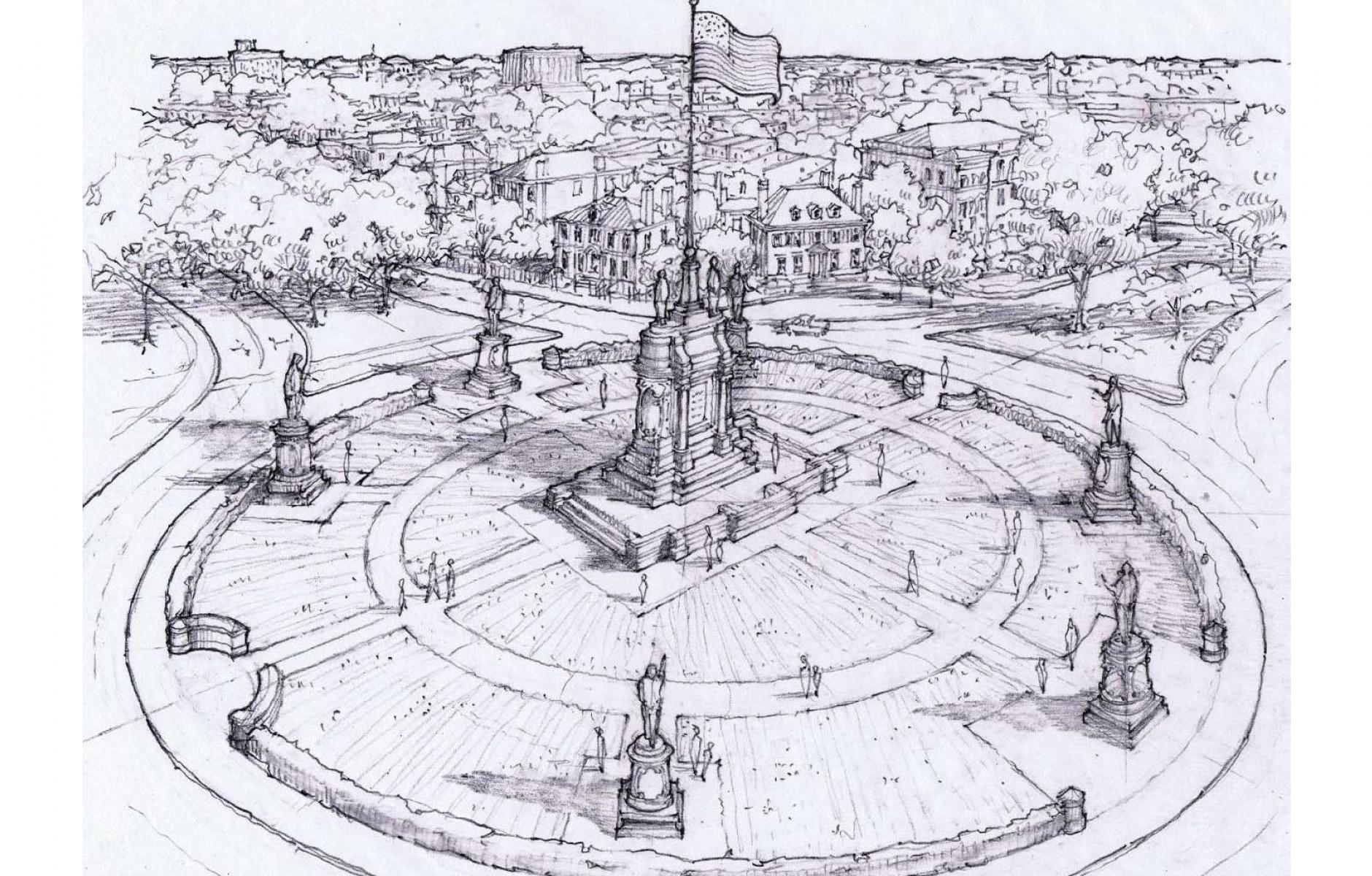

In addition, I have included a more specific proposal for the Robert E. Lee memorial circle, that more clearly reflects the civil concepts of proximity and commonality in a civic space. What is shown is essentially a frozen civic “Truth and Reconciliation Commission.” To achieve this, the site would undergo a transformation from the veneration of Robert E. Lee, who by all accounts did not want to be commemorated for losing, to a populated space full of figures from the Civil War, including Lee. The heroic equestrian statue would be taken down to be housed in a museum, while the existing pedestal becomes a co-opted generator of the aesthetic theme for the entire circle. No expense was spared in creating this sculptural work intended to inspire awe, elicit delight, and resonate with human beings—in its sophisticated deployment of the classical language. Ultimately, it is a very accomplished beautiful work of art well suited by means of decorum for the task of civic art. Finally, atop the pedestal would reside new allegorical figures of Justice and Peace and in the middle of the composition, an American flag symbol of unity.

The proposed scene acts as a model of civil confrontation in a civic context. Silent beings come together in implied reconciliation through proximity and commonality. Does augmenting this civic space eliminate and prevent all evils? No, but it does present a vehicle for resolution. Taking pride in a shared place to help overcome distance and difference through engagement, helps us to appreciate each other as human beings, flaws and all. It is also a poetic gesture of freedom of speech, in that we have the freedom to speak openly without retribution and the freedom to make mistakes without being dismissed from existence. America has complex and deep sins—but not insurmountable ones. In this way we also celebrate the overwhelming virtues our country has that make it possible to achieve peace with the past. The presence of civic art within our civic spaces can be powerful reminders of those goals in channeling the main ingredient of civility.