Rural urbanist towns: A contradiction or the future?

Often when we think about rural towns in the United States, we imagine a single gas station, a small diner, a few fast food chains at the highway exit, and a couple scattered big-box stores with vast parking lots. This generally demonstrates a lack of walkability, entertainment/shopping/dining options, and (most importantly) a sense of community.

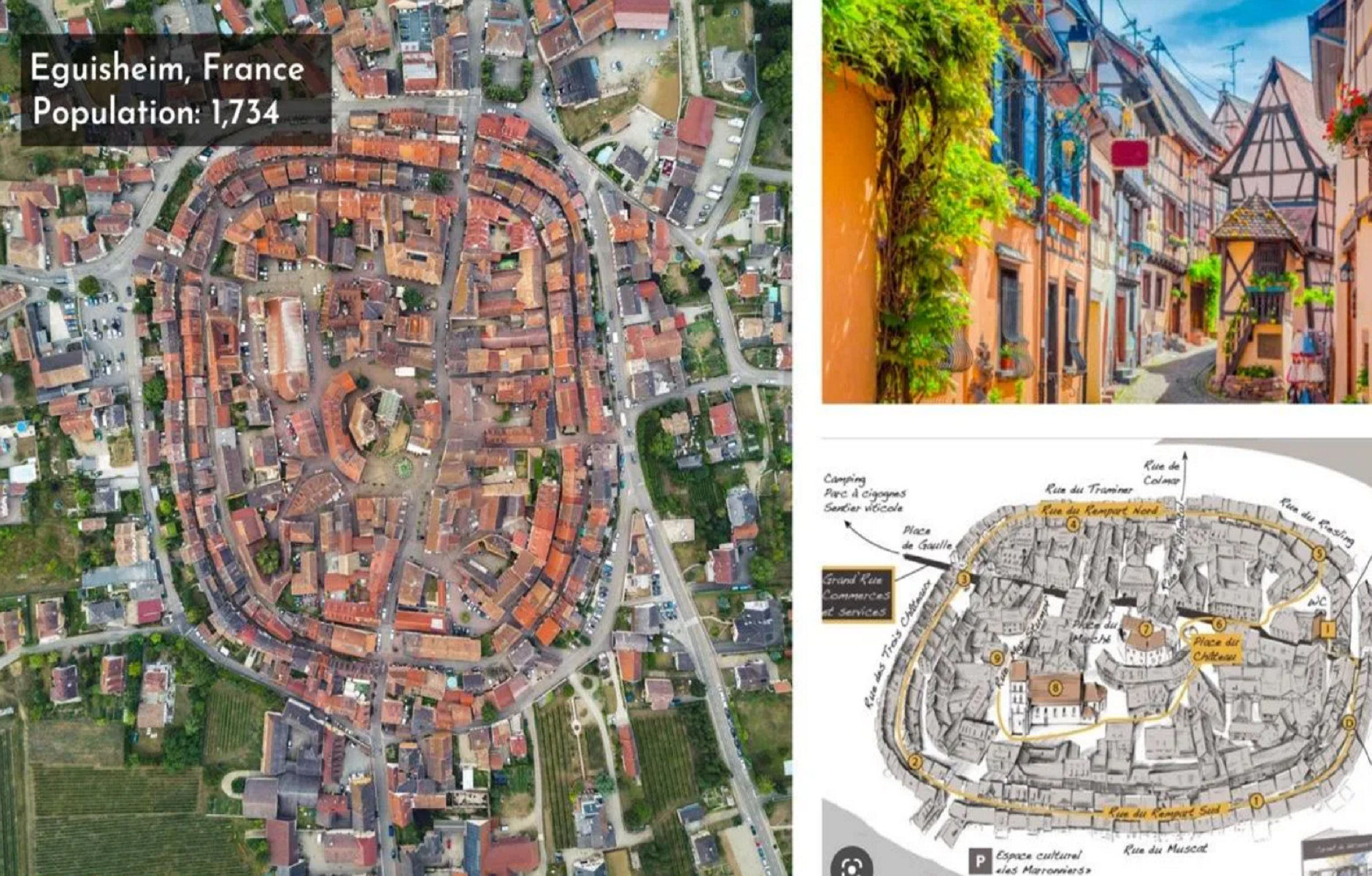

In contrast, when we think about a rural European town, we tend to think of walkable narrow streets lined with charming houses, a central square with a fountain or statue, a historical church or town hall, and small independent shops, cafes, and restaurants with a strong sense of community and rich history. These are some of the foundational characteristics of “New Urbanism,” which harken back to this historical style of urban development.

But can typical rural towns in America match the walkable and vibrant atmosphere similar to their European counterparts?

First, it’s important to understand the underlying reasons why most of America’s rural towns experience deficiencies whereas Europe’s boast strength.

The rise of the automobile.

As a brief history - before the invention of the automobile, towns were developed compactly with often narrow and winding streets, which made them conducive to walking. Buildings were built close to the street, with storefronts on the ground level and homes or businesses above. This created a mix of uses in the same area, making it easy for people to walk to the places they needed to go, such as a grocery store, a church, or a school.

This is commonly seen in towns and villages throughout Europe as many of these European towns were built long before the automobile - with some being built thousands of years before the automobile. One notable example is Hallstatt, Austria, which was settled upwards of 7,000 years ago. This forced European towns and cities to develop in a way that is highly walkable.

In contrast to the thousands of years of urban development before the invention of the automobile, most American towns had a couple hundred years at best, with many seeing most of their growth after the invention of the car. In other words, the total time of American urban development in absence of the car is a fraction of that compared to European towns, resulting in development patterns catering to drivers more often than walkers.

Exceptions to this in the US include, but are not limited to:

- Small towns with constricted geography (water, mountains, etc) like Bisbee, Arizona or Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania - both constricted by mountains.

- Native American settlements established thousands of years ago such as the historical site of Taos, New Mexico.

- Colonial towns such as Easton, Pennsylvania.

In addition to this, many existing towns were structurally changed to favor the automobile once it was invented. The construction of the interstate highway system in the United States, which began in the 1950s, facilitated long-distance travel by car and often routed through towns as a means to connect them. However, it often changed the town’s urban fabric for the worse in regard to walkability by dividing neighborhoods with large structures and high-speed vehicle traffic.

The fall of railroad transportation.

Before the fall of passenger railroads in rural American towns, many communities were designed around train stations, with the main street and commercial district located within walking distance of the station. This enabled walkability by design, allowing residents to easily access goods and services as well as work and leisure opportunities without the need for a car. However, as the interstate highway system expanded, train ridership fell as the automobile grew in popularity. Passenger trains were discontinued rapidly and “between 1960 and 1980, approximately one fourth of the nation's route miles were abandoned.”

This resulted in a stronger dependence on cars, a de-emphasis on the rural urban core around the train stop, and less walkable communities as sprawling car-centric development became the norm.

Industrialization.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the United States underwent a period of rapid industrialization. This led to a significant shift in the population as people began to migrate from rural areas to cities.

Several forces worked in tandem to expedite and solidify the mass migration from rural communities to urban areas. Firstly, agricultural technology became more advanced, meaning fewer people were required to work in rural areas. Currently farmers and ranchers make up just 1.3% of the US labor force, down from 83% in the early 1800’s. At the same time, with the advent of new technologies and production methods, factories were able to produce goods more efficiently and on a larger scale. This led to a demand for a large and skilled labor force, which was primarily found in cities. Lastly, the final shift in our economy from industrial to service-based continued to favor urban over rural due in part to agglomeration economics. Companies have a large incentive to cluster in major urban centers with other similar companies to benefit from shared talent pools of specialized workers, higher productivity, and the sharing of ideas. Examples of this include Silicon Valley for technology and New York City for finance.

With reduced populations and fewer job opportunities, rural communities began to struggle. Businesses in the town center began to close, houses were abandoned, and urban decay became increasingly commonplace. This effect was exacerbated by the sprawling nature of development as a result of auto-dependency. These key businesses in the center of rural communities could no longer rely on local foot-traffic in addition to new competition with the convenience of national fast food restaurants and big-box stores colonizing these communities.

The Solution

So how can rural American towns practice new urbanism and become vibrant, charming, and community-focused? Here are five key strategies:

- Creative re-use of the existing historical structures in the downtown core

- Repurposing existing lost space in the downtown for commercial and pedestrian use

- Expanding the network of sidewalks and bicycle lanes to promote pedestrian activity

- Pedestrian amenities including outdoor seating to increase activity in the downtown

- Diagonal parking to allow for more cars in less space

Below are specific examples of these five strategies in use:

In Opticos Design’s revitalization project of Kingsburg, California, all five of these strategies were used to foster the downtown’s revitalization and enhance its presence and significance within California’s Central Valley.

In another example, Biddeford, Maine, embarked on significant urban renewal projects with the goal of appealing to local residents, newcomers, and visitors alike. In Biddeford, developers and city planners worked to convert the town’s historical mills in the town center into mixed-use areas, including housing, recreational spaces, shops, and restaurants with significant success.

Through creative practices like these, rural American towns can build upon their historical roots, embrace prior successes of pre-car development patterns, and reinvent themselves as micro-nodes of walkable, vibrant, and lively communities that foster connection, culture, and sustainability.

Note: This article first appeared in the ENU Newsletter, a newsletter written by Emerging New Urbanist members about topics and debates within the movement. Subscribe to the newsletter.