Citywide forestry plan sets a New Urban standard

Note: CNU and Public Square are closed the week of June 5, following a successful CNU 31 in Charlotte.

Trees are such a ubiquitous part of the urban landscape that their vital role is sometimes overlooked. Nearly every New Urbanist plan makes prominent use of them, and yet the word “tree” does not appear in the Charter of the New Urbanism, observes Jeff Speck, planner and author of Walkable City. Noticed or not, “the humble American street tree might get my vote” for favorite element of walkable cities, Speck writes in his popular 2012 planning book.

It makes sense, then, that Speck led an innovative New Urbanist tree plan—covering the 74 square miles of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. “ReLeaf Cedar Rapids is, to our knowledge, the first time that a thoroughly New Urbanist approach to planning, urban design, and& landscape has been brought to bear on a citywide urban forestry plan,” Speck comments.

It came in the wake of catastrophe. The city of 137,000 people lost two-thirds of its tree canopy in just one hour on August 10, 2021, when a derecho storm swept across Iowa and straight through Cedar Rapids.

The City adopted ReLeaf Cedar Rapids in record time, and began implementation last year, to plant 42,000 street and park trees and advise private landowners on how to replace hundreds of thousands more over the next decade. ReLeaf is a collaboration of the City, nonprofit Trees Forever, landscape architects Confluence, and Speck & Associates.

The City has pledged a million dollars a year, and private funds have also been raised, for a project with long-term payoff for residents. “ReLeaf Cedar Rapids is a visionary plan to build back the 669,000 trees—70 percent of our tree canopy—that was lost. It requires significant investment of resources, but the impact of our efforts will be felt for generations,” reports City Manager Jeff Pomeranz.

Along the way, the plan challenges many of the conventional practices of urban forestry—for example how best to achieve species diversity. “Most New Urban plans include streets and spaces lined by alleés of just one tree species. This makes sense: consistent, repetitive edges help to define space, establish character, and create beauty. A Google search under ‘beautiful tree-lined street’ reveals example after example of utterly uniform alleés. Meanwhile, a superficial understanding of urban forestry would pronounce such a landscape as sacrilege,” Speck says.

Most urban foresters avoid planting two of the same species together to boost resilience to blights like the notorious Dutch Elm disease, which wiped out tree canopies over entire communities. “The result is street after street of tutti-frutti potpourri, where spatial definition is undermined and character lost,” Speck laments.“This was the current standard in Cedar Rapids.”

A deep-dive into the thinking behind this policy—and current research—reveals that diversity is not best pursued on the scale of individual trees and streets, but across neighborhoods and cities, he explains. Diversity should be achieved by mixtures of uniformity, according to the National Arboretum's Frank Santamour, the creator of the influential 10-20-30 Rule (cities should plant no more than 10 percent of any one species, 20 percent of one genus, or 30 percent of one family of tree). In other words, don’t vary species within individual blocks—rather do it across many blocks. “What was perceived to be a conflict between New Urbanism and urban forestry best practices was actually based on a misunderstanding of the latter,” Speck says.

The rethinking comes with a shift in priorities. As Speck describes it, “Unlike many urban forestry plans and much of its practice, ReLeaf Cedar Rapids considers trees in terms of not just their ecological qualities but also their placemaking qualities. Most urban foresters look first at the individual specimen and ask ‘what's best for the tree?’ ReLeaf Cedar Rapids looks first at the parks, squares, and streets of the city and asks ‘what's best for these places.’ ”

Trees are particularly important in the physical definition of urban spaces—and in making walking comfortable and safe. They reduce urban heat islands, absorb pollution and stormwater, calm traffic, and mitigate and adapt to climate change. Trees’ importance to the life and well-being of cities and their inhabitants demands a broader outlook, paying attention to overall place. “It turns out that focusing on trees and focusing on spaces are not contradictory approaches, but the former often undermines the latter, while the latter can quite happily embody the former,” Speck explains.

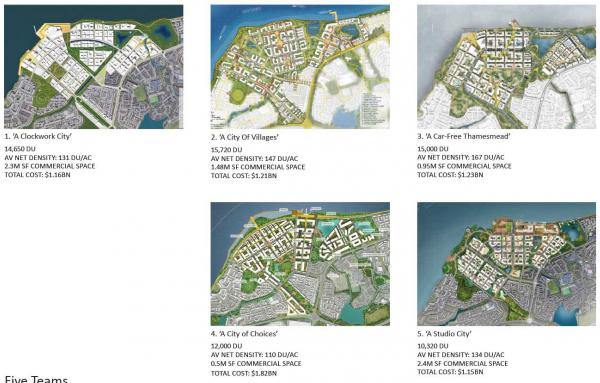

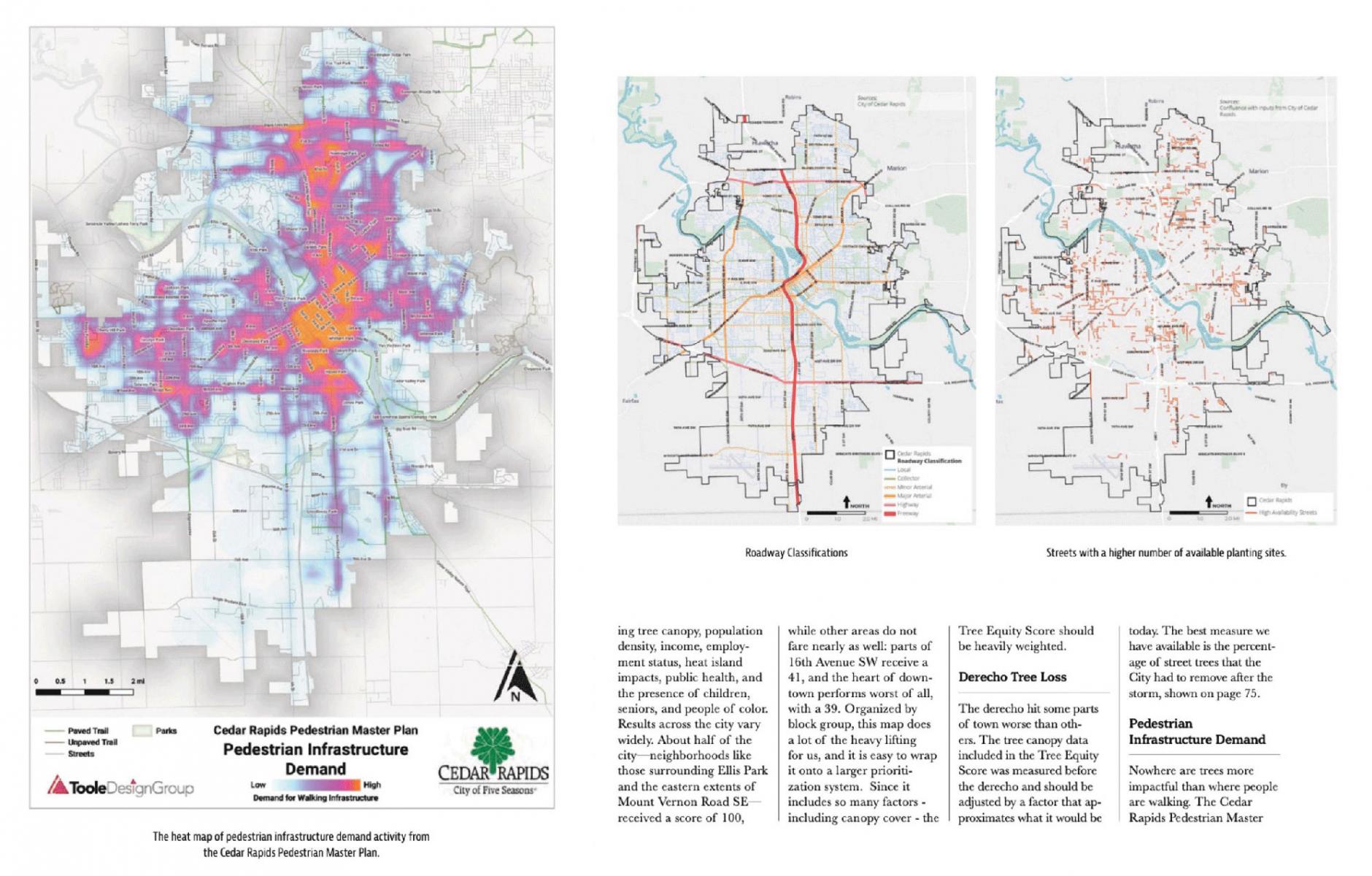

While the entire city needs trees, the order of planting is critical—with important equity implications. The difficult task of prioritizing all street tree replanting over ten years was determined through the community-established “ReLeaf Principles.” Each block of each street was ranked in terms of a weighted average of eight factors: prior canopy, urban heat islands, population density, derecho tree loss, pedestrian infrastructure demand, roadway classification, available planting sites, and—importantly—social vulnerability. The plan “uses tremendous amounts of data and analysis to carefully prioritize replanting in a way that reflects a set of principles defined through the public process, including habitat preservation and equity,” Speck says. Social vulnerability is factored through an Equity Score, created by nonprofit American Forests, that combines neighborhood canopy, income, race, and other characteristics.

ReLeaf Cedar Rapids emphasizes planting trees that grow tall and wide—most of the benefits of trees come from their canopies—and also native species that support the food web and provide habitat for local fauna. The tree list has three categories: Superior, which meet all of the desired characteristics; Allowed, which are big, locally adapted trees that don’t support the food web as well (but may be more available on short notice); and Contingent, which are smaller trees planted only where large trees won’t work, like under transmission wires. The key lessons from the plan are somewhat at odds with standard forestry practice. They are summarized as follows:

- Big Not Small: Don't plant a small-species tree where a large-species tree will thrive. The typical large-species tree provides roughly ten times the ecosystem benefits of the typical small-species tree, yet the planting costs are identical. Henry Arnold (author of the classic Trees in Urban Design) also demonstrates how larger trees are better for tight street spaces, where their broad canopies end up sheltering the space. Small trees clutter narrow street spaces.

- Locals Not Imports: Don't plant a non-native tree where a native tree will thrive. Non-native trees do not support native animals and insects, and can actively undermine the food web. Case in point, Phragmites australis, the common reed, after 500 years in North America, supports only five species of insects. In its native Europe, it supports 170.

