Parking reform is snowballing

“Pretty much since the 1950s, nearly every building, whether it is new, or remodeled, has been required by local governments to have a certain number of off-street parking spaces,” notes Catie Gould of the Sightline Institute. These mandates affect the form and cost of housing and commercial properties nationwide—and not in good ways.

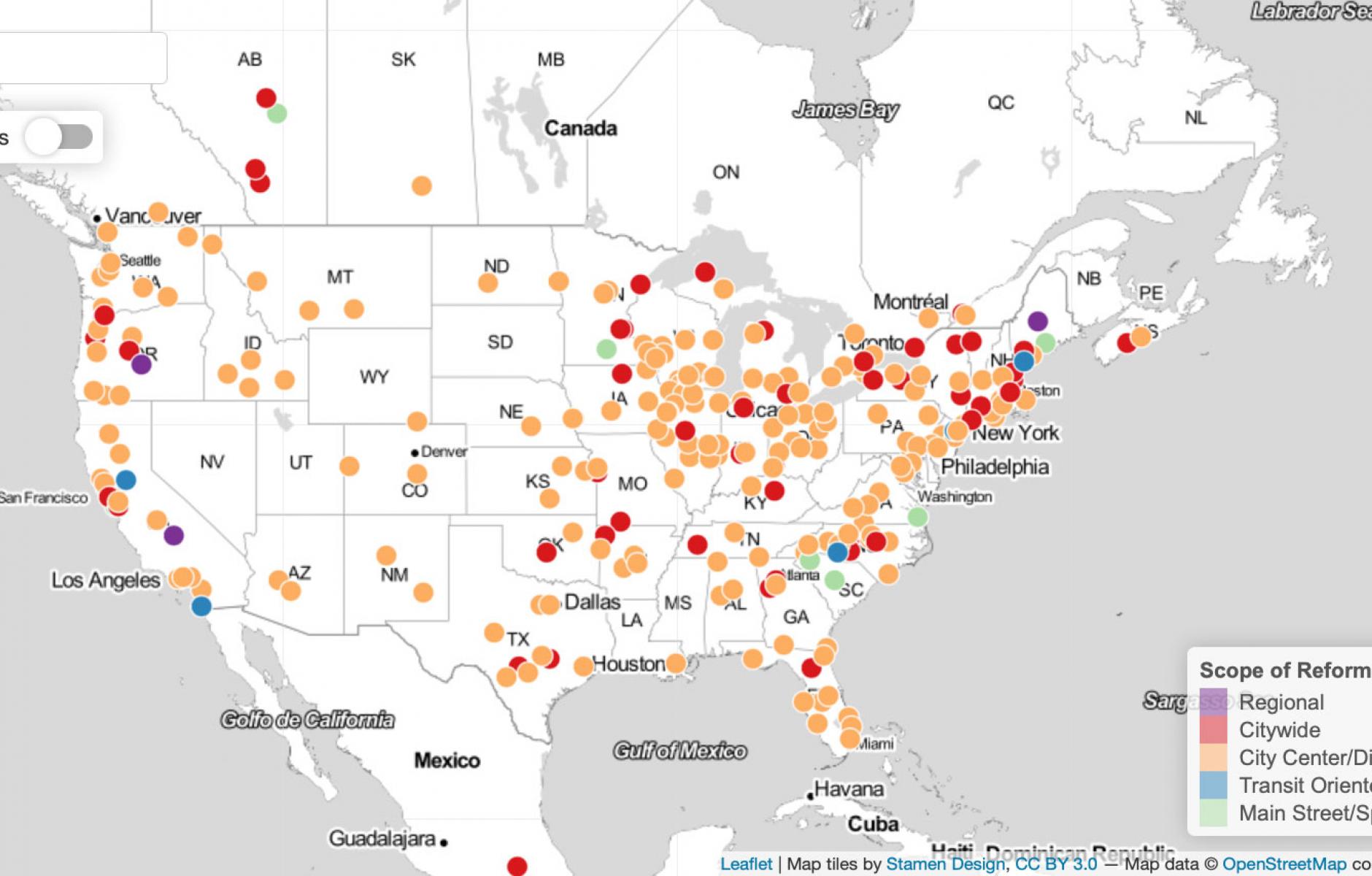

Reform has been building for many years—but recently has hit a critical mass, according to experts. For cities that don’t manage curb parking, the reforms may have unintended consequences. The benefits, however, include more reuse of old buildings, reduction in housing costs and suburban sprawl—and even reduced vehicle miles traveled.

