How to prepare communities for climate change

“Think globally, act locally,” has been an environmental mantra for at least 30 years. For local communities, acting on climate change begins with a plan—which makes urban planners a linchpin in this issue. And yet planners may be averse to getting in the middle of another political hot-button topic, especially if they don’t know how effective they can be.

Jason King’s The Climate Planner: Overcoming Pushback Against Local Mitigation and Adaptation Plans, recently published by Routledge, demonstrates how urban planners can make a visible and important difference through local community actions that address the global climate problem.

Urban planning and design are among the most effective tools in dealing with climate change, because they address mitigation and adaptation—both of which will be necessary in the coming years. Mitigation is global in scale—it involves the reduction of carbon emissions that are linked to rising global temperatures. Communities can lower emissions in a number of ways—including using the principles of New Urbanism reduce the need for motor vehicle travel.

Adaptation is local. The forms and combinations of adaptation are as varied as local communities themselves. The impacts of adapting are felt locally and tend to become immediately apparent. With adaptation, communities can take control of their own destinies to a degree.

The Climate Planner has many qualities that make it a worthwhile read. King, a principal at the urban design firm Dover, Kohl & Partners in South Miami, Florida, previously worked as a news reporter. The skills he honed in both fields help to organize and clarify a complicated topic with important implications for urban planning.

The Climate Planner is not a scientific book on climate change, but it does address the science in a balanced way. Planners need a good general understanding of climate change science, because opponents to climate change plans will make their own scientific claims, often in public meetings. Making the case for action means addressing facts about this issue in a way that leads to consensus, even if many residents are skeptical. He doesn’t shy away from the complications of science and politics around the issue, and he manages to convey the urgency of action without being overly judgmental of people on either side, all of whom have their prejudices at times. “One of the things that makes me optimistic about the climate change fight is that we’re all at fault and all in it together,” he writes.

A better understanding of climate science is an incidental benefit of reading The Climate Planner—its major strength is in the stories of King’s personal involvement in communities that have addressed this issue in a meaningful way.

On a receding Gulf coast

One of the memorable stories comes from the bayou in Louisiana, about 20 miles south of New Orleans, where the existence of a town of about 2,000 people is threatened. Jean Lafitte is only about two feet above sea level, spread out over six square miles. Mayor Tim Kerner was committed to convincing a state authority to build 65 miles of levees around the town, but had no success due to the money involved in protecting a relatively small community.

A comprehensive plan led by Dover Kohl, titled Jean Lafitte Tomorrow, proposed an alternative solution—a slow retreat into at one-square mile “heart of town” that could be protected by levees. That levee system was added to the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority’s Coastal Master Plan, and has since been built. Dover Kohl showed the town how making the “heart of town” more compact could accommodate the town’s population over time.

Jean Lafitte has no choice but to face changes in the climate and coastline, and thanks partly to good planning, the town has a more secure future. After shrinking 10 percent in population after Hurricane Katrina, Jean Lafitte grew slowly again in the last decade. The document, which remains the town’s official plan, won a special jury award in the 2014 Charter Awards. “In this age of climate change, the Charter Awards jury saw Jean Lafitte Tomorrow as a compelling and timely parable of new urbanist planning at its best,” CNU notes.

Sunny day flooding

Miami Beach became famous last decade for its “sunny day flooding,” whereby sea water pushes up through drainage pipes and sewer grates to flood the city’s streets during particularly high tides. King lived with his family in Miami Beach for 10 years up to 2018. He and his wife, Pamela, also an urban designer at Dover Kohl, often drove their car through the streets flooded with seawater on their way to work (their Mini Cooper rusted on the undercarriage, similar to cars in the snowy Northeast). Rolling Stone published an article in 2013 about the flooding, concluding that Miami was destined to become “an American Atlantis.”

Philip Levine became mayor that year and began to install pumps, drainage pipes, and backflow preventer valves. Then the city began a program of raising streets to a minimum of 3.7 feet, which meant a lift of two feet for many streets. The cost of the program was $400 million, paid for locally, and many of the streets that flooded are no longer doing so. “At best, the new system only bought select areas of Miami Beach 40 to 50 years without sunny day flooding, but, locally, it felt like a step in the right direction,” says King.

During this time, Dover Kohl led a planning effort for the city’s North Beach (NoBe) area, a 1,100-acre plan that sets the stage for higher construction standards to withstand sea-level rise—while strengthening defenses like sea walls, mangrove islands, and barrier beaches. Miami Beach continues to raise streets and adapt to climate change. Although the city may eventually succumb to rising seas, that time may be a long way off. The Netherlands, for example, has been winning a battle with the sea for centuries.

Receiver cities

Cities that are less in harm’s way may be impacted in other ways, as shown by Hammond, Louisiana, which is located 45 miles northwest of New Orleans. Dover, Kohl was hired by Hammond to write a plan and code for the city in 2009, when it was experiencing post-Katrina growth.

Located 45 feet above sea level, Hammond is what some call a “receiver city,” because it is poised to grow in the event that people relocate away from low-lying coastal cities or places with other climate problems. Receiver cities often have to rethink their growth patterns to accommodate potential migrants.

Hammond’s form-based code (FBC) is designed to promote new urban development downtown, allow for growth in “missing middle” housing types in residential neighborhoods, and enable the transformation of single-use commercial corridors into mixed-use places.

In the 10 years since the plan was adopted, Hammond’s growth has returned to normal, as the immediate impact of Katrina and subsequent storms has faded. Its downtown has transformed and missing middle housing like accessory dwelling units are being built in residential neighborhoods.

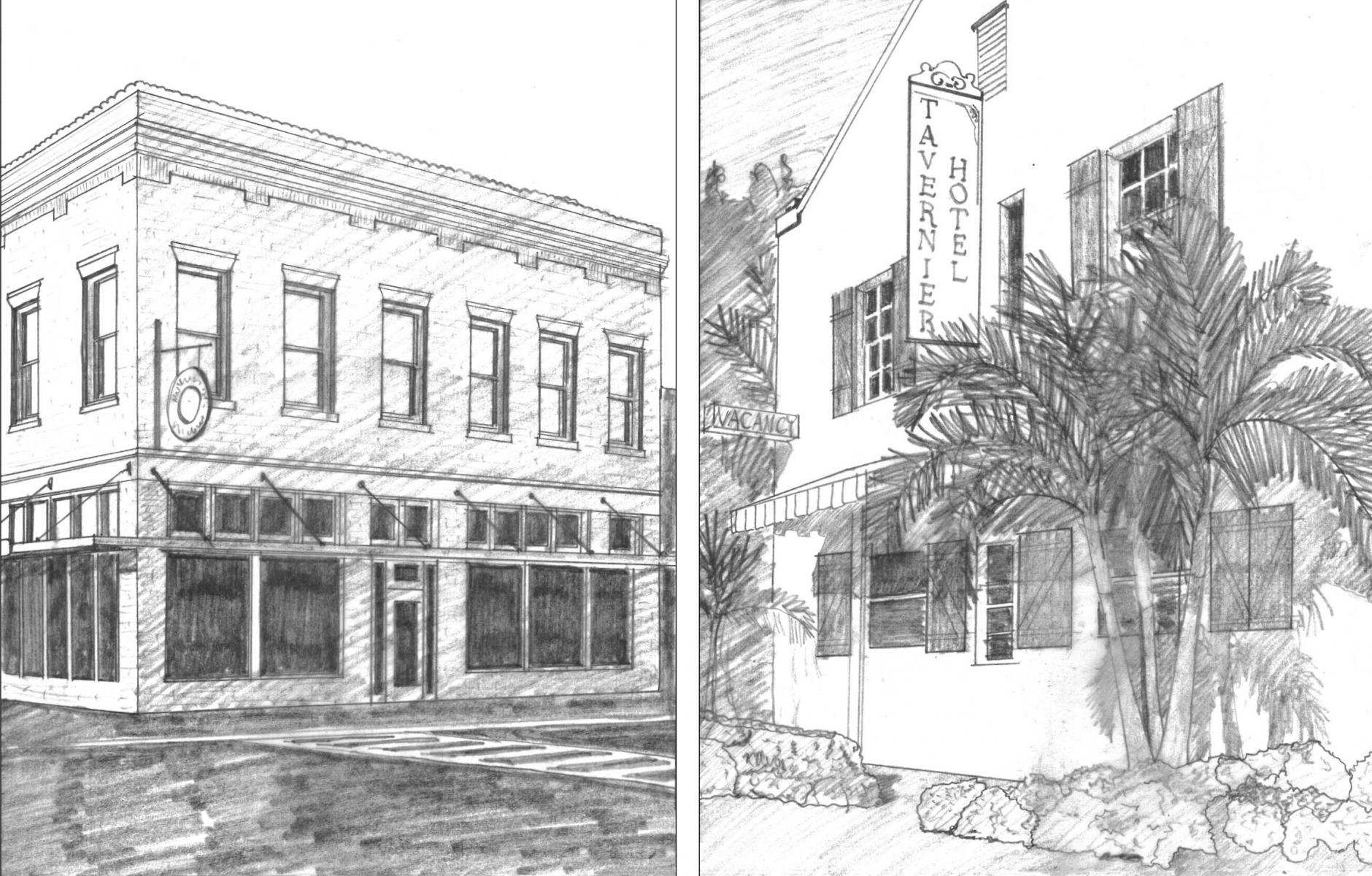

“Thanks in large part to historic tax credits and façade grants recommended by the plan, 90 percent of historic buildings in Hammond are now occupied,” King writes. Plans to bring mixed-use to commercial corridors has only marginally succeeded, with the construction of a few multifamily buildings with improved urban design. If and when Hammond once again receives climate migrants, these areas could accommodate considerable affordable housing for the rising population.

Because of the added challenges of addressing a worldwide issue with local implications, planners may be tempted to ignore climate change. I was surprised to learn that the first draft of a Dover Kohl plan for revitalizing Panama City, Florida, after Hurricane Michael (2018) did not directly address climate change or rising sea levels. A Strategic Vision for Panama City’s Historic Downtown and its Waterfront won a CNU Charter Award in 2020, partly for its frank discussion of 2100 sea-level scenarios. The planners were encouraged to ignore the issue, but eventually tackled it head-on after soul-searching. The plan is much stronger for it.

King examines this topic from many angles. Other stories from The Climate Planner focus on inland communities that may be dealing with heat-related stresses to people and landscape, or water issues. Near the end of the book, King outlines a step-by-step process of how to co-author a climate change plan. This quick guide will come in handy for planners authoring plans in an era of rising global temperatures.

Whether you read the book cover-to-cover or use it as a handy reference or both, The Climate Planner is an important addition to the bookshelf of urban planners and designers.