- Tots Not Teens:If they can be protected, plant trees when they are very young. Transplanting a tree is a traumatic event that dramatically curtails growth. One-inch caliper trees generally catch up in size with two-inch caliper trees within five years, and then surpass them in growth and vitality. Therefore, particularly with an eye to economy, trees should be planted at the smallest size at which their survival can be ensured.

- Let Trees Mingle: Where possible, plant trees in groups and close together. The misapprehension that trees thrive best when given “space to breathe” is disproved in nearly every forest. Closely-planted trees share nutrients and information through& their roots. More significantly, an intertwined root network makes groups of trees more resilient against windstorms than isolated “sitting ducks.”

Although specific tree recommendations apply only to Cedar Rapids, the principles and general approach could be useful for urban tree planting efforts in other cities, and Speck encourages planners to borrow directly from whatever sections may apply. (Download the plan here.)

Crucially, the plan explains a topic that is all too often ignored or misunderstood: how to use trees to frame streets and squares as outdoor rooms, the Charter Awards jury noted. “This project offers a new lens through which to address urban forestry,” the jury said. “By moving from a one-size-fits-all tree ordinance to a Transect-based approach that addresses a range of contexts, ReLeaf Cedar Rapids is a clear, accessible document that can serve as a model for other municipalities.”

In his recently-reissued update of Walkable City,Speck tells the full story of the Cedar Rapids plan. It is hoped that widespread dissemination of the ReLeaf plan may allow New Urban thinking to positively influence urban forestry, a vital aspect of the built environment.

View ReLeaf Cedar Rapids' Charter Awards ceremony video here.

ReLeaf Cedar Rapids in Cedar Rapids, Iowa

- Speck & Associates, Principal firm

- Confluence, Co-creator and landscape lead

- Trees Forever, Client

- City of Cedar Rapids, Client

2023 Charter Awards Jury

- Megan O’Hara (chair), Principal, Urban Design Associates in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- Andre Brumfield, Principal and Global Director for Cities and Urban Design at Gensler in Chicago, Illinois

- Krupali Uplekar Krusche, Associate Professor, University of Notre Dame School of Architecture in South Bend, Indiana

- Jennifer Settle, urban designer, architect, and Senior Associate with Opticos Design in Chicago, Illinois

- Patrick Siegman, transportation planner, economist, and Principal of Siegman & Associates in San Francisco, California