Elimination of off-street parking mandates began in downtown areas, where historic buildings don’t meet modern zoning regulations, according to Gould. “That’s where it started, but it’s not where we are headed. … We are seeing a rapid rise in the number of cities eliminating all parking mandates, citywide. Some examples in the news lately include Anchorage Alaska, which covers an area larger than Rhode Island, and San Jose, California, home to a million people.”

The graph of cities ending parking mandates across the board shows a dramatic acceleration since 2020—higher even in the first quarter of 2023 than in all of 2022. Moreover, a growing number of states are addressing the issue, especially on the West Coast. California and Oregon adopted statewide reform in the second half of 2022, and a handful other states are considering similar legislation—some in other parts of the US. The reforms in California and Oregon are tied to metrics such as distance to frequent transit. California’s law, AB 2097, effectively ends minimum parking requirements throughout much of the largest metropolitan regions. The rules went into effect January 1 in both states. We are in the early stages of a change that will enable types of development that have been scarce for a long time, Gould says.

Parking reform was exclusively a local issue until recently, but it has become linked to larger issues that are of interest to state legislators, according to Tony Jordan, president of the Parking Reform Network. “It’s not just housing, but also climate. And people are more aware of the impacts of automobile centric development in general, which is providing energy to the issue. These issues are percolating up to the statewide offices.”

More middle-class people are being hurt by high housing costs, which makes them more open to parking reform, says Patrick Siegman, an economist and planner who has long focused on parking. Missing middle housing has become a well-known term and desirable goal, and achieving that is helped by the elimination of parking mandates combined with on-street parking management, he explains: “If you want to restore the practice of building missing middle housing … you need to learn how to manage curb parking well.”

Siegman raises an often-overlooked topic, the management of curbside parking spaces. This issue is critical in communities where empty parking spaces at the curb are scarce. Cities should set the price of curbside parking at a level that maintains one or two open parking spaces on every block, at most times. (In neighborhoods with no scarcity of curbside parking, the price can be zero).

Berkeley, California, is one example where downtown parking was priced using this method, which has made finding a parking space much easier, and also encouraged people to park in underutilized parking garages. A surprising amount of traffic downtown consists of people circling for parking spaces. In Berkeley, the variable-price for parking has reduced vehicle miles traveled downtown by 693,000 miles a year, according to one analysis, Siegman reports (that equals 238 trips from New York City to San Francisco). A similar program in San Francisco has increased urban retail sales as measured in sales tax revenues, he says. “If businesses are afraid of making too much money, don’t do demand-based pricing,” Siegman says.

Other good techniques are parking benefit districts, where the parking revenues provide services for the particular neighborhood or downtown (making parking reform more politically feasible), and residential parking permits (these should only be given out in proportion to the available curb spaces in front of a property), Siegman explains.

Parking reform is gaining momentum for several reasons. The fact that so many cities have now eliminated parking mandates in part or all of their jurisdictions is having a snowballing effect. When cities like Buffalo, New York; Hartford, Connecticut; and Fayetteville, Arkansas, got rid of such regulations six to eight years ago, few serious problems resulted, the experts say. On the contrary, a lot of good has been documented. These cities have found that vacant historic properties are being used at greater rates, Gould says.

Nor have developers simply stopped building parking, she says. Most new buildings in Buffalo (83 percent) have parking, while 53 percent have built as much as the former requirements called for. However, many mixed-use projects have built less parking and benefited greatly from the reforms.

Local officials trying to encourage more housing supply are increasingly seeing parking policy as a means toward that goal—with little cost and substantial benefit. “Cities that are in the middle of long-term comprehensive plans are realizing that they are behind the curve now, and are just going for full repeal,” Jordan says. He adds that state-level reforms create political cover for municipalities that want to enact reforms. Additionally, a growing number of housing advocates are organizing around the parking issue, he says.

All of the experts cite Donald Shoup, author of The High Cost of Free Parking and Parking and the City, as the primary influencer in this trend. The first book came out nearly 18 years ago and has had an enduring impact.

Watch Gould, Siegman, and Jordan discuss parking reform trends in CNU’s On the Park Bench webinar series: