Great Senior Short Sale threatens housing market

A growing mismatch between America’s housing supply and changing demographics could trap millions of senior citizens in unwanted houses, according to a report by University of Arizona researcher Arthur C. Nelson.

The mismatch is brought on by an excess of large-lot single-family houses and a growing demand for walkable communities. Despite the desire of many senior citizens to age in place, they will eventually need to leave isolated single-family houses—and these houses will sell at fire-sale prices in many parts of the US, Nelson’s research concludes.

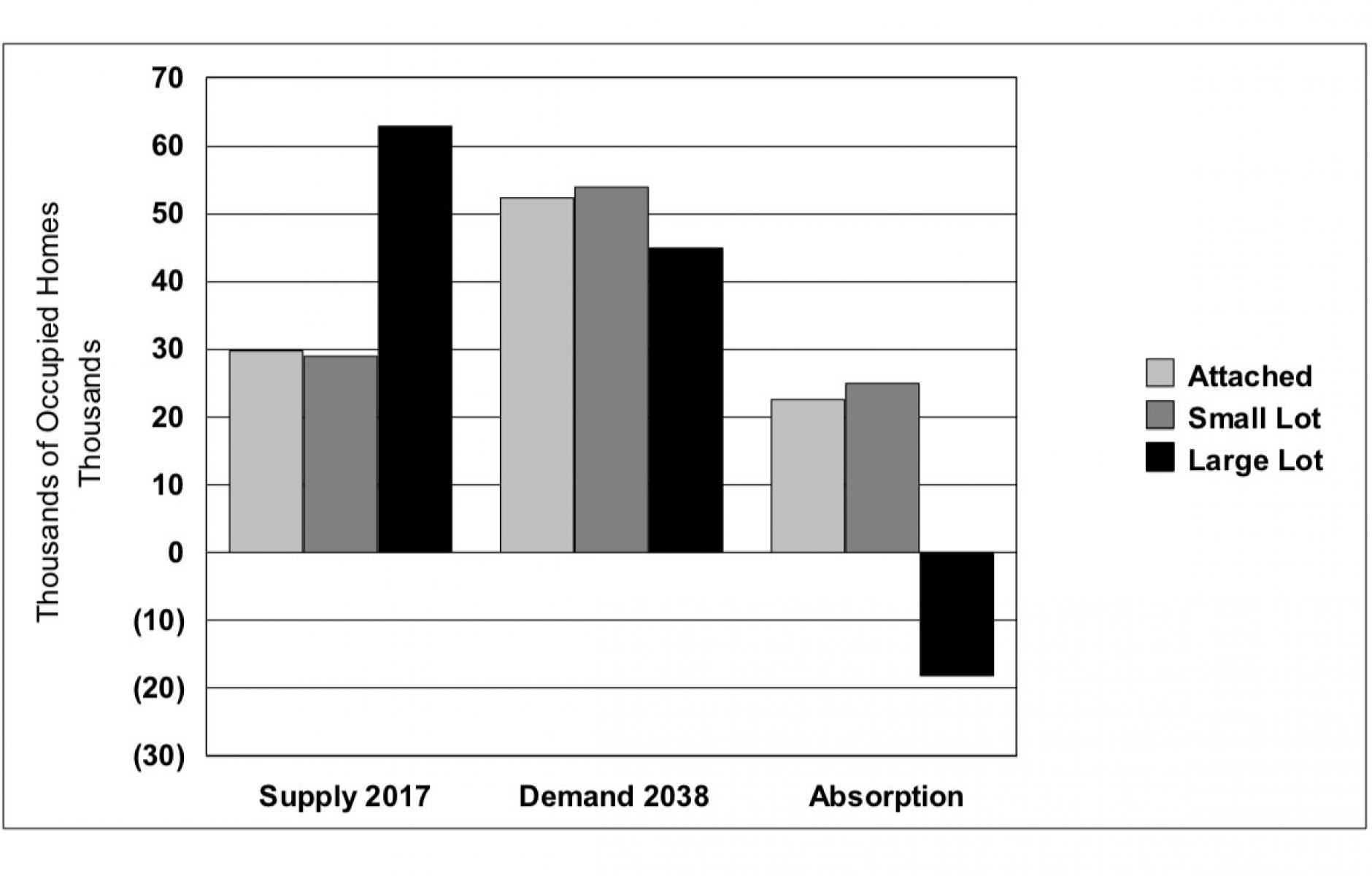

Government at all levels needs to reform zoning, financing, and other policies to head off significant-to-devastating real estate consequences, he says. He calls the impending problem “The Great Senior Short-Sale” in a paper published in the Journal of Comparative Urban Law and Policy. Nelson reports that “by 2038 there may be as many as 18 million more homes on large lots than the market wants. Aging- in-place or not, the sheer number of seniors leaving their homes will simply overrun the number of younger generation buyers.” Between 2017 and 2038 there will need to be:

- 23 million more attached homes and

- 25 million more small lot homes but

- 18 million fewer large lot homes.

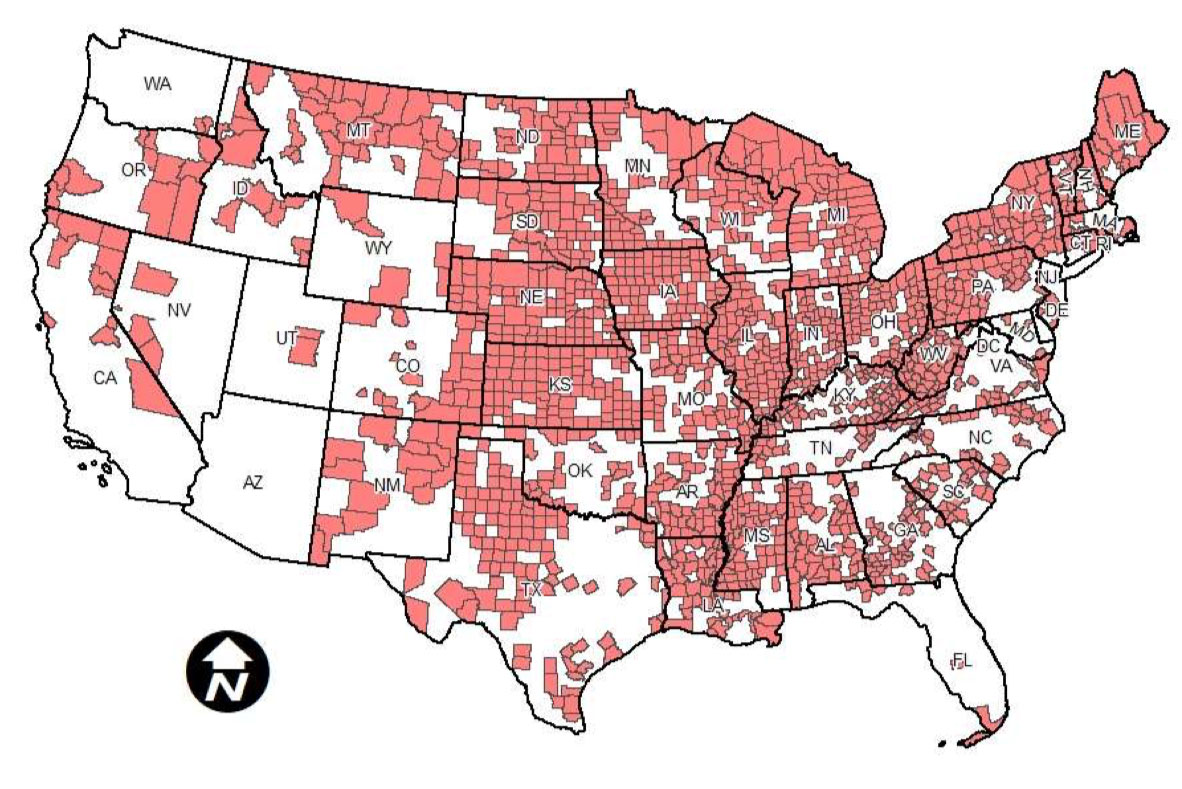

In addition, the entire new demand for homes up to the middle of the 21st Century will be for houses in walkable communities, due to changing generational preferences. The market imbalance will not be felt in every part of the US. He describes three geographic scenarios:

- Markets growing faster than the national average will likely not face much of a problem.

- Markets growing, but unevenly, will face significant problems in submarkets, especially on the suburban fringe.

- Markets stagnating or losing population will face devastating consequences from the Great Senior Short Sale.

Nelson recommends a variety of policy prescriptions in geographic areas described in 2 and 3 above. Many of these policy changes are in line with new urban principles and make sense for a variety of reasons. These include:

- Reforming zoning codes to allow for “missing middle” housing types such as accessory dwelling units, apartments, duplexes and other multiplexes, and other housing types that will be in greater demand. These changes are already happening in Oregon, Minneapolis, Seattle, Atlanta, and other places—and such reforms could sweep the nation.

- Changing state laws to supersede homeowners’ association rules to allow McMansions to be converted to apartments, or retrofitted to include an apartment.

- Encourage excess bedrooms, millions of which are in homes owned by senior citizens, to be used.

- Encourage the retrofit of dead or dying suburban shopping malls and strips centers into walkable urban centers with multifamily housing and a mix of uses.

- Loosen mortgage underwriting standards in ways that would not lead to a repeat of the 2008 housing crash.

- In markets that are declining or stagnating, Nelson proposes a more forceful response from the federal government, including buy-back programs for houses in flood-prone or environmentally sensitive areas.

The good news is the “short sale” would make housing more affordable—but this is a double-edged sword, he says. “The silver lining of the looming glut of housing is that prices will be driven down and homeownership will be made more affordable (or less unaffordable) for those who are in the market. On the other hand, the looming glut may trigger the next recession.”

Because of demographic shifts will come slowly, this housing mismatch will take the nation by surprise if we don’t get ahead of it with changes in policy, Nelson says.