Factory-built affordability: Are we there yet?

On March 22, 2021, more than a decade after many assumed such an event would become routine, a small, factory-built home designed to the standards of custom, site-built homes and targeted for infill affordability was lowered onto an infill site in Ocean Springs, Mississippi.

“It was a long time coming,” said Ocean Springs architect Bruce Tolar, who designed the new 504-sq. ft. cottage built in Franklin Homes’ factory in Russellville, Alabama.

Tolar’s design and its factory fulfillment signal a narrowing of the gap between cultures—the one inspired by the architectural traditions of site-built homes and the one shaped by the engineering constraints of factory construction. The moment has a back story. It’s animated by lessons learned and relationships built from the Katrina Cottage movement in the aftermath of the 2005 storm that devastated Coastal Mississippi and flooded New Orleans. And it suggests something hopeful for the future, a strengthening of one component in an affordable housing toolkit in high demand in the post-pandemic era.

A legacy from a storm

The Katrina Cottage effort emerged from the Mississippi Renewal Forum, a mega-charrette organized by CNU at the request of then-Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour and led by architect/planner Andrés Duany, a CNU founder. Duany recruited design and planning specialists from around the world and assigned them a range of tasks to guide state and local leaders in post-Katrina recovery and rebuilding.

Many on the architecture team, like Tolar, built careers designing high-end homes, often in new urbanist neo-traditional neighborhoods. What Duany asked was that they apply the same standards of appealing design and quality materials to smaller-scale Katrina Cottages capable of serving duel purposes—providing displaced residents’ with temporary shelter, then transitioning to permanent neighborhoods.

From the beginning, it was a bang-for-the-buck ambition: Create a safer, more durable alternative to FEMA trailers in the short run, then use them to help replace tens of thousands of homes lost in the storm. If speed and efficiency were crucial, then why not look to the building sector that offered those advantages? That is how new urbanized designers, including Duany himself, began a long and often frustrating exploration of potential partnerships with the manufactured housing industry.

“If we were going to get the most number of cottages to those who needed them in the months after the storm,” said Tolar, “we needed to build as many as possible in factories.” And to their credit, Mississippi and Louisiana elected officials used their clout in Washington to secure $400 million for the cause. Only, by the time all the agencies and officials had signed off on each step, designs were negotiated with factories, and cottages began rolling off the line, it was 2008. Other funding had helped the displaced find new places. And with the sense of urgency diminished, the longing for normalcy set in—including a normalcy that assigned manufactured homes to the category of “trailer park” housing unwelcome in or close to established neighborhoods.

Hence the two-word explanation for why it’s taken so long for architects, factory production companies, and end customers to agree on what constitutes aesthetic and structural quality: “The stigma, that’s something we still struggle with,” said Grant Beck, vice-president for strategic partnerships with Next Step USA, a nonprofit that serves as a networker/mediator between the factory-built home industry and prospective home owners and affordable housing groups.

A convergence of interests

Even before Katrina Cottage designers began concentrating on the design and materials challenges, the industry was upgrading structural integrity, thanks to standards imposed by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s HUD Code in 1976, followed by an update in 1994. Still, both the interior feel and the exterior look of most units coming out of factories argued “engineered product” more convincingly than quality “home.”

Understandably, that was especially the case for products determined to rigorously maintain the industry’s low-cost advantages over site-built competition. “Even five years ago, there was still this stigma about factory-built housing, even though the quality of homes coming out of the factories has vastly improved,” said Peter James, vice president of engineering, quality, and special projects for Franklin Homes. “And now we’re getting designs that are even more pleasing to the eye.”

James’s company has its own connection to Mississippi‘s post-Katrina recovery and rebuilding period. Franklin Homes was acquired in 2015 by C3 Design, Inc., a Mississippi company founded by Fred E. Carl, Jr. Karl was Gov. Barbour’s appointee to oversee replacement housing that included the development of the factory-built Mississippi Cottages financed through the $400 million federal appropriation.

Though they lacked some design elements in the Katrina Cottage portfolio and arrived too late to have the hoped-for impact in the emergency housing crisis, they hinted at what might be possible for the larger and longer lasting affordability crunch. And for Tolar and partnerships he helped stitch together, they represented an opportunity for proof of concept for what they’d dreamed up at the Mississippi Renewal Forum.

