Minneapolis zoning reform put on ice

At a time when the need for zoning reform is gaining intellectual currency and credibility, one of the most important city land-use regulatory changes of recent years has suffered a legal setback.

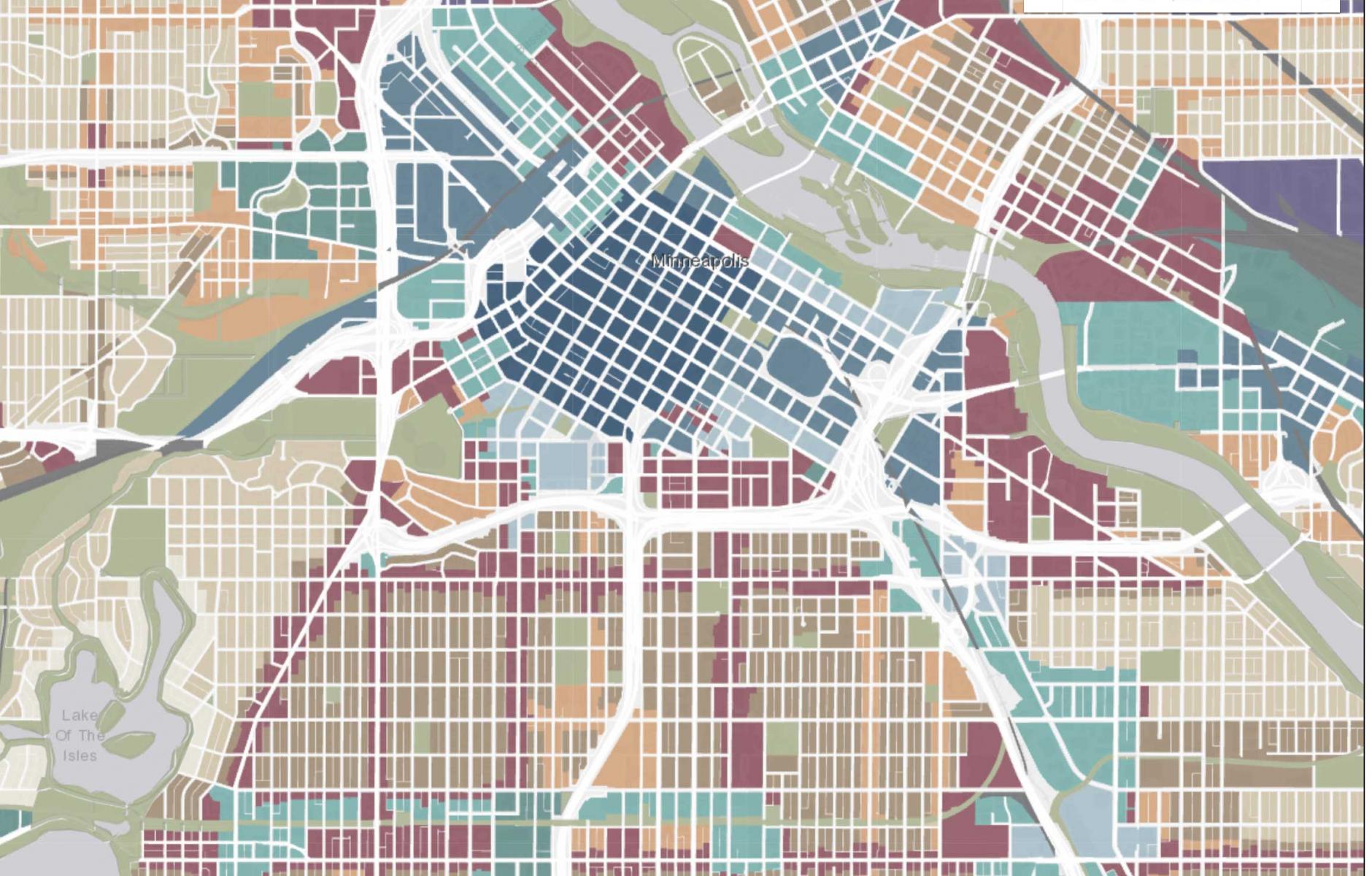

The Minneapolis 2040 plan, which effectively got rid of exclusive single-family zoning in the city starting in 2020, was put on hold in mid-June by a judge who ruled in favor of plaintiffs in a lawsuit.

Hennepin County Judge Joseph Klein said the city would have to study the environmental impacts of the plan prior to further implementation. The suit was brought by Smart Growth Minneapolis, Audubon Chapter of Minneapolis, and Minnesota Citizens for Protection of Migratory Birds, who sued the city in 2018, just prior to City Council adoption.

The law allows two to three units on single family lots, which could theoretically add 150,000 living spaces to Minneapolis. But in two years, the reforms have led to 104 new duplex and triplex units. The plan also allows small multifamily buildings along transit corridors, among other reforms. At the current rate, it would take many centuries for all of the theoretical units to be built—and in that time all social, market, technological, and regulatory conditions will have changed many times. Likely, there would be no zoning in the city well before that happens. And yet the judge is asking the city to do an environmental review in advance. The city argues that environmental review can be done, as necessary, as projects are proposed.

Advocates for loosening up exclusionary zoning requirements reacted with dismay, and hope that the ruling will not stand.

“Now they have seemingly buffaloed a judge into ruling, essentially, that cities must conduct exhaustive and expensive studies into every hypothetical impact that might arise from the act of planning for the future,” wrote Alex Scheiferdecker of Streets.mn. “I’m not a lawyer, but it’s a ruling that seems so genuinely nutty that there’s reason to hope it’ll ultimately be reversed.”

Reason Magazine notes other absurdities of the decision.

“Minneapolis had been chipping away at parking minimums since 2009. The Minneapolis 2040 plan got rid of them entirely. Because Klein's decision requires Minneapolis to revert to its pre-Minneapolis 2040 zoning policies, it is possible that developers will be forced to include parking in their buildings again because the city didn't study the environmental impacts of not requiring parking.”

That low-density housing restrictions don’t help the environment has been well established. That’s because the new housing does not go away, but is pushed to the outer suburbs—where the residents impact more land, use more fossil fuels, and generate more carbon emissions. As Reason pointed out:

“It's true that more development in Minneapolis might mean less tree cover and more strain on the city's sewer system. But the people who would have lived in those new homes don't just disappear because the homes do. They will instead move to places where homes are allowed to be built. Often that's going to be suburban developments on previously undeveloped that will have an even greater impact on the environment.”

Scheiferdecker notes that so far, the 2040 plan has not resulted in a surge in housing production—but the last two years have coincided with a pandemic and significant unrest following the death of George Floyd. The plan's real benefit is that it offers the city and its residents more flexibility in dealing with climate change and an uncertain future, he says.

“One of the absurdities of the district court decision that halted the implementation of the Minneapolis 2040 plan is its insistence on assessing the plan as if every possible housing unit was built at once. This is a ridiculous standard. Planning doesn’t work that way. A plan like Minneapolis 2040 is, at its core, about things that are hard to define and measure. Things like increasing flexibility for an unknowable future. Things like increasing choices for a multiplicity of actors. The purpose of the plan is to bend the arc of the future, not to rigidly shape it. It cannot be judged any other way.”

Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey has promised that the city will appeal.