Financial fragility is to blame for Jackson’s water crisis

Note: This article first appeared on Strong Towns. Public Square editor Robert Steuteville is on leave through the last week of October.

I’ve spent some time trying to understand what has happened with the water system in Jackson, Mississippi. For locals who have lived through the long unfolding drama, any single explanation is going to fall short, and it should. Before starting, I want to pause and recognize the hardship residents of Jackson have experienced, not just in this recent crisis but for many years. They deserve better.

In any situation like this, there are proximate causes and then underlying causes. The former seem fairly straightforward and are typical of the kind of failures experienced when systems are stretched too thin. A flood inundated one water treatment facility, rendering it inoperable. Sediment and debris carried by the flood made the city’s reservoir a muddy mess.

A second treatment facility, operating alone, may have been able to keep up with demand in normal conditions, but not in a flood situation where that muddy water requires lots of extra treatment. It seems that the pumps at the secondary facility have burned out or otherwise failed, causing the water distribution system to lose pressure—a situation that could be remedied but only at great cost in terms of time and money. Jackson doesn’t have either.

There are many people who insist that Strong Towns has overstated the degree of municipal insolvency in American cities, and that, if we were right, there should be a wave of municipal defaults and bankruptcies. I’ve never claimed that would happen. Jackson’s failing water system is what default looks like. The city can’t provide the drinking water people depend on, yet S&P has given them an investment grade bond rating of A+ and last December, Moody’s gave Jackson’s water enterprise fund a rating of Ba2, just slightly below investment grade.

The bond traders will get their money. They always do. The outstanding question for America’s cities continues to be: What do your residents get in return? In Jackson, it has been decades of safety violations, unreliable service, and rising utility rates. And lots of debt. The financial system—like nearly everyone else—has preyed on Jackson, making the city more and more fragile each year that passes.

This has not kept the current political zeitgeist from also trying to cash in on Jackson’s hardship. There are three underlying causes being put forth to explain what has happened in Jackson and, simultaneously, motivate voters outside of Jackson to support one national political approach over another. All three are a distraction, at best.

The first is climate change, the notion that extreme weather events are going to be more frequent due to the impacts of anthropogenic climate change and this will cause infrastructure failure. An article in Bloombergmakes the case that “extreme weather” was a factor for Jackson, that the city’s water system failure is “a stark warning of trouble to come as climate change piles new stress onto the essential services Americans rely on every day.”

Yet, three paragraphs later, the same article states that “the rain wasn’t record-setting or even as bad as initially predicted.” The climate change narrative is very compelling for a lot of people, but here it is a distraction. Even if there was no climate change, Jackson’s infrastructure is still failing. And since the stock infrastructure response to climate change is to build more infrastructure—bigger, deeper, and stronger infrastructure in order to to withstand nature’s onslaught—then a focus on climate change only makes Jackson’s insolvency problems worse.

The second narrative being used to explain Jackson’s current plight is that of systematic racism. As an article in VOX suggests, “the roots of this crisis run much deeper, and are inextricably tied to white disinvestment from a majority-Black city.” The article states that Jackson’s water system is failing “largely because white flight drained the city of resources” and that the state legislature, dominated by Republicans, has not provided the funding needed to make repairs.

It is undeniable that decades of public and private investment in the Jackson metropolitan area has produced racist outcomes—80% of those trapped in Jackson’s water crisis are Black—but the racial narrative suggests this development pattern has resulted in a lack of resources. It hasn’t. What it has created is a surplus of liabilities: more pipes, pumps, and promises than Jackson has the capacity to make good on. If the federal government swoops in and fixes the system for them, which isn’t going to happen (ask Detroit or Flint), it buys Jackson time, but doesn’t solve the underlying insolvency problem.

A third narrative put forth is one of corruption and incompetence. This narrative isn’t getting traction in respectable circles, but it’s all over social media. I’m going to give it a voice, not because I buy it (it’s also a distraction), but because I think it’s important to understand where we are.

Broadly speaking, people in rural America look at politicians in urban America and see free-spending liberals too distracted by pandering on culture war issues to competently govern. There is some truth to this, but those same people in rural America also seem to expect their local council members to weigh in on gun rights, abortion, and critical race theory instead of focusing on collecting trash, providing safe water, and filling potholes. I go back and forth between these two Americans and find them both bewildering, especially since both casually ignore their own rapidly declining fiscal health. It’s easy to fiddle while Rome burns, especially if you have no clue how to begin putting out the fire.

Like all American cities, Jackson has the wrong business model. Following World War II, cities like Jackson had a development pattern imposed on them that, in the pursuit of national economic growth objectives, added billions of dollars’ worth of financial liabilities to their local balance sheet while simultaneously devaluing their community. All of those miles of roadway, pipe, and sidewalk were added to a tax base that never kept up. And much of the tax base that was there, the most productive part of the community, was torn down for parking lots and silver-bullet projects.

Over time, an enormous backlog of maintenance promises combined with rising tax rates, record amounts of municipal debt, and a stagnating tax base to rob the city of options. Financially, Jackson is really fragile.

Fragile places get hurt. People in fragile places suffer. That’s not a choice, it’s a consequence. And it’s really tragic.

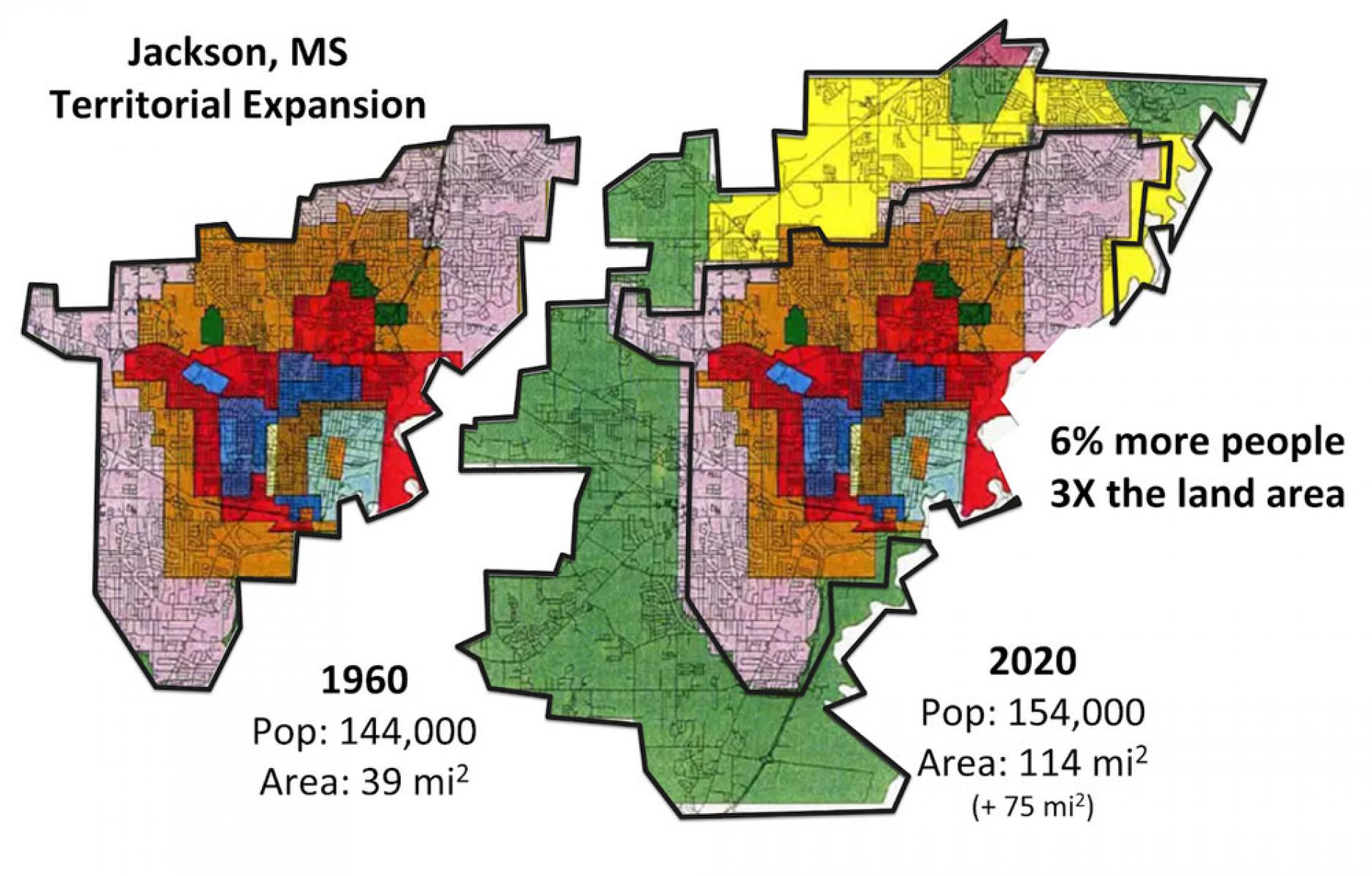

Many people today are focusing on the fact that the city of Jackson has lost population. In recent decades that may be, but it obscures the larger problem. Through annexation and horizontal expansion, Jackson has grown its own footprint many times over. Josh McCarty at Urban3 calculated that between 1960 and 2020 Jackson has tripled in size while adding only 6% more people. More stuff to maintain with fewer people to maintain it is an equation that equals insolvency. That is especially true when the people are poorer than most, but having a marginally wealthier population would, at best, have slowed the rate of decline. It would not have prevented this tragedy.

And understand that, while the city may have lost population, the Jackson metropolitan area didn’t; it has more than quadrupled over the past 70 years. Those places on the periphery of historic Jackson are earlier in the life cycle of the Growth Ponzi Scheme, but the clock is ticking on them, as well. Ultimately, they will prove to be even more financially fragile than Jackson. The Suburban Experiment is a bad business model.

There is one lesson we need to take from the culmination of Jackson’s ongoing water crisis, and it’s very simple: Nobody is coming to save you.

The federal government is not going to bail your community out; the biggest infrastructure bill in history doesn’t even keep up with current rates of infrastructure decline. The state government is also not going to bail you out. They don’t have money, even if they had the inclination to help. The corporate developers can provide you growth, but their success will rarely align with yours. And, of course, the bond market will always pretend to be your friend, with one hand extended and the other holding a baseball bat. Watch your knees.

Nobody is coming to save you and so we need to do this on our own. Focus on what you can do with what you have. Start with the Strong Towns 4-Step Approach. Get a real balance sheet and understand where your community’s wealth is. Stop making things worse—no more annexations, new infrastructure, highway expansions, parking lots, or other unproductive investments. Let your neighborhoods evolve; support success when it emerges. Redirect the tools you have to support your own people.

Get started right now with a Strong Towns approach, the bottom-up revolution your community needs. If you need help, start with the Strong Towns book, our 101 Introduction to Strong Towns course, or join with others near you in a Local Conversation.