Eight of the factory-built cottages found places in Cottage Square, a two-acre undeveloped parcel within easy biking and walking distance from Ocean Springs’ historic downtown. Combined with site-built examples of original Katrina Cottage designs, the manufactured cottages contributed to a range of examples of how well-designed, small-scale homes could satisfy goals of affordability, urban neighborhood density, and distinctive character all at once. And in the process, they achieved the goal of designing, then constructing, a house in a factory that could not be distinguished from one built on site.

A breakthrough moment

After the last of the Mississippi Cottages were auctioned off in 2011, there were no more factory-built examples to expand the “show rooms” of the Katrina Cottage legacy. Not until March of this year, when Tolar’s one-bedroom version made the journey from the Alabama factory to an expanded Cottage Square.

“It was exciting to see it arrive,” said Tolar. “We had the foundation already prepared. So, it took just two hours total and only 22 minutes to set the cottage once the crane was in position.” That brief time underlines an advantage that factory construction has never relinquished.

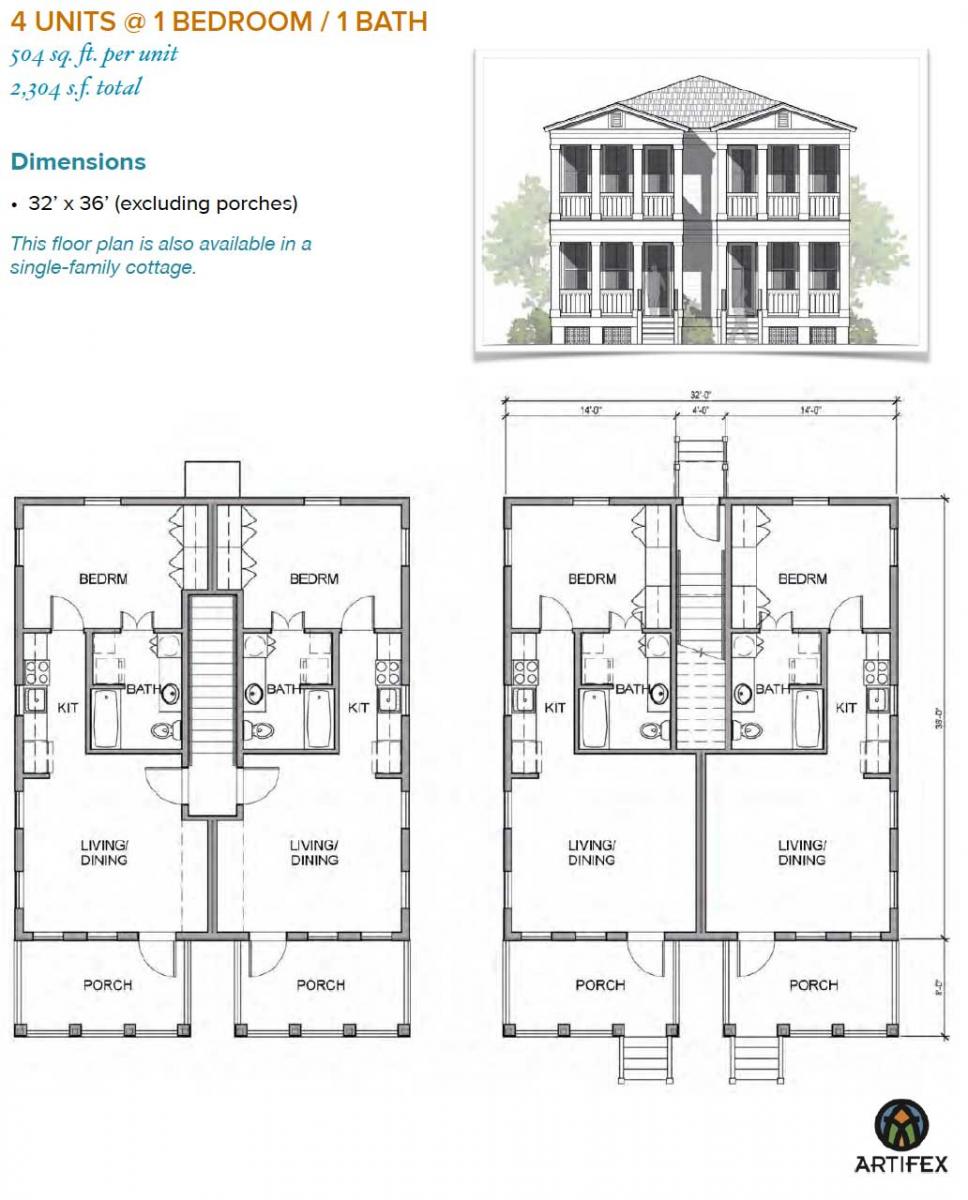

Tolar’s new cottage is built to storm zone housing codes. It boasts metal roofs, nine-foot ceilings, and ample wood-clad windows. The premium model comes with granite counter tops and fixtures, with other selected upgrades available at the factory. There are two and three-bedroom versions in the queue. And units can be stacked to create two and three-story multifamily structures.

