New Urbanism and its influences in the Charlotte region

Note: CNU and Public Square are closed the week of June 5, following a successful CNU 31 in Charlotte.

Something was in the air or water in Charlotte in the 1990s, or maybe it was moonshine from the North Carolina hills. But Charlotte was an early adopter of New Urbanism—much more so than most cities. Many planners and developers were willing to try a new approach, and they led by example—especially in reforming codes.

Some of the nation’s first municipal form-based codes—called traditional neighborhood development codes at the time—were adopted in Charlotte suburbs nearly three decades ago. Belmont in Gaston County was the first, followed by Davidson, Huntersville, and Cornelius and Mecklenburg County.

New urbanist developments followed—in those and other towns around the region. By the mid-to-late 1990s, Charlotte was surrounded on all sides by new urbanist planning efforts. “The DNA changed,” explained architect and urban designer Tom Low, who has been living and working and promoting New Urbanism in the Charlotte area for three decades. “It’s had a good overall ripple effect. A lot of development follows at least some new urbanist principles as a result.”

The city center, Uptown, began to revive in the 1990s. And, public housing projects were redesigned as neighborhoods in the First Ward and the West Side, with the help of new urbanist architects. The first glimmers of redevelopment of funky warehouse districts, like the South End, also began to emerge. In the decade after the city opened its light rail system in 2007, these efforts began to take off.

To be sure, Charlotte has sprawled, too—as much as nearly any fast-growing US metropolis. The city is the center of a huge economic engine. New Urbanism was a niche within a larger sprawl machine. But at least there was a choice—a mixed-use, walkable, compact development philosophy was taking root. You can see the considerable results of those green roots at CNU 31 in Charlotte next week (in addition to the first Strong Towns National Gathering).

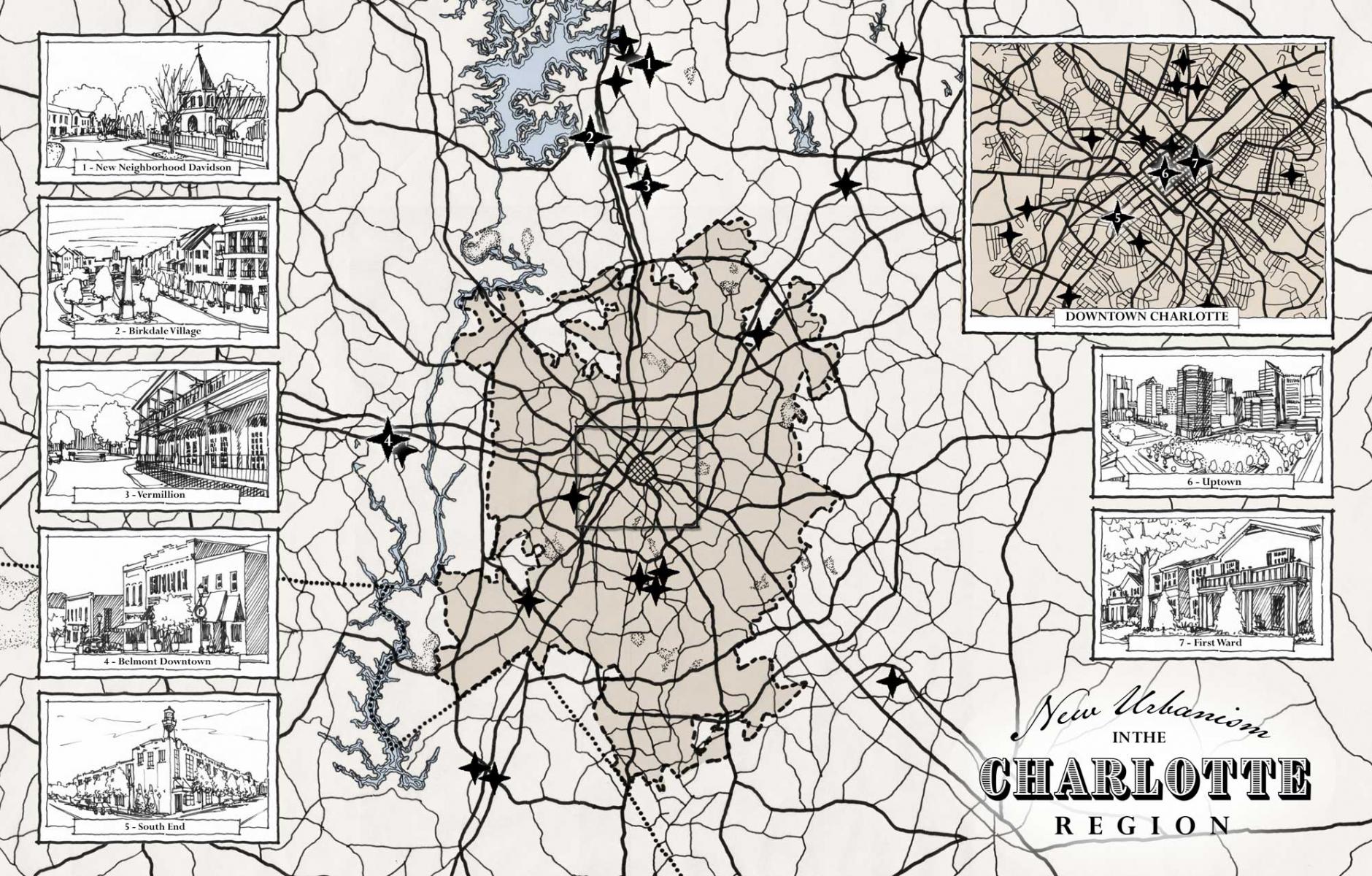

In honor of that event, and the tremendous efforts of new urbanist planners over the last 30 years, we have created a Google map of “New Urbanism and its Influences in the Charlotte region.” The influences go both ways. New Urbanism has influenced the region, and vice-versa. See the map imbedded below, and click around to get more details on the various locations. (At the top of this article, a beautiful hand-drawn version of that map was created by Naomi Leeman.) Listed below are 24 neighborhood-scale new urbanist projects in and around Charlotte—nearly all of them complete.

Eight redevelopment areas—pre-existing neighborhoods that have been substantially transformed with the help of new urbanist planning—are also listed. Three historic models are identified—neighborhoods that have been especially influential to new urbanist planners. Some of these areas probably qualify for more than one category, but I listed them where I think they best fit. Finally, the planning reform continues to this day. As examples, three CNU Legacy Projects—new urbanist planners held charrettes recently to have an impact on the host region ahead of the annual Congress—are also included.

Those who attend the Congress, or visit Charlotte for any reason, can use the map as a guide.

In Charlotte, everything will be lush and green for CNU 31—but that is not unusual. Greenery is an important and prominent aspect of the urban environment, exemplified by the city’s historic greenways, and visible in the early traditional neighborhood developments—where the trees have grown up to full size, Low says. In the First Ward, adjacent to downtown and within walking distance to the Congress, is one of the nation’s best public housing redevelopments. It is good, in large part, because of the trees, Low says. “The trees here are a major part of the urban environment. It feels really green here,” he says. “One take away from Charlotte is how important a tree canopy is.” (For more on that subject, see the recent article on the urban forestry plan for Cedar Rapids, Iowa).

New Urbanism on a neighborhood (or larger) scale in the Charlotte region

- Afton Village. This traditional neighborhood development in Concord, NC, is the personal vision of David Mayfield, a developer who was trained as an architect, landscape architect, and engineer. Afton Village employs the concepts of New Urbanism and includes useful services and businesses, such as a YMCA, shops, restaurants, and a bakery, in the village center. A new greenway connects the village to other destinations.

- Apex. Apex is a mixed-use infill development in the SouthPark area of Charlotte. Originally built as an "edge city" around a large shopping mall, the area is densifying and becoming more urban through infill like Apex.

- Arbor Glen. This HOPE VI public housing redevelopment of the former Dalton Village project is an example of new urban public housing design, which advocated for neighborhoods that take design cues from best historic places in a city.

- Ayrsley. This town center and traditional neighborhood development in south Charlotte was the largest and densest new urban plan of its kind in the Charlotte region when it broke ground in 2002. More than a million square feet of commercial space, mixed with homes ranging from single-family to apartments, were built on a neighborhood scale in Ayrsley, challenging prevailing development practices.

- Baxter Village. This major traditional neighborhood development is one of the earliest in the Charlotte region, helping to establish a new pattern of growth in suburban Fort Mill, South Carolina.

- Beatty Street infill. Multiple infill developments in the historic Town of Davidson around the turn of the millennium demonstrated the viability of a range of walkable housing types, public spaces, and civic buildings including a school. These developments showed builders that compact housing, with rear lanes, in a walkable format on infill sites, is marketable. The projects were aided by an early new urbanist code, written in 1995.

