Theorizing the rural-urban transect

"What matters in a building or town is not its outward shape, its physical geometry alone, but the events that happen there"

—Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building 1979

Two Ethics of Research

Urban planning paradigms are influenced by two prevailing ethics: utilitarianism and deontologism. Utilitarian urban studies views urban agglomeration as the outcome of economic exchange, where seemingly uncoordinated micro-social activities give rise to organized macro-social structures (Abbott, 2004). Urban theorists examine the connections between socio-economic institutions and the emergence of cities as geo-historical or spatial-temporal arrangements. Simply put, urban sociology is the study of invisible hands. Bookchin writes: “City planning, however, is an expression of mistrust in the spontaneity of contemporary social relations,” (1992). The deontological ethic advocates therapeutic interventions in economic activity to address issues such as a dangerous amount of density, as seen in overcrowded industrial cities. These ethical perspectives lay the groundwork for exploring concepts like use-based zoning and form-based codes, which define the organization of urban space and shape the built environment. Talen notes at CNU.23 there are two historical thrusts of urban development: what occurred before the industrial revolution and what occurred after. The latter tradition is dedicated to “reforming something that turned awful,” (2015).

Two Paradigms of Land Usage

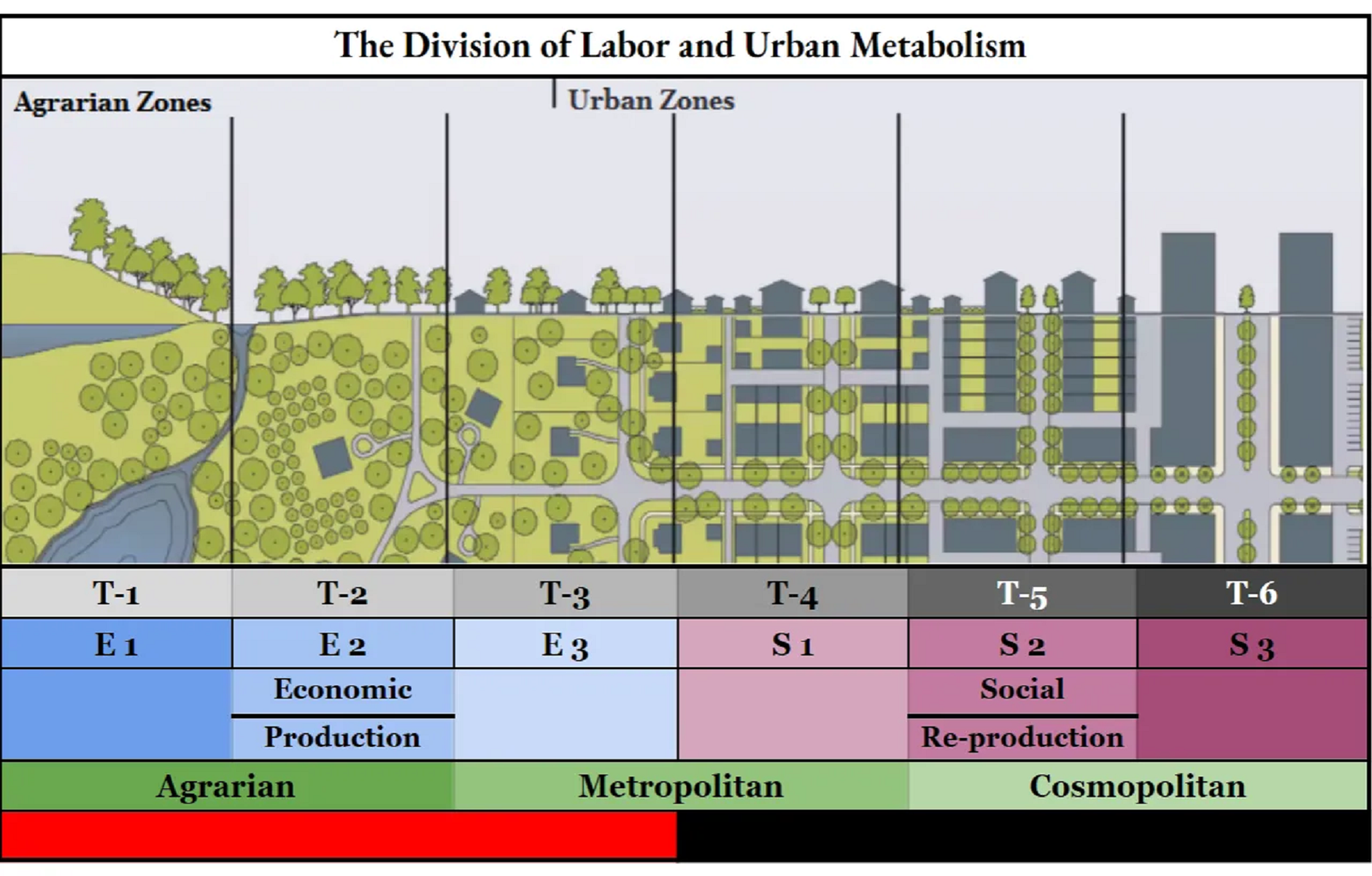

Two prevailing paradigms of land usage in urban planning are euclidean use-based zoning and form-based coding. Use-based zoning segregates city functions into single-use enclaves, while form-based coding embraces social diversity and designs a predictable public realm. The rural-to-urban transect, central to the New Urbanism movement, organizes various form-based codes along a gradient from rural to urban areas. This transect can be conceptualized as different zones of intensity, ranging from natural and agrarian to urban centers and cores. While form-based coding is certainly preferable, the false dichotomy between form and function needs to be overcome. This can be achieved by synthesizing the paradigms under the sociological concept of metabolism.

Metabolism: Unifying Form and Function

Metabolism offers a conceptual framework that unifies form and function under motion. Just as a living organism's organelles contribute to its overall function, urban spaces are shaped by the interplay of various elements. Christopher Alexander describes towns as living entities with patterns of action and space (1979). However, within the discourse of New Urbanism, there is a tendency to view individuals primarily as consumers rather than active participants in economic life. This is evident in the overrepresentation of typologies which promote retreats, resorts, and natural preserves as an escape from economic activity. To truly understand urbanism, it is crucial to recognize the intimate connection between economic life and the built environment.

The Transect and the Division of Labor

The rural-urban transect, with its different zones, represents not only physical environments but also distinct social structures. The transect can be seen as representing the types of social structures found in rural and urban areas. Additionally, metabolism, or stoffwechsel, provides a lens for understanding how raw materials are transformed through human labor during economic exchange. Each T-zone within the transect represents a snapshot of the stock and its contextual geography, moving along its life course from production to consumption.

The diversity of industries and their spatial agglomerations is co-constituted by the emergent division of labor within society, shaping the interconnectedness of town and country.

Reconsidering the Special District (SD)

T-zones 1, 2, and 3 are where economic production happens, while T-zones 4, 5, 6, and SD focus on social reproduction– E1, E2, E3 and S1, S2, S3. T; 1, 2, 3 are the realm of economic production and T; 4, 5, 6, SD are the realm of social re-production. Contra Talen (2008), the New Urbanists should not advocate for strengthened economic cores. The most valuable geography should be prioritized for social uses. Concentrating economic growth in high-density areas leads to migrations from rural to urban regions, causing a disruption in agrarian economies known as a metabolic rift (Foster, 1999). Prioritizing high-density areas for care work is an act of care itself, as it helps limit the size of urban agglomerations. S3 acknowledges SD as an anomaly within the diverse agrarian-urban transect. An economic T6 represents an agglomeration economy, while a social T6 signifies the pinnacle of social reproduction. S3 involves the production of people—a campus-like environment with schools and hospitals. New Urbanists should embrace the idea of locating factories amidst fields, and SD can be seen as a single-use district within the transect.

Conclusion

Urban planning paradigms rooted in opposed ethics can be synthesized under the sociological concept of metabolism where form and process are unified as motion. By embracing this perspective, we can design urban environments that prioritize economic vitality, social re-production, and sustainable smallholder development. The metabolism framework for understanding the rural-to-urban transect illuminates the invisible hand that organizes urban densification and agglomeration. Through the synthesis of these concepts, we can create vibrant and inclusive communities that harmonize form, function, and human flourishing.

References:

Abbott, Andrew. Methods of Discovery: Heuristics for the Social Sciences. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2004.

Alexander, Christopher. “The Genetic Power of Language.” Essay. In The Timeless Way of Building, 355–56. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Bookchin, Murray. 1992. Urbanization Without Cities : the Rise and Decline of Citizenship. Montréal ;: Black Rose Books.

Foster, John Bellamy. “Marx's Theory of Metabolic Rift: Classical Foundations for Environmental Sociology.” American Journal of Sociology 105, no. 2 (1999): 366–405. https://doi.org/10.1086/210315.

Talen, Emily. “Beyond the Front Porch: Regionalist Ideals in the New Urbanist Movement.” Journal of Planning History 7, no. 1 (2008): 20–47.

Talen, Emily. “The Industrial Revolution” In New Urbanism 101: The History of Planning. CNU 23. Dallas-Fort Worth, 2015.

Note: This article first appeared in the ENU Newsletter, a newsletter written by Emerging New Urbanist members about topics and debates within the movement. Subscribe to the newsletter.