Delivered costs to prospective builders are in the range of $110,000 for the one-bedroom and $130,000 for the three-bedroom. That includes the base cottage, standard finishes package, appliances, and freight. It does not include state tax, where applicable, or site-related costs such as site prep, foundation, setting of the cottage, utility connections, and hardscape. Delivered costs typically make up 75 percent of total construction costs. Site-related costs account for the remaining 25 percent. (Costs will vary, also depending on distance from the factory and the currently unpredictable prices of materials—particularly wood. Soft costs and land are factored in separately.)

Defining “affordability” for opportunity

Over time, volume orders like those made possible by the post-Katrina federal appropriation might lower those costs, especially as new factories come on line with expanded flexibility to deal with design elements that architects and buyers demand. But both Tolar and James caution against imagining factory-built approaches alone will solve the affordable housing problem.

Housing most in demand and where new urbanists focus their efforts is located where everyday destinations are close enough to be reached by transit, biking, and walking. Housing costs in those places are heavily determined by the cost of land, a commodity unaffected by the efficiencies of mass production.

Instead, recognition is growing that “affordable housing” applies to a wider range of needs and potential customers than those addressed by heavily subsidized public housing. With the growing gap between household incomes and housing costs nationwide, said Next Step’s Beck, “the goal line keeps moving for those who can afford a new home. It’s not just the lower income families that are affected by the gap, it’s becoming the middle class.” Whereas most affordable housing programs target those making 80 percent or less of an area’s median income (AMI), those making 100-120 percent of AMI “is now a tough demographic to serve,” said Beck.

Into the future

At this stage of the emerging market for attainable housing, that’s where an opportunity lies. “Yes, I think there is a niche,” said Next Step vice-president Amy Barnard. “We’re seeing that narrative (of millennials and service workers, retirees, and others willing to exchange square footage for access to urban amenities) play out across the country. We see an opportunity and a real need for developers to get into this space.”

Tolar—with Atlanta-based R. John Anderson, founder of the small developers movement within New Urbanism; New York architect David Kim; and Columbus, Georgia, commercial developer Will Burgin—formed a new firm, Artifex, to claim territory in that space. They’re working with clients in Georgia, Tennessee, Texas and elsewhere to develop mixed-use, mixed-income urban infill aimed at households earning 80-120 percent AMI.

In the most expensive markets and locations, non-profit or government agencies likely will still have to help close gaps between what’s required and what’s economically feasible for developers and factories. But subsidies to address this niche are likely to be much less than those needed to fund housing for lower-income households. And, a new generation of factory-built housing suppliers will have the chance to compete with site builders for deeper subsidies for needier homeowners and renters.

Next Step is already coaching coalitions of developers with similar goals in California, Maryland, and other states. In Michigan, the State Housing Development Authority is setting aside $2 million for demonstration projects for factory-built housing. And Andrés Duany, the guy who helped launch the conversation in New Urbanism back in 2005, has had his team of designers pushing the envelope on what might be possible if the convergence with the manufactured housing industry advances.

“It’s taken a lot of time to figure out how to do this right,” said Franklin Homes’ Peter James. “But as manufacturing technology becomes more familiar and accepted among single-family and multifamily home builders, more people will have to open their eyes to this building approach so they don’t miss out on the opportunity.”

For more information:

- A multi-linked backgrounder on the 2005 Mississippi Renewal Forum: http://mississippirenewal.com

- A 2015 Katrina Cottage case study on the Lean Urbanism site: http://bit.ly/1Sl5Zx1

- A 2017 “Public Square” interview with Katrina Cottage designers Bruce Tolar and Marianne Cusato: https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2017/03/02/great-idea-cottages-emergency-and-permanent-affordable-housing

- The Artifex firm website: https://www.artifexcottages.com

- The Next Step website: https://nextstepus.org

- The Franklin Homes website: https://www.franklinhomesusa.com