- Birkdale Village. Opened in 2003, Birkdale Village is a town center and traditional neighborhood development in Huntersville, NC, that has become a national model for how to build mixed-use. The development repudiated the standard retail designs of 20 years ago, and has continue to be successful. A major expansion of Birkdale Village is now planned, two decades after it was built.

- Brightwalk. A new community on the former Double Oaks development, the 98-acre neighborhood includes single family homes, townhomes, and apartments with trails, shops, offices, and restaurants. In this reimagining of the neighborhood design, Brightwalk also features a center for art and innovation.

- Camp North End. Camp North End is the reimagining of a 76-acre site that was a Ford plant from the 1920s, and then a WW2 Army depot, as a business and event district with a funky industrial vibe. Camp North End is located about a mile north of Uptown, near several older neighborhoods. It offers a unique urban experience in Charlotte.

- Cornelius center. This new town center with civic buildings and residential construction has added life to the heart of Cornelius, a northern suburb, based on design work by DPZ and Shook Kelley.

- Davidson Rural Area Plan. The town of Davidson adopted a plan and form-based code to protect 65 percent of its rural land over six square miles, and focus compact development in traditional neighborhoods. The plan was adopted in the spring of 2017, a policy that will save a minimum of 2,463 acres of permanently protected, publicly accessible open space as the sector is built out. The plan won a CNU Charter Award in 2018.

- First Ward. The First Ward is a quadrant of Charlotte's center highlighted by one of the city's most prominent HOPE VI redevelopments, setting a new standard for public housing close to the city's central business district.

- Gateway Village. This transit-oriented, mixed-use urban center is part of the explosive growth along Charlotte's Gold Line light rail corridor. High-density, mixed-use nodes along new rail lines are transforming and enlivening Charlotte's urban fabric served by transit.

- Kingsley Town Center. Kingsley is a mixed-use development well under construction that is planned for two large corporate headquarters, two hotels, multi-family over retail, a lake and amphitheater and 150,000 square feet of small shops and restaurants. The design pays homage to Fort Mill's textile history.

- Lake Park. Lake Park was designed as a neotraditional neighborhood and incorporated as a municipality in 1994, early in its buildout. The village was way ahead of its time in combining self-governance with many elements of traditional neighborhood design, including a mixed-use town center, shared public spaces, and a more compact network of streets and residential types. The village now has more than 3,000 residents, and civic and industrial uses.

- Locust Town Center. This traditional neighborhood development, including a small town center and adjacent neighborhood, connects to a historic hamlet. This hamlet extension argues for the versatility of TND—that it can be built in a range of place types.

- Montieth. This early traditional neighborhood development in Huntersville demonstrated compact development on internally connected small blocks and a variety of building types. The frontages of the houses focus on walkability—unlike conventional suburban development of the time.

- New Neighborhood in Old Davidson. Now more commonly known as St. Alban's, this neighborhood is an extension of the historic town of Davidson. About 70 acres in size, New Neighborhood in Old Davidson was an ambitious challenge to conventional development practices, creating a more sustainable model for growth in the northern Charlotte suburbs. The project was aided by an early new urbanist code, written in 1995.

- Park at Oaklawn. This redevelopment of former Fairview Homes built a neighborhood with a mix of housing types. Charlotte received multiple HOPE VI grants in the 1990s and early 2000s, helping to change the face of public housing in the city.

- Piedmont Town Center. Piedmont Town Center created four blocks of mixed-use urbanism grouped around a roundabout within the SouthPark area of Charlotte. The town center is part of an ongoing urban infill transformation of SouthPark, an "edge city" that is centered on a mall.

- Sharon Square and Phillips Place. Sharon Square and Phillips Place are two connecting mixed-use town center developments in the "edge city" of SouthPark in Charlotte. They form part of the SouthPark loop, including several infill projects that are contributing to an ongoing retrofit of the SouthPark area from suburban to urban.

- Stowe Manor Village. This 15--acre infill village introduced new urban neighborhood scale development with a mix of housing types, including live-work, around an historic manor house. The development is walkable to, and helps support, Belmont's revitalized downtown.

- Vermillion. This traditional neighborhood development in Huntersville, NC, changed the conversation on development in the Charlotte region. Developer Nate Bowman used revived building types, such as live-work townhouses, in new forms, to build a sense of place in the suburbs. Vermillion was aided by an early new urbanist code, written in 1996.

- Waverly. This 90-acre, intensive, mixed-use and pedestrian-friendly development sets a new pattern for retail, workplace, and residential on the south side of Charlotte.

Redevelopment areas

- Belmont downtown. Leaders in Belmont adopted the state's first public new urbanist zoning code in 1994. This was after The Belmont redevelopment plan was written by Duany Plater-Zyberk, recommending code reform. The code, written by city planners, and subsequent traffic calming set the stage for the revitalization of downtown that continues today.

- Fourth Ward. Residents rejected plans to tear down historic blocks for modern towers, preserving some houses in the Fourth Ward in the latter decades of the 20th Century. Instead, new low-rise development was built around this homes, establishing a desirable neighborhood adjacent to the central business district.

- Kannapolis downtown. This revitalization and renewal of a former company textile mill town is a powerful statement of how a community can reinvent itself. After 6,000 workers were laid off in 2003, the town reimagined itself as a research and development center and corporate headquarters locale. As part of that revitalization, the town built a sense of place with brick downtown architecture and public realm, showing the role that urban design can play in a town's future. New traditional buildings extended the historic main street.

- LoSo. The Lower South End is an emerging transit-oriented development, infill, mixed-use district along the Blue Line light rail in Charlotte.

- NoDa. This arts and entertainment district northeast of Charlotte's central business district has emerged as a cool destination in the city. Substantial residential and mixed-use development has taken place in this former warehouse district, affirming that urban places with character can have multiple lives, nourishing economic and social activity over multiple generations.

- Plaza Midwood. Plaza Midwood was first established in 1910 as a streetcar suburb of Charlotte, and has this century experienced significant investment and business and residential development. Now one of Charlotte's most diverse and eclectic neighborhoods, Plaza Midwood is filled with art galleries, funky stores, and restaurants. A planned expansion of the Gold Line would bring light rail to Plaza Midwood.

- South End. Architect Kevin Kelley and developer Tony Pressley coined the name for this former warehouse district, Charlotte's answer to places like SoHo, in 1996. Redevelopment started slowly, until the Lynx Blue Line light rail was planned and built in 2007. Intensive development has turned this formerly abandoned area to a lively mix of residents and major employers like Allstate Corp., Ernst & Young and Lowe’s. Expected to have 17,000 residents by next year, the South End has four stations on the Blue line.

- Uptown. Charlotte's central business district, also known as "Center City," has undertaken a transformation with banking industry money and investment in light rail. Uptown is a massive employer, with 33 million square feet of office space. Museums, theaters, hotels, high-density residential developments, restaurants, and bars are heavily concentrated there, with over 245 restaurants and 50 nightspots, according to Wikipedia.

Historic models

- Dilworth. The first transit-oriented development in Charlotte, Dilworth was launched by the industrialist and developer Edward Dilworth Latta in the 1890s on 250 acres of land, then outside of the city limits. The neighborhood was connected to the first streetcar line extending south from downtown, ending at an amusement park: Latta Park. Latta used the same block size and orientation as had been established in the city core area, but the layout was modified with more curvilinear patterns by the Olmsted Brothers during buildout in the 20th Century.

- Myers Park. This neighborhood designed by John Nolen in the early 20th Century is a classic town plan that was inspirational—especially in its use of landscape elements and tree canopy.

- Wesley Heights. Wesley Heights is a "streetcar suburb" of Charlotte, now a registered historic neighborhood of bungalows from the 1920s. Wesley Heights is a neighborhood worthy of inspiration and precedent for new urban planning and development.

Legacy Projects

- Healthy Highland. Building on a successful nonprofit food kitchen, the Highland neighborhood in Gastonia, North Carolina, is planning to grow in a healthy and walkable way, even as gentrification pressure mounts. In advance of CNU 31, planners and citizens recommended mixed-use plans that will better utilize vacant parcels in the largely African-American neighborhood northwest of downtown Gastonia.

- University City. The redevelopment of a shopping center into a university-oriented mixed-use community is envisioned to transform an "edge city" in Charlotte. The plan drawn in advance of CNU 31 aims to build a transit-oriented college town for the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, a major research university.

- West Boulevard. Planners and citizens created designs and implementation policies to transform a corridor serving low-to-moderate income families. The plans made in advance of CNU 31 promote a community led revitalization that benefits existing residents, provides healthy foods and economic development, and humanizes an automobile-centric thoroughfare.

Note: Tom Low was very helpful in putting together this map, notably an earlier map that he drew identifying where many of these